Recent diplomatic contacts between Israel, Greece, and the Greek Cypriot Administration have pushed historical interpretations of the Ottoman past back into international political discussion.

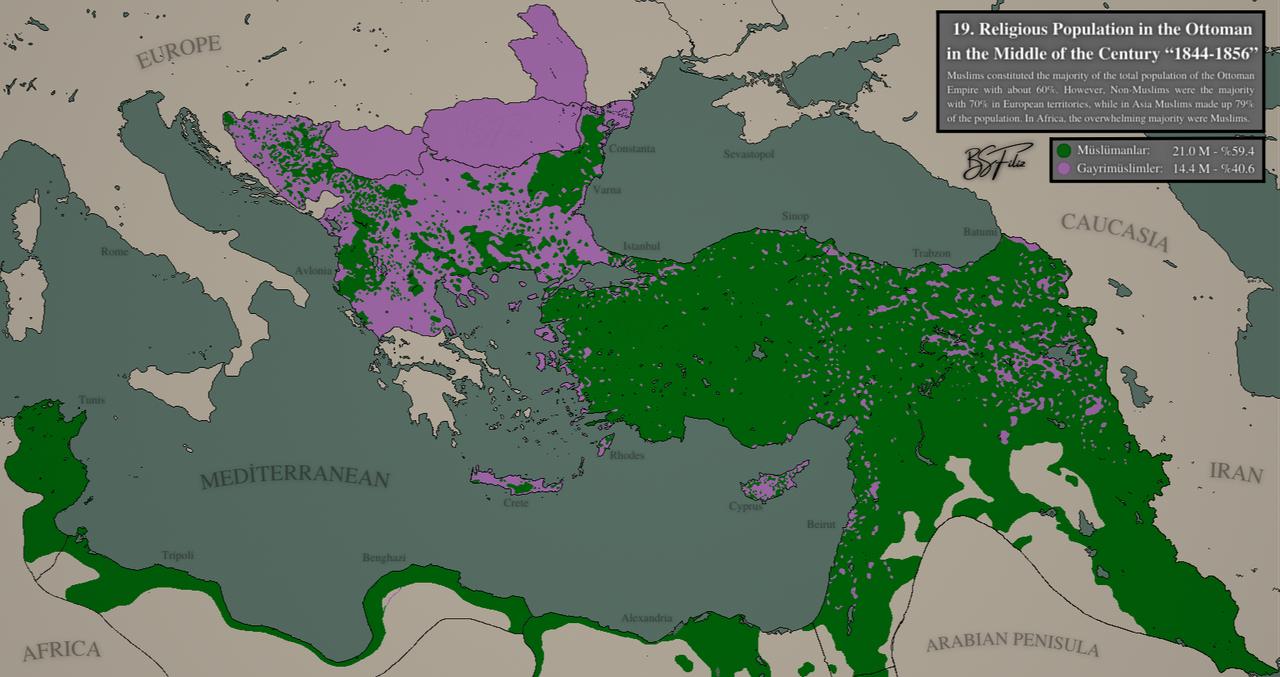

References made during these meetings to alleged grievances tied to former Ottoman territories have, in turn, brought older questions of identity, terminology, and historical continuity in the Eastern Mediterranean back into focus. At the center of this renewed debate stands the Greek Orthodox community, traditionally known as the Rum, whose historical position is often framed in ways that differ sharply from the lived realities of the Ottoman period.

Historical records show that the Rum community in Türkiye cannot be reduced to an extension of modern Greece. The term “Rum,” derived from “Roman,” points to the Eastern Roman or Byzantine heritage rather than to the Greek nation-state that emerged much later.

For centuries, this identity took shape within Anatolia, where indigenous populations gradually adopted the Greek language and culture while remaining embedded in the region’s social fabric.

