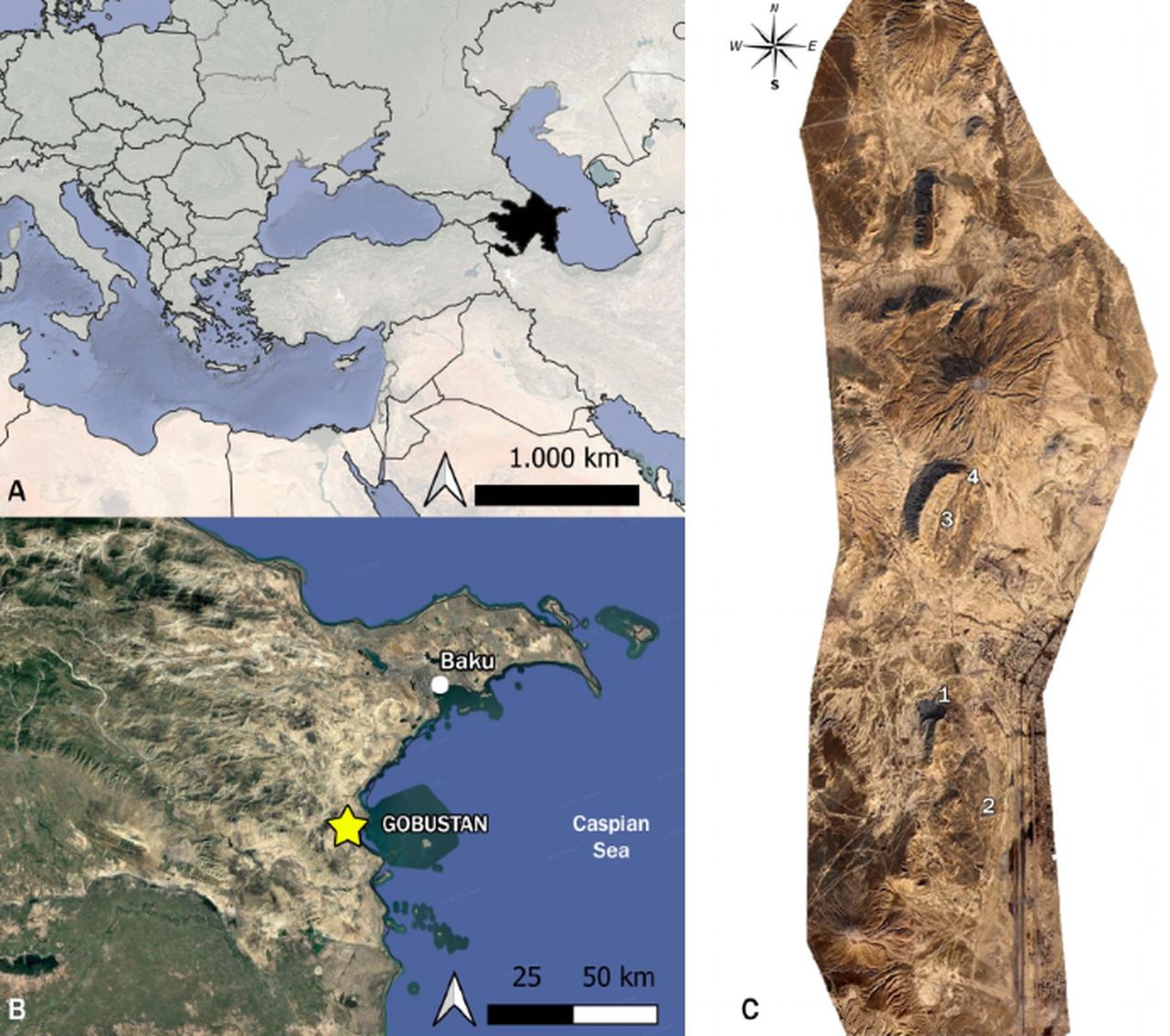

An expansive new study published in Alpine and Mediterranean Quaternary has spotlighted the Gobustan region of Azerbaijan as a key archaeological site connecting prehistoric Europe and Central Asia.

