Since the early days of exploration in the Near East, archaeology has been wrapped in tales of danger, discovery, and adventure. From the romanticized writings of early explorers like Austen Henry Layard to Hollywood’s portrayal of intrepid diggers unearthing lost relics, the discipline has long captured the public imagination.

Yet, while modern archaeologists work with precision and scientific rigor, cinema continues to depict the field as a quest for glory and ancient power.

The most iconic cinematic archaeologist, Indiana Jones, embodies the public’s fascination with adventure and intellect. Dressed in his fedora and armed with a whip, he bridges the worlds of academia and action.

But as scholar Kevin McGeough explains, film archaeologists like Jones rarely conduct real research or protect heritage sites. Instead, their expeditions are funded by mysterious donors or museums, turning archaeology into a business transaction rather than a scholarly pursuit.

Hollywood’s archaeologists rarely teach or publish; they fight villains, dodge traps, and uncover mystical relics.

Their work resembles private investigation or treasure hunting more than academic study, reinforcing public misconceptions about how archaeologists earn their living and what they actually do.

Cinematic archaeologists are often cast as protectors of ancient treasures, defending artifacts from greedy collectors or corrupt rivals. The hero’s morality lies in wanting to share discoveries with the world—usually through museums—while villains, like Belloq in Raiders of the Lost Ark, seek personal profit.

This trope has shaped how audiences view the discipline: archaeologists as guardians of humanity’s heritage. Yet it also distorts reality. In film, sites are destroyed without regret once the artifact is secured, while in real life, preserving context is crucial to understanding the past.

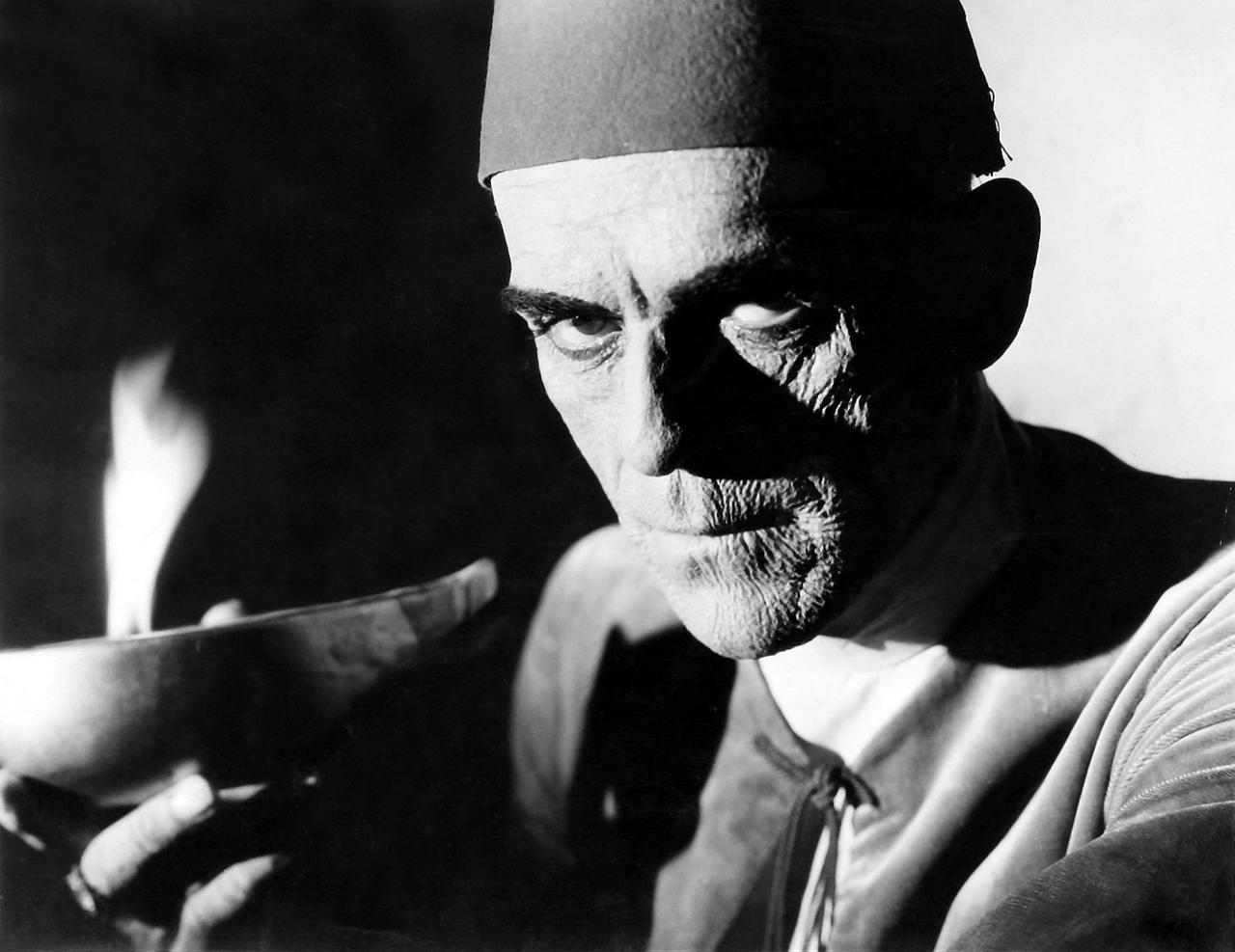

Since the 1930s, mummy films have tied Near Eastern archaeology to horror. From Boris Karloff’s "The Mummy" (1932) to "The Mummy Returns" (2001), the message has remained the same—disturbing the past brings consequences. In these stories, ancient curses and forgotten technologies return to punish modern intruders.

Whether the danger comes from resurrected priests or hidden weapons, cinema warns that “some things are best left buried.”

Film has also shaped perceptions of gender in archaeology. Male archaeologists are often depicted as either intellectual British scholars or rugged American adventurers. Female archaeologists, by contrast, tend to fall into two categories: glamorous adventurers like Lara Croft or bookish scholars who transform into heroines once they remove their glasses, as in "The Mummy" (1999). Both archetypes reflect long-standing stereotypes—women are either empowered fantasies or damsels in distress.

Even within these roles, sexual morality determines heroism. A woman who uses her sexuality, like Elsa Schneider in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, is portrayed as untrustworthy, while the chaste yet strong Lara Croft becomes an acceptable model of independence.

Hollywood’s obsession with the Near East has also perpetuated “Orientalist” views. Films set in deserts—from "The Mummy" to "Stargate"—portray the Middle East as mysterious, dangerous, and filled with secret societies guarding ancient wisdom.

In most archaeological films, local scholars appear only as silent assistants or noble guardians protecting ancient secrets. Rarely are they shown as intellectual equals to Western protagonists. This hierarchy—rooted in colonial-era adventure narratives—portrays knowledge as something owned and interpreted solely by Western heroes, while Middle Eastern or non-Western characters remain on the periphery of discovery and decision-making. The majority of local participants are further relegated to labor roles, depicted primarily as excavation workers or guides rather than as researchers or thinkers contributing to the interpretation of the past.

Despite these distortions, archaeology’s cinematic image continues to shape public perception. Movies may misrepresent the science, but they also keep interest in the past alive. As McGeough notes, understanding how audiences interpret these heroic and mystical portrayals can help archaeologists communicate more effectively about their real work—work that relies not on whips and revolvers, but on patience, context, and care.