Ancient human groups working on the outskirts of Rome butchered a straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon) with very small stone implements and then shaped some of its bones into larger tools, according to research published on Oct. 8 in the open-access journal PLOS One by Beniamino Mecozzi and colleagues at Sapienza University of Rome.

The team reports a toolset dominated by small flakes measuring roughly 5–30 millimeters, whose use-wear indicates work on soft tissues.

They add that the near-absence of cut marks fits with butchery carried out using such small implements, which tend to leave fewer marks on bone, and that at least two elephant bones were knapped into formal tools.

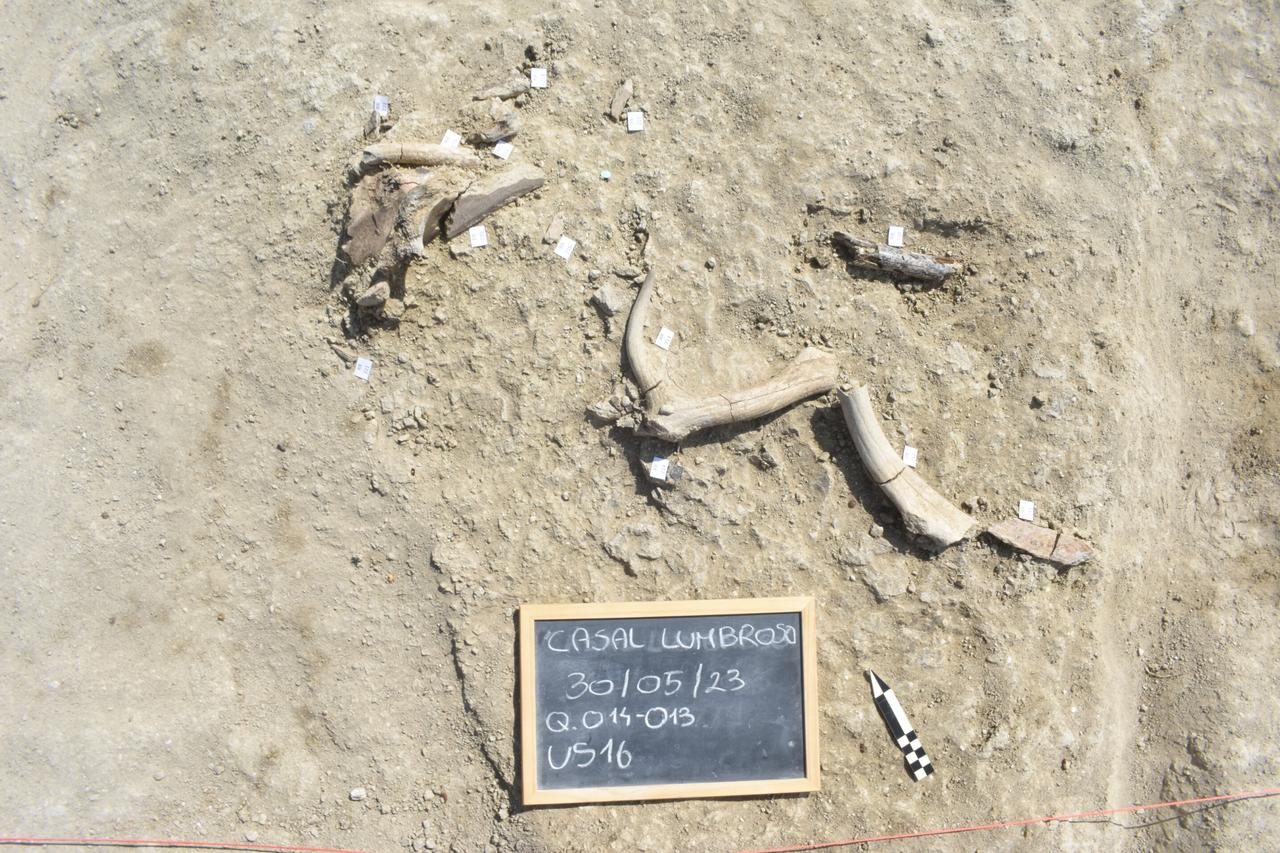

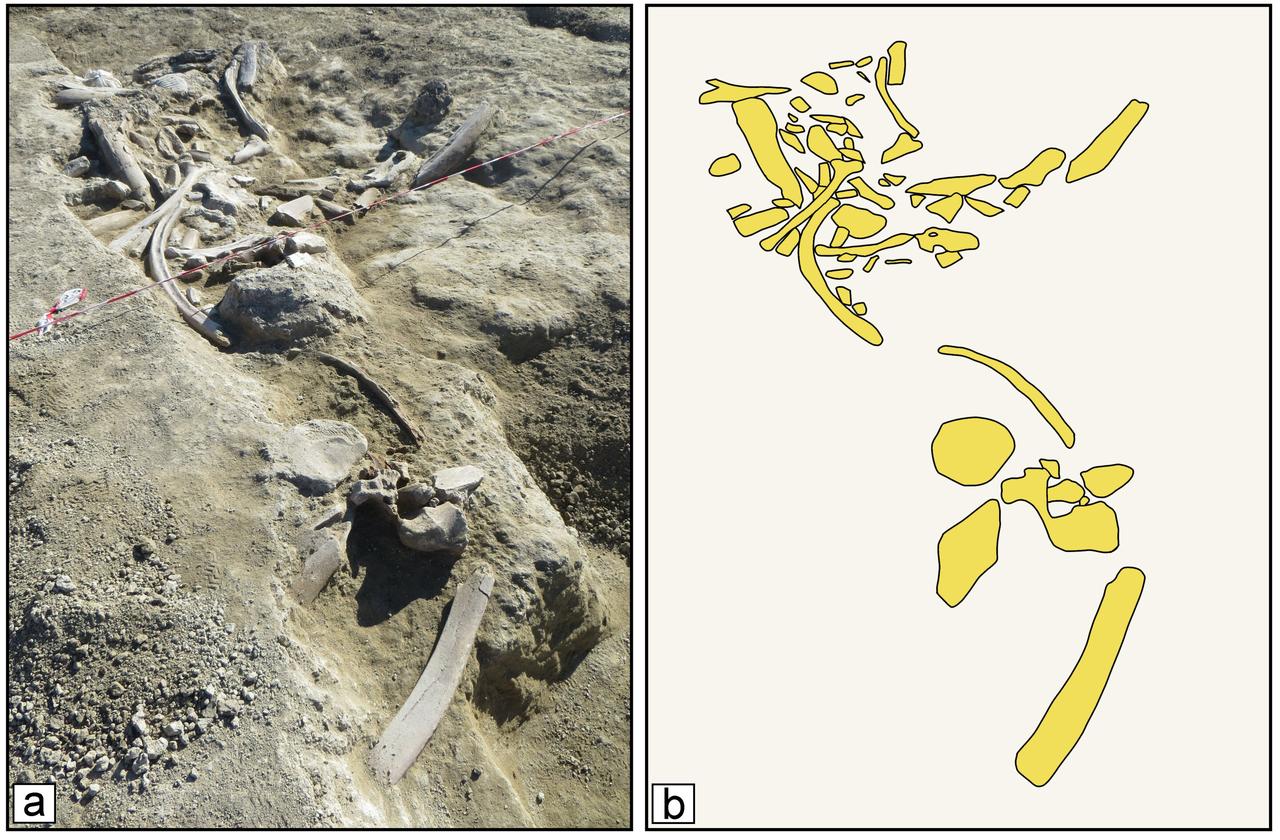

Excavations at Casal Lumbroso yielded remains from a single straight-tusked elephant—listed as 341 identified specimens—alongside more than 500 stone artifacts, including flakes, cores, one handaxe and numerous chunks/fragments.

Several bones display fresh fractures and impact marks, consistent with deliberate breakage shortly after death, and some were further modified for use.

Dating places the site at about 404,000 years ago during an unusually warm interglacial phase of the Middle Pleistocene, when conditions would have favored repeated human use of the landscape.

Researchers link Casal Lumbroso to a broader pattern seen at several central Italian sites, where small-pebble lithics, bone tools and butchered pachyderm remains turn up together.

They argue this reflects a consistent strategy in mild-climate intervals: exploit large carcasses fully for meat and marrow, then carry on by reworking bones into durable tools.

The authors sum up the findings this way: “Our study shows how, 400,000 years ago in the area of Rome, human groups were able to exploit an extraordinary resource like the elephant—not only for food, but also by transforming its bones into tools.”