The Sept. 12, 1980 coup left a profound mark not only on Türkiye’s political order but also on its cultural and intellectual fabric. The coup cannot be understood merely as a military operation; it became a rupture etched into the collective memory, inaugurating a new era in which everyday life and cultural production were reshaped. The process of silencing spread from streets to university cafeterias, from village squares to urban cultural centers, redefining the freedom of the pen, the stage, and the melody. In Türkiye, literature cannot be separated from politics; politics fed the language of literature, while literature recorded the spirit of the political climate.

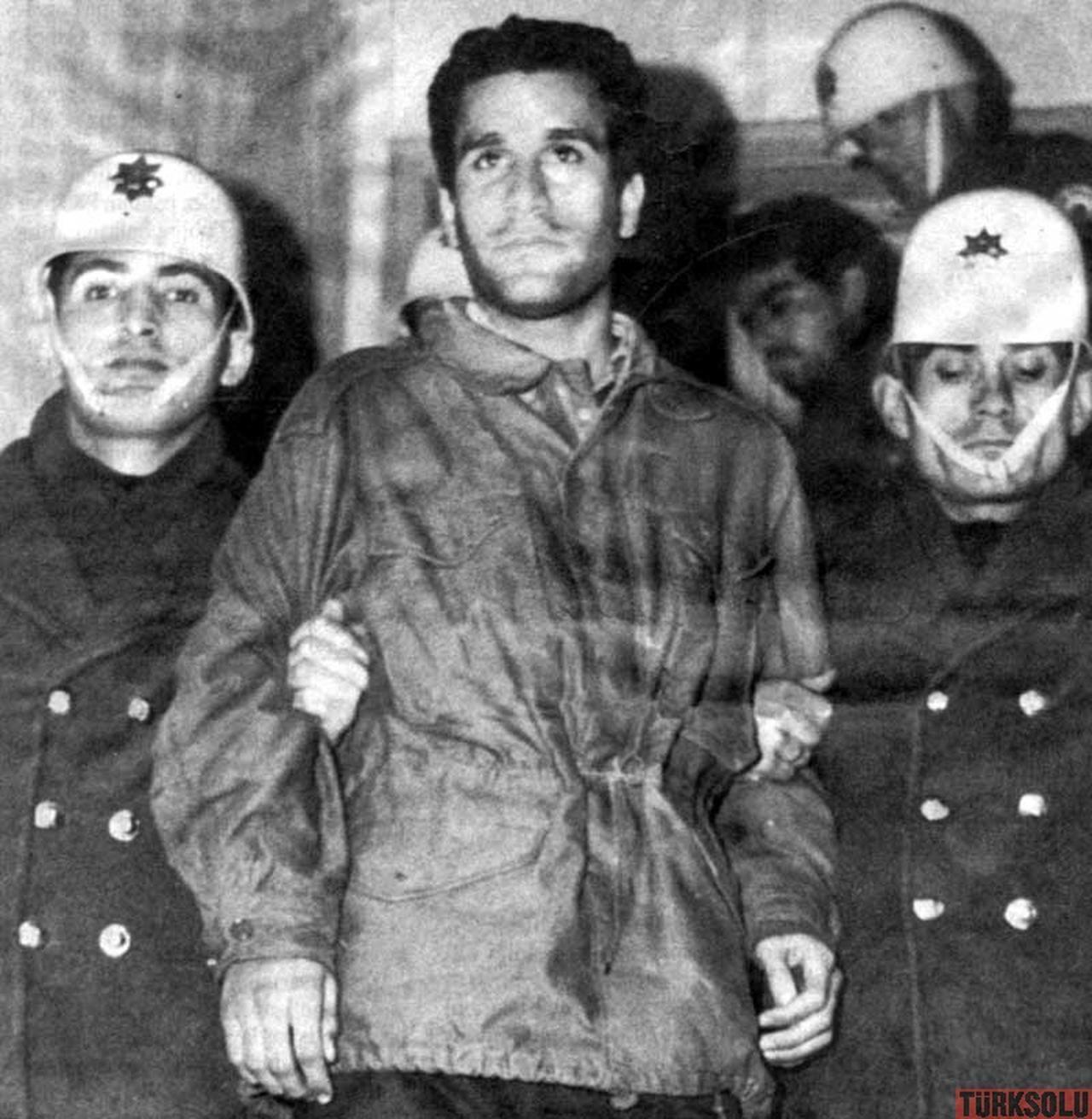

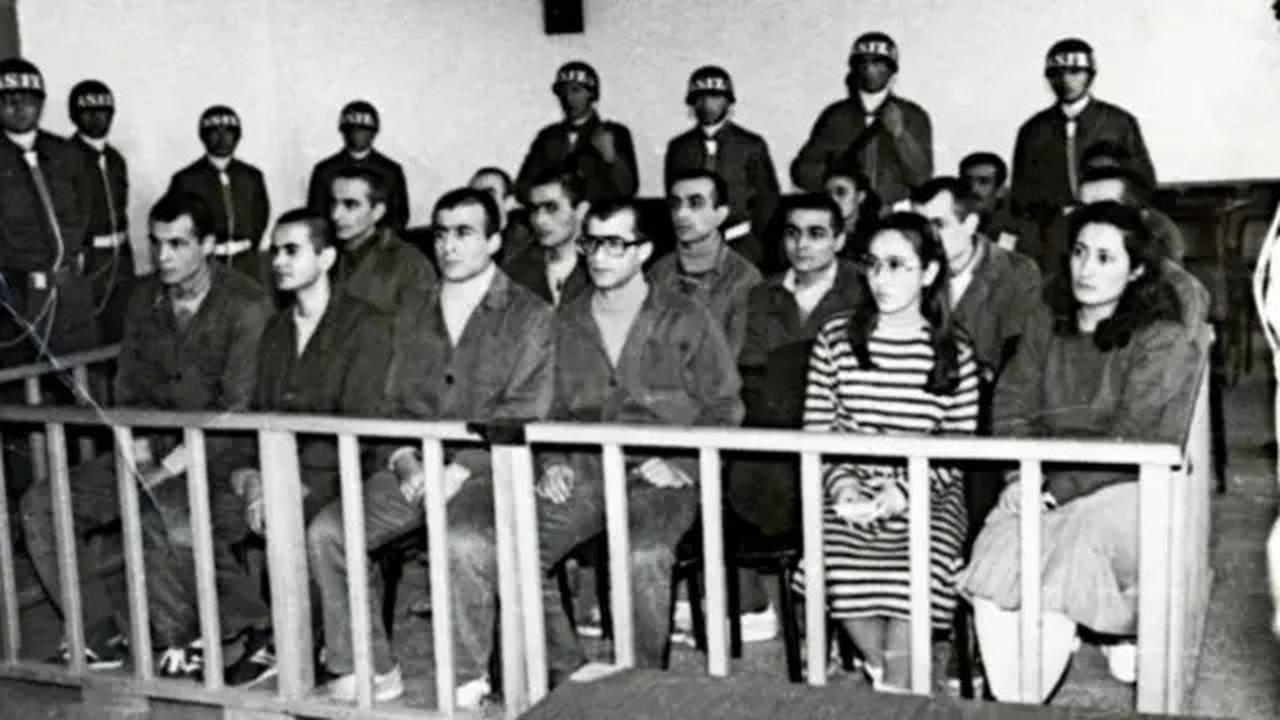

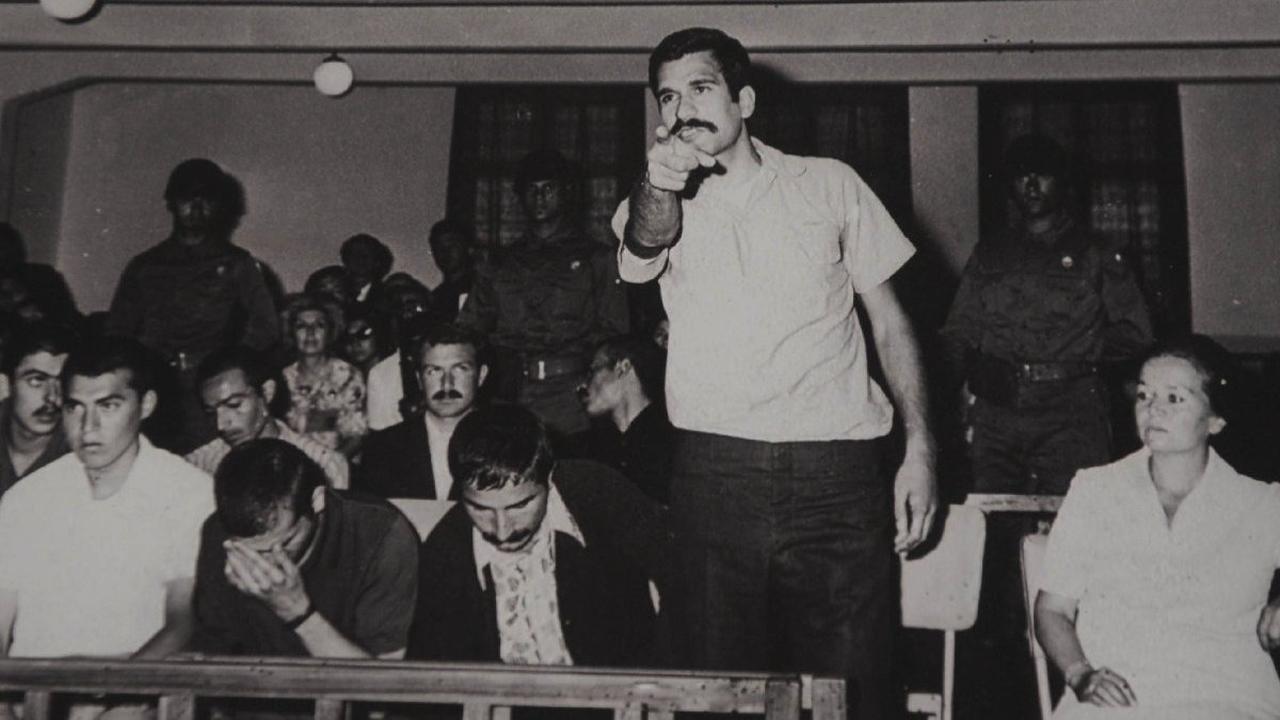

By the late 1970s, Türkiye was engulfed in an ideological struggle between right and left that permeated every facet of daily life. Coffeehouses, lecture halls, union meetings, factories … everywhere, ideological divisions dictated life. Young people fell in street clashes, and newspapers daily reported new murders, showing that violence had become normalized. The army intervened under the pretext of “restoring order.” This pursuit of order disciplined politics, thought, speech, and cultural life.

To understand the coup’s effects, two literary currents stand out: the left’s focus on social struggle, and the right’s emphasis on traditional-national values. In leftist works, social inequality, the struggles of workers and peasants, and political resistance were central themes.