Located on the western shores of the Caspian Sea and declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2007, Gobustan holds over 7,000 rock engravings—or petroglyphs—on more than 1,000 rock surfaces. These engravings stretch chronologically from the Upper Palaeolithic period through the Middle Ages, covering a vast span of human history and cultural evolution.

Gobustan lies within a semi-arid environment shaped by desert conditions and ancient shifts in the Caspian Sea’s levels. The two main hills, Boyukdas and Kicikdas, once emerged as islands during periods of high sea levels approximately 14,000 to 12,000 years ago. These geological changes influenced not only settlement patterns but also the positioning and themes of the rock art.

Vegetation adapted to arid climates and marine fossils embedded in limestone point to repeated submersion by the Caspian Sea. These environmental dynamics played a role in shaping the human experiences and symbolic expressions recorded in the region’s rock art.

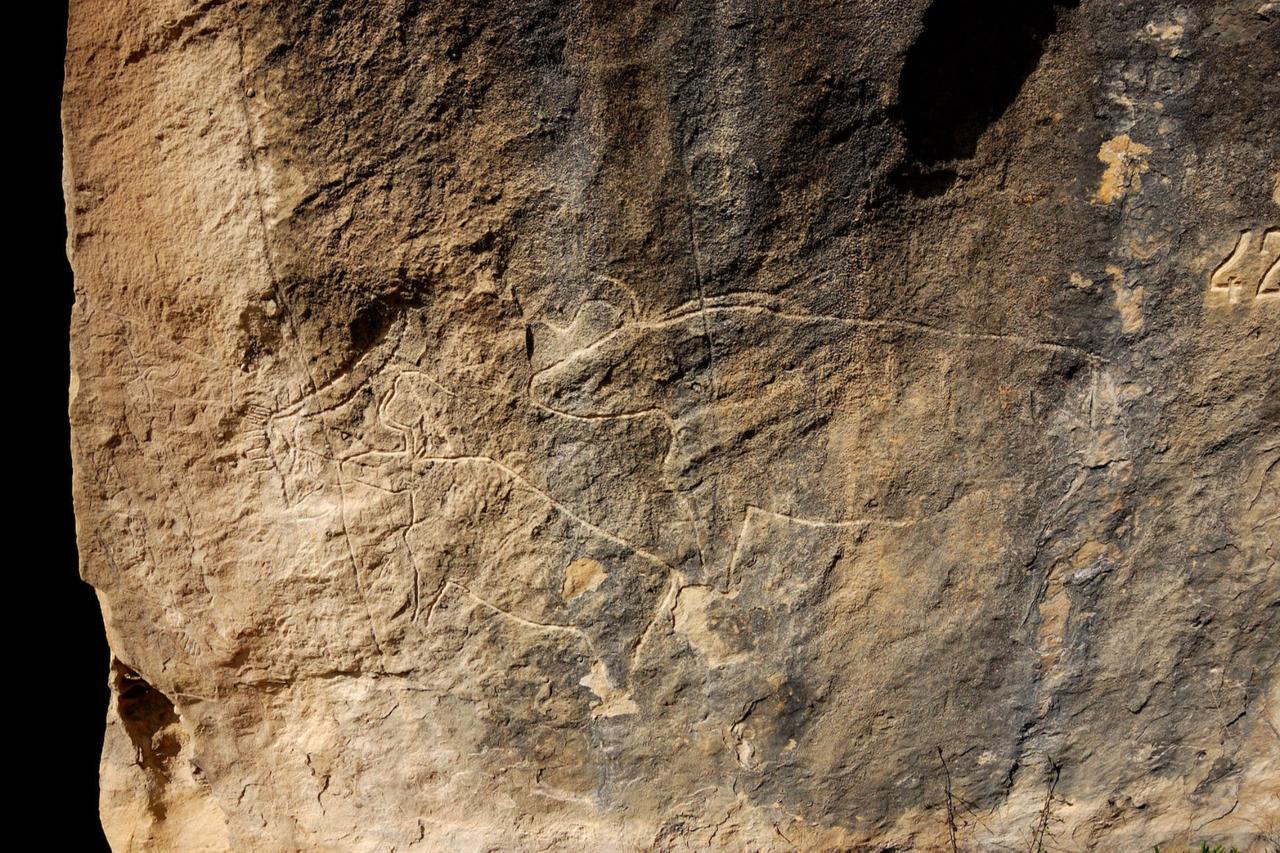

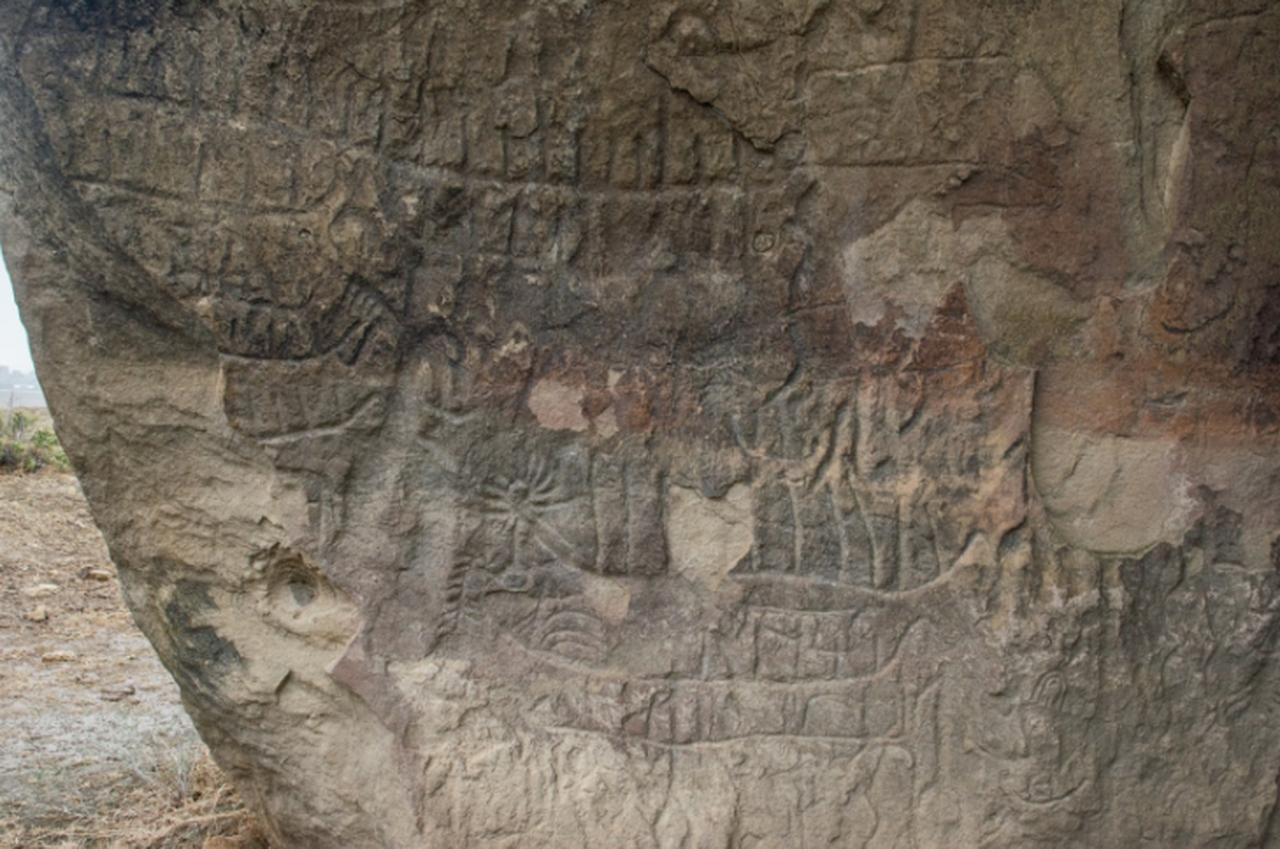

The petroglyphs at Gobustan go far beyond simple depictions. They include representations of animals—such as aurochs, ibex, deer, and camels—as well as boats, human figures, and abstract signs known as tamgas, which were used historically for identifying livestock. Boats, in particular, feature prominently and are thought to reflect early seafaring practices and religious symbolism.