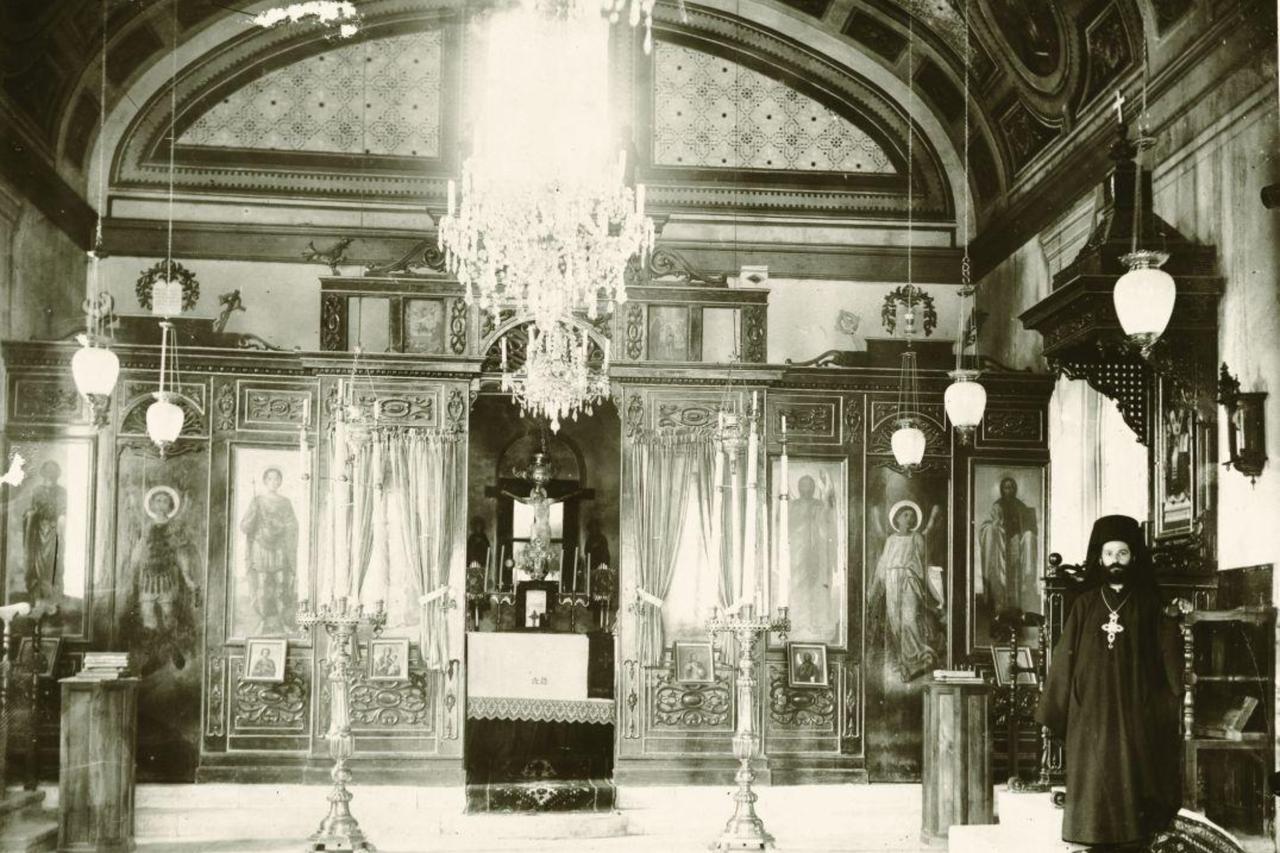

Within the Ottoman administrative order, the Rum were one of several long-established communities, living alongside Muslim populations and other non-Muslim groups such as Jews. This coexistence was not shaped primarily by confrontation, but by a legal and social framework that allowed different groups to carry on with their own traditions while remaining tied to the imperial center.

For nearly a millennium, “Rum” has been the standard term in Turkish for Greek Orthodox populations living in lands once governed by the Eastern Roman Empire. Historically, the word “Greek” referred more narrowly to areas such as the Peloponnese and parts of northern Greece. The Rum identity, by contrast, reflected a broader and more layered background rooted in Anatolia and the Byzantine legacy.

In recent years, a growing use of phrases such as “the Rums” in English and French publications has drawn attention. Critics argue that these expressions sometimes replace established descriptions like “Greeks of Türkiye” or “Istanbul Greeks,” which may better convey both geography and citizenship.

Members of the community themselves often switch terms depending on language, using “Rum” in Turkish, “Romioi” or “Ellines” in Greek, and “Greek” in other foreign languages, without altering the core sense of belonging tied to Anatolia.

According to experts, this is precisely why today’s Greek Cypriot community is also known in Greek as Ellines. In historical and cultural terms, however, the area commonly referred to as the “Greek part of Cyprus” is not simply Greek in a modern national sense, but rather the region inhabited by Cypriot Rum, whose identity is rooted in the Eastern Roman and Anatolian tradition rather than the contemporary Greek nation-state.

The broader Ottoman approach to religious diversity also shaped the experience of the Rum community. Long before the modern era, the empire acted as a refuge for groups facing persecution elsewhere in Europe. Jewish communities, in particular, began arriving in Ottoman lands as early as the late 14th century, fleeing expulsions from regions such as Hungary, France, and parts of Italy.