Yasar Kemal’s "Ince Memed" series portrayed the resistance of villagers against landlords and injustice. Memed’s line, "The landlord does not look, Memed does; Memed will one day return to the face of the country," combined individual courage with a quest for social justice.

Fakir Baykurt’s "Yilanlarin Ocu" narrates villagers’ confrontations with landlords and the state within a framework of class struggle: "The villagers were silent, but the anger in their eyes shone like stars in the sky."

In "Tirpan," Baykurt explored the resilience of village women, offering a different perspective on social inequality. Haldun Taner’s "Kesnali Ali Destani" depicted Ali’s conflicts with society and authority, using humor to highlight the contradictions of the era.

The rightist literary stream revolved around tradition, religion, and national values. Necip Fazil Kisakurek’s poem "Sakarya Turkusu" expressed individual and societal reckoning: "Equal to the pangs of conscience, the Sakarya roars," while Sezai Karakoc’s thought of "Dirilis" turned literature into a call for ideological awakening.

These works resonated with the post-coup state’s emphasis on national culture and were widely embraced.

Understanding this period requires more than looking at banned books; one must examine life itself. Here, Rifat Bali is instructive. In "Tarz-i Hayattan Life Style’a," Bali vividly depicts the socio-cultural atmosphere of post-coup Türkiye that also shaped literature.

By the 1980s, Türkiye had stepped into a consumer society. Political repression and censorship mattered, but so did cultural engineering. Bali emphasizes that one’s identity and social standing were determined by where they lived, which cafe they frequented, what brand of cigarette they smoked, and which foreign words they sprinkled into conversation. This reality seeped into literature.

Novels that once revolved around village, land, and class struggle were replaced by stories of urban dwellers’ anxieties, love lives, loneliness, and consumption habits. Since 1980, Türkiye’s society has transformed rapidly. With the dominance of the free-market economy, consumption became the defining factor of identity. Every day life took on color and an Americanized flavor. Businessmen, who once sought invisibility, began to appear daily in newspapers, seeking “intellectual” recognition. Journalism itself evolved; a new type of reporter emerged, closely tied to political power.

Lifestyle columns and projects celebrating a Europeanized yet nationalist “New Turkish Citizen” turned columnists into new aristocrats. Young, urban, well-educated, high-income Turks moved away from the “dark masses” into gated communities. Fine dining, cigars, and wine became status symbols. Nostalgia for Pera is intertwined with interest in non-Muslim communities. Politicians increasingly competed for attention through their image.

