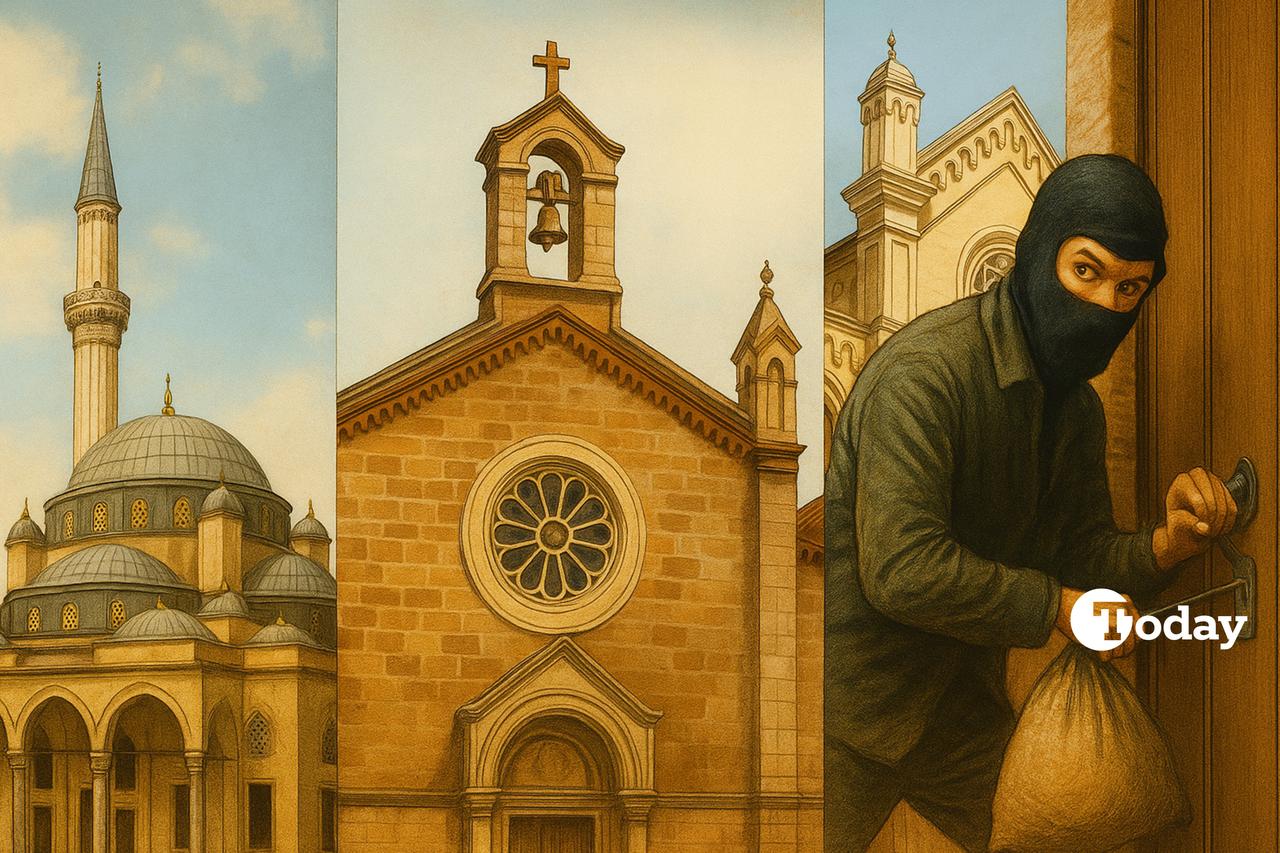

At the turn of the 20th century, the Ottoman Empire witnessed a shocking wave of thefts targeting one of its most revered spaces—mosques, churches, and synagogues.

In the heart of the empire, where religion was deeply entwined with everyday life, robbing places of worship was considered not only a crime but a moral collapse that demanded firm punishment.

While modern crime often focuses on banks or luxury stores, in 19th-century Türkiye, sacred spaces became targets. Items stolen ranged from candlesticks and Qurans to donation boxes and even architectural elements like door knockers and marble slabs. These were not merely material losses but attacks on the sacred trust of a community.

According to Ottoman records, theft in ibadethane (places of worship) surged in the late 1800s and early 1900s, prompting swift legal and administrative responses. The thieves were not just driven by poverty—some were opportunists, repeat offenders, or individuals exploiting legal loopholes.

The Ottoman Empire maintained a dual legal system of Sharia (Islamic law) and customary law (urf). Theft in places of worship was treated with exceptional severity. Ottoman penal codes considered such crimes under the category of "public morality offenses," which could lead to harsh sentences such as forced labor, exile, or long-term imprisonment.

Courts often interpreted theft from mosques as an assault on communal dignity. Judgments reveal that courts aimed not only to punish but to deter by making examples of convicted offenders.

For instance, one thief caught stealing mosque candlesticks in Istanbul’s Eyup district was sentenced to seven years of forced labor in the docks—an unusually heavy punishment for what might be considered petty theft today.

Court records from the era paint a diverse picture of the culprits. They included janitors, errand boys, traveling merchants, and even religious caretakers. Some were caught red-handed, while others were traced through black market sales of stolen religious artifacts.

In some cases, confessions under interrogation hinted at criminal networks operating with surprising organization.

Thieves sometimes visited the same mosque repeatedly or spread their thefts across different districts to avoid detection.

The Ottoman public, particularly local mosque communities, played a vital role in both crime prevention and judicial proceedings. Mosque wardens, known as "bekci," collaborated closely with the police and were often the first to report suspicions. Neighbors also testified in court, frequently identifying suspects or detailing unusual behavior.

This communal vigilance turned sacred theft into a matter of public scandal, widely discussed in local newspapers of the era. Some articles decried not just the crime but the broader erosion of societal values.

As thefts increased, the state responded with stricter controls. Surveillance around religious buildings intensified, with regular inspections and better documentation of sacred objects.

Donations were carefully recorded, and new safekeeping protocols were introduced, including locked containers and nighttime security shifts.

These reforms reflect how the Ottoman state modernized its crime response, balancing religious respect with bureaucratic efficiency. They also illustrate the early forms of crime prevention policies that would later influence the Republic of Türkiye.

While the number of cases appears high in legal archives, historians caution against reading this solely as a surge in crime. Some argue that the increased documentation reflects a changing Ottoman legal system — one more attuned to transparency, record-keeping, and citizen protection.

Others interpret the rise in sacred theft as evidence of social anxiety