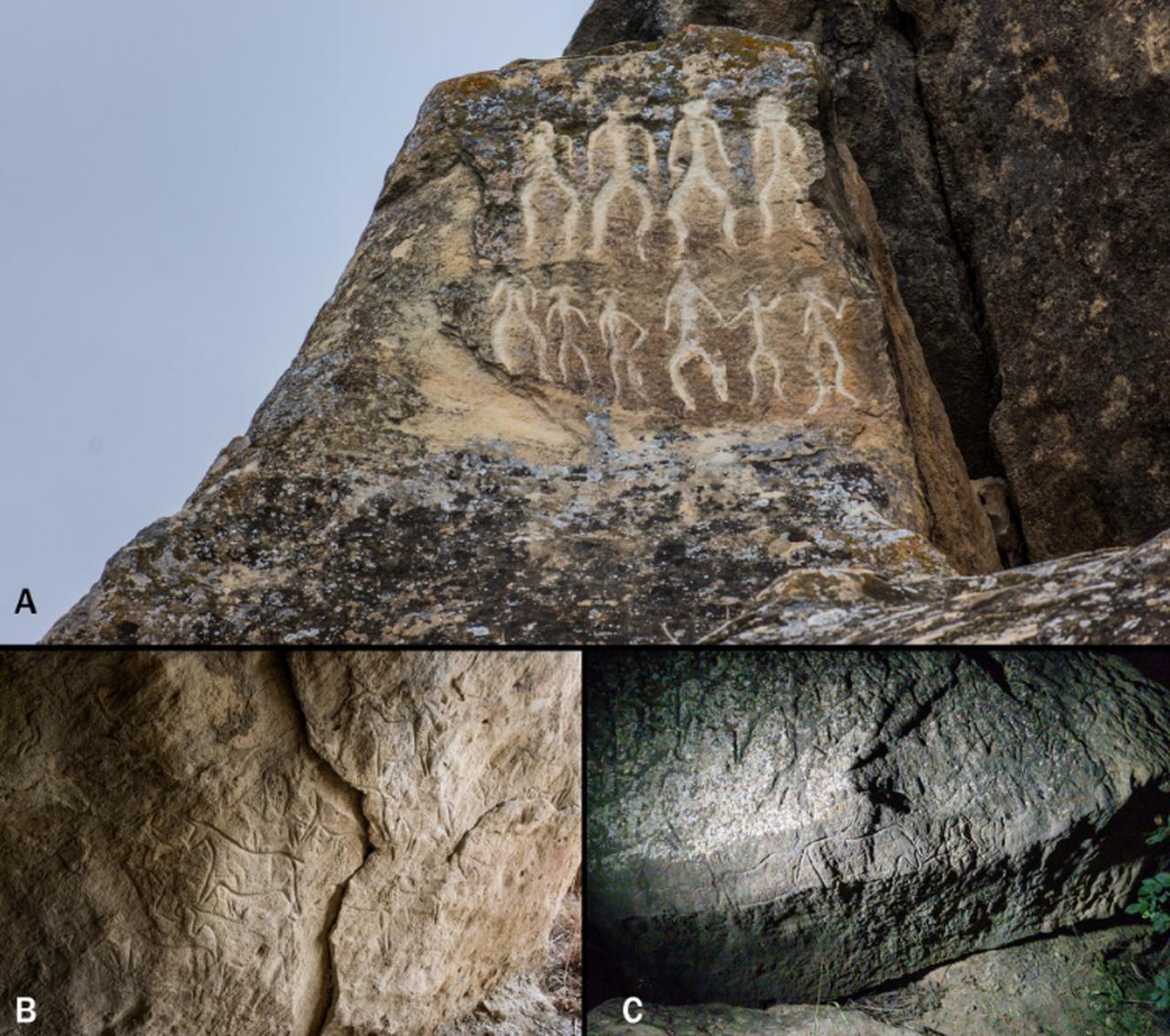

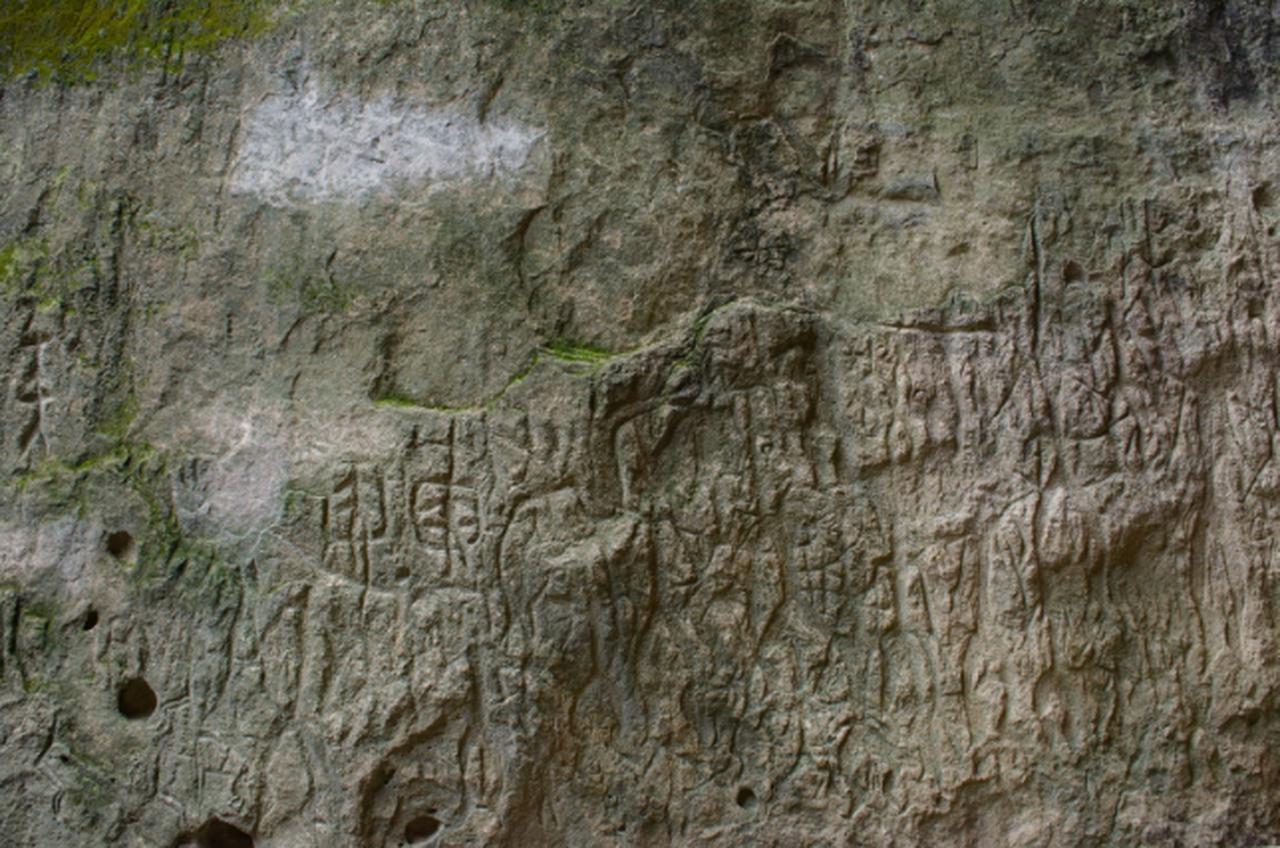

Each image was carved into limestone using thick, deep outlines, and many overlap older figures, suggesting long-term reuse of symbolic space. These layers form visual “palimpsests” that point to enduring cultural continuity over thousands of years.