The most well-known migration followed the 1492 expulsion of Jews from Spain, when Sultan Bayezid II opened the empire’s gates to those displaced by the Alhambra Decree. Similar protection was extended to Jews expelled from Portugal in 1497. These communities were able to keep up their religious life and communal structures, while also contributing economically and socially to Ottoman cities.

The mechanism that held this diversity together was the Millet system, a legal arrangement that recognized non-Muslim communities as semi-autonomous bodies. A “millet” was a religious community officially acknowledged by the state and allowed to run its own internal affairs. This included family law, education and religious institutions, all overseen by community leaders.

For the Rum and Jewish populations, this meant formal recognition rather than simple tolerance. Although they were classified as “zimmi,” or protected subjects, they enjoyed administrative freedoms that were rare in contemporary European states. The central government largely stayed out of private and cultural life, which helped different communities live side by side over long periods.

Coexistence did not rule out tension, and the Ottoman state sometimes stepped in to prevent conflicts between minority groups. One recurring issue involved false “blood libel” accusations against Jews, made by some Christian communities, including elements among the Rum and Armenians.

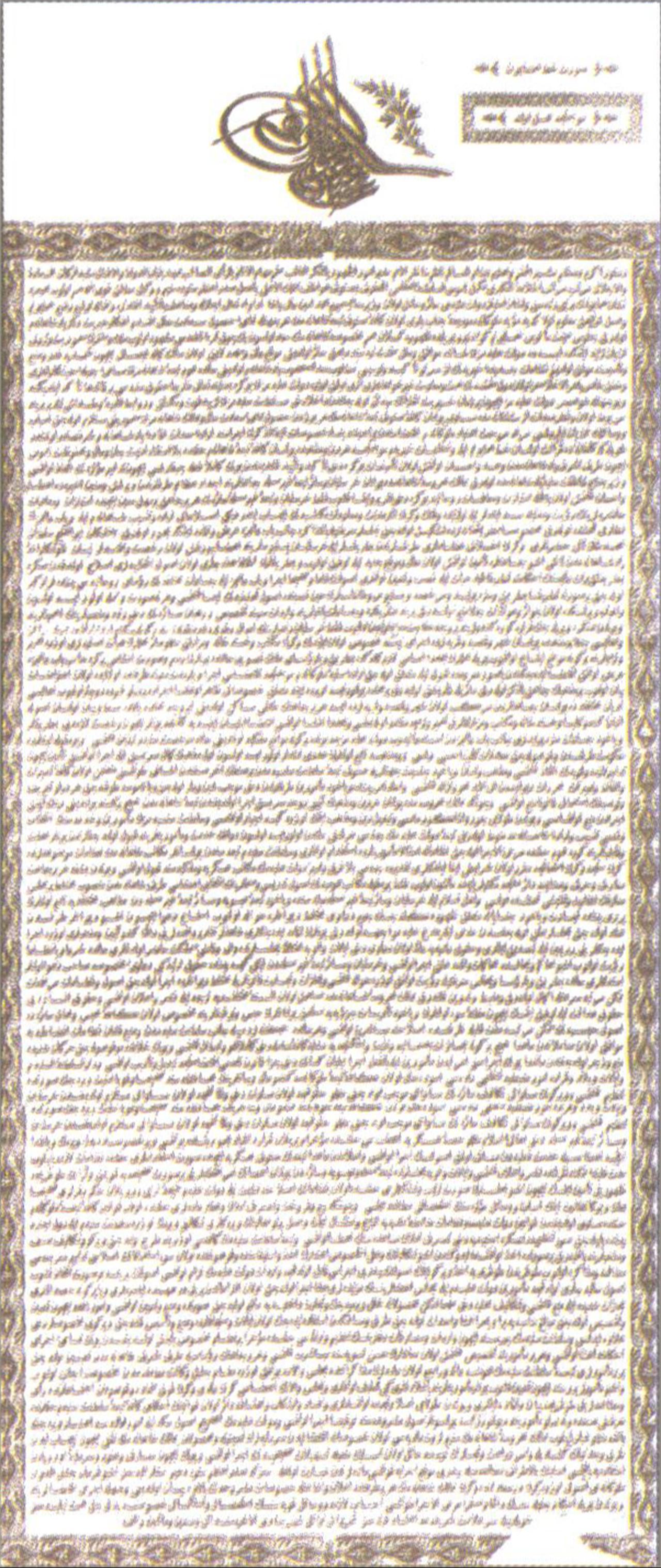

In 1840, Sultan Abdulmecid issued an imperial decree stating that such accusations were unfounded and contrary to both Islamic principles and state law.