Bali’s book strikingly illustrates the changes during Ozal’s era and afterward. Although Türkiye’s first attempts at a market economy began with the Democrat Party, they were interrupted by the 1960 coup. The post-1980 period created an entirely different Türkiye. With the Jan. 24 decisions institutionalizing the market economy, imported goods entered Türkiye, glamor and luxury were promoted, and capital became visible—brands like Boyner and Sabanci rose to prominence. With globalization, Türkiye came to be called “Little America.” From cuisine to entertainment, from fashion to artistic taste, everything was shaped by Western models.

Book debates were centered in Istanbul, highlighting tensions between old Istanbul capitalists and new wealth, and the complaints of provincial migrants to the city. Okan Bayulgen famously expressed one such sentiment, wishing everyone would return to where they came from. The broader lesson: the post-1980 era sought to create a consumer society, imposing elite status through food, drink, festivals, and music without regard for traditional social values. These debates mark the starting point of the evolution of today’s conservative society’s consumption habits.

Latife Tekin’s "Sevgili Arsiz Olum" (1983) tells of a family migrating from village to city and their alienation in Istanbul. Tekin describes a character: "The whole city was a stranger, every street waiting to crush me." This captures the psychological effects of urbanization and societal disintegration. Adalet Agaoglu’s "Uc Bes Kisi" (1984) portrays middle-class individuals’ apathy toward political trauma, reflecting the passivity of the period. In Bilge Karasu’s "Gece," individuals struggle to survive in their inner worlds under totalitarian pressure: "Those who could hear their own voice in the silence prevailed."

The literary works of the 1980s foregrounded individualization. Ismail Ugur Aksoy described characters as detached from intellectual pursuits, distracted by personal pleasures and daily amusements—concretely illustrating literature’s relation to the political and economic climate.

According to Bali, post-1980 Türkiye saw art galleries and cultural spaces reshape under Western aesthetic influence. Galleries ceased to be mere exhibition sites; they became venues for the new wealthy to socialize and signal status. Art became a visible marker of elite identity and occupied the center of cultural consumption. Istanbul’s Pera district became emblematic of this transformation, with Beyoglu and Pera cafes, galleries, and cultural spaces serving as hubs of a new Western-oriented social and cultural rhythm.

The media also functioned as an ideological representative of this elitism. Columns and lifestyle content shaped not only daily life but the cultural codes of society. Consumption habits became markers of social prestige and belonging. Newspapers, magazines, and television programs made elite tastes visible, normalizing them as a way of life.

Seen in this light, artistic resistance and individual creativity, alongside the rise of elitism, represent two sides of the same era. Post-coup repression forced art to resist, while Western-oriented cultural spaces and lifestyles in urban centers revealed the societal and cultural transformation Türkiye underwent.

Music and theater emerged as new forms of resistance under repression. Concerts by musical groups were canceled, songs banned. Mustafa Unlu recounted the period in a documentary: "Our songs were banned, our concerts canceled. Art became a tool of resistance."

Censored theater texts reached audiences through symbolic gestures. For instance, the play "Ferhunde Hanimlar" used coded scenes to convey critique. Young people singing in the streets under police watch exemplified art’s role as a language of resistance.

The feminist movement influenced art and literature. Adalet Agaoglu explored female characters’ entrapment under state oppression and gender inequality. Nil Yalter’s 1982 "Body Politics" presented the female body not as an aesthetic object but as a symbol of social control: "The female body is not merely an aesthetic object; it is a symbol of societal oppression and control. I had to make this visible." Agaoglu explained, capturing the spirit of the era.

In popular culture, the fusion of music with the vernacular, as in arabesque, effectively conveyed society’s emotions and hardships. Orhan Gencebay wrote in "Dil Yarasi": "My heart burns, consumed by your love," turning individual suffering and social uncertainty into a symbol. Pop culture—through television, music cassettes, and shows—reached mass audiences, channeling youth into apolitical amusements.

Ara Guler’s 1981 photographs of Beyoglu captured children playing under streetlights in shantytown neighborhoods, their faces reflecting both poverty and hope—visual testimony to the coup’s imprint on collective memory.

In the visual arts, repression and censorship were evident. Post-coup exhibitions in Istanbul and Ankara favored state-approved works, forcing independent artists to present privately. Abidin Dino’s early-1980s drawings depicted social isolation and deserted cities, while Erol Akyavas’s abstract works symbolically reflected the era’s anxieties without direct political statements.