Archaeological excavations have revealed tools, burials, and domestic remains across various rock shelters. Early inhabitants were hunter-gatherers focusing on gazelle and mule populations. Later periods saw the rise of pastoral societies and more complex economies, marked by artistic changes in rock depictions.

The Bronze Age introduced new motifs, especially of ibex and deer, reflecting changes in religious beliefs and economic life. These animals gradually became central figures in local cosmologies and were often linked to fertility or sun worship.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Gobustan’s rock art is the depiction of boats. Simple longboats carved into high terraces appear to date back over 14,000 years, during the deglaciation period when the Caspian Sea’s level was at its peak. Later depictions show more stylized vessels, some featuring sun symbols and X-shaped crew formations. These changes in design possibly mirror shifts in ideology and culture.

The rock engravings offer valuable insights into how ancient people understood their surroundings—not just as physical spaces but as spiritual landscapes or “seascapes” intricately linked to daily survival and metaphysical belief.

Among the anthropomorphic images, female silhouettes stand out as particularly significant. Ranging from stylized to naturalistic, these figures are sometimes placed in isolated or hidden rock formations, such as the “Seven Beauties” on Rock No. 78. The exclusive placement of these figures implies possible ritual significance and suggests that certain spaces were used for specific social or spiritual functions.

Additionally, some rock shelters such as Firuz contain burial sites, underlining the connection between rock art and ritual activities related to the afterlife.

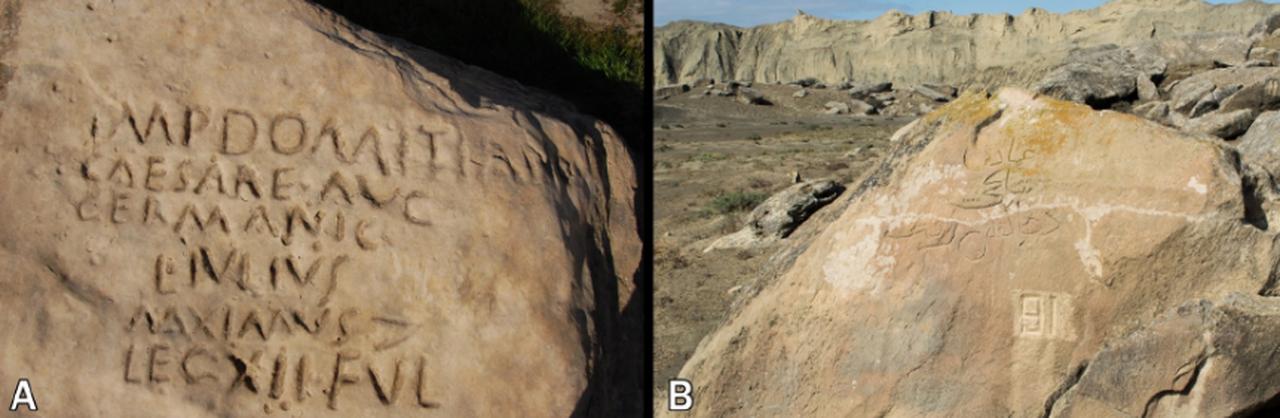

Gobustan also preserves written records. One of the most remarkable is a Latin inscription left by a Roman centurion of the Legio XII Fulminata—believed to be the easternmost Roman epigraph ever discovered. Other inscriptions, such as one stating “Imad Shaki came, prayed, left,” written in Arabic script, reflect religious pilgrimages in the 13th and 14th centuries.

These writings underscore Gobustan’s role as a historical bridge between Europe and Asia, visited by diverse peoples over millennia.