The decree underlined that the Jewish community was under direct imperial protection and that harassment would not be accepted. This episode illustrates how the Ottoman ruler positioned himself as a guarantor of order among different religious groups.

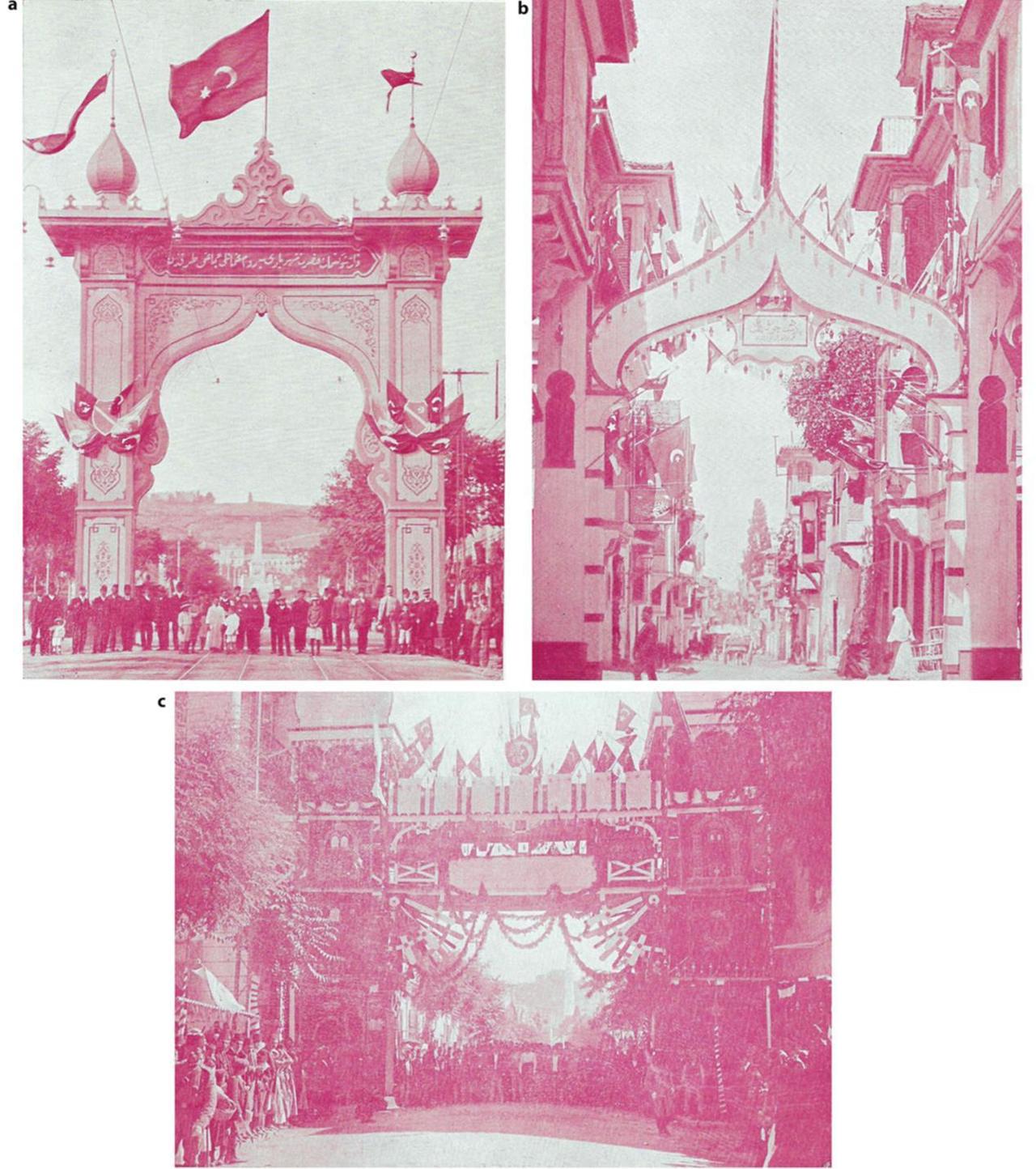

By the 19th century, the Ottoman state began to shift its legal structure through the Tanzimat reforms.

The 1839 Edict of Gulhane and the 1856 Reform Edict aimed to redefine all inhabitants as equal Ottoman citizens, regardless of religion. These measures allowed non-Muslims to serve in the military and hold senior state positions, while still keeping up the religious autonomy of the millets.

This transition marked a move away from purely communal identities toward a shared civic framework. For the Rum, Armenian and Jewish communities, it meant being increasingly recognized not only as protected groups, but as integral participants in a modernizing state.