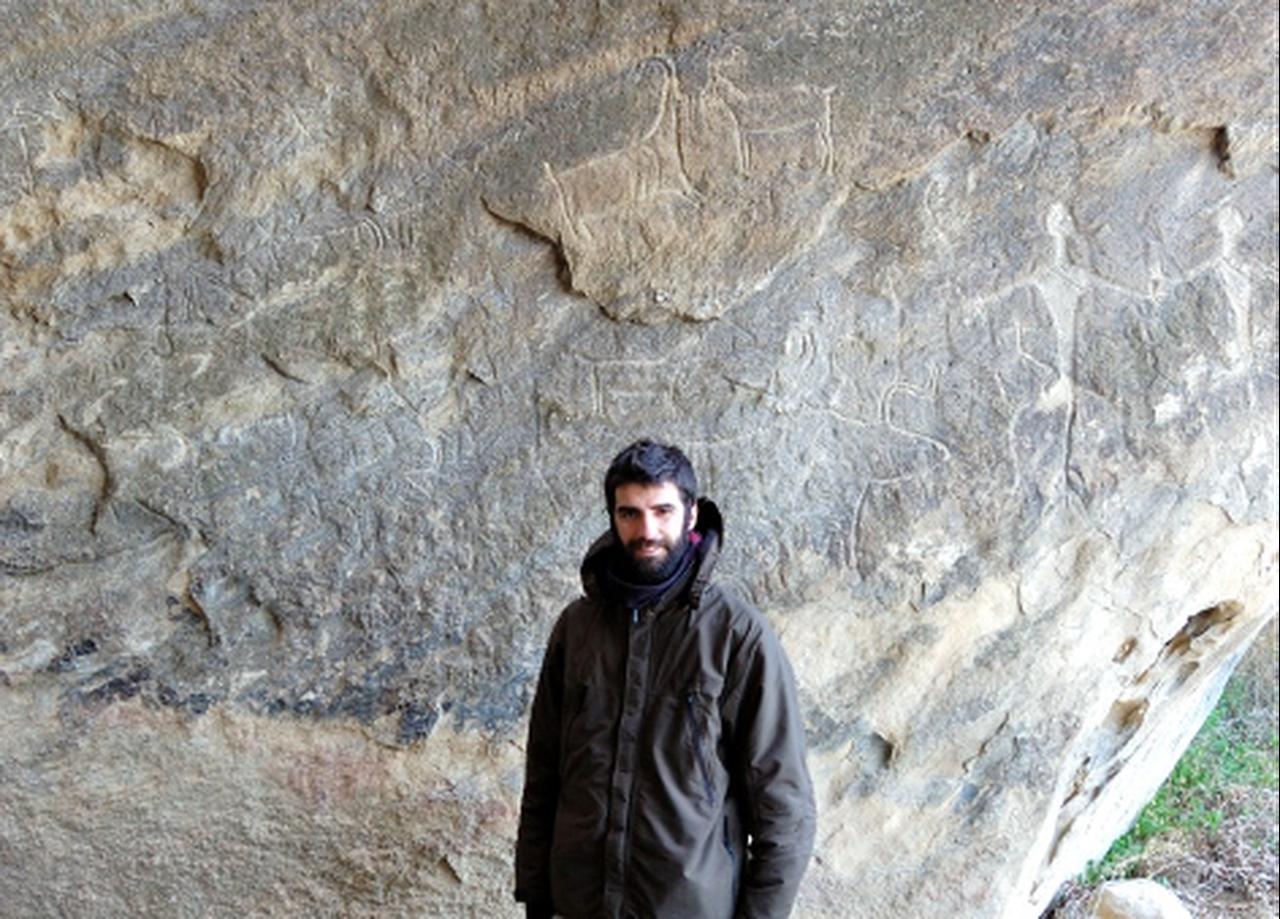

In 2019, a new interdisciplinary research project—funded by Fundacion Palarq-Fundacion Atapuerca and the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs—began focusing on the Ana Zaga shelter, a densely decorated rock shelter on the upper terrace of Boyukdas. With fieldwork resuming in 2021, the team aims to uncover how daily life, symbolic expression, and environmental change intersected at this site.

By combining archaeological excavation with stylistic analysis and environmental studies, the project seeks to clarify how the Gobustan rock art fits within the broader framework of Eurasian prehistoric culture.

Gobustan’s engravings are not just archaeological artefacts—they are powerful records of human thought, spirituality, and connectivity. Through the lines etched in stone, researchers are uncovering how early societies made sense of their world, exchanged ideas, and expressed shared values across vast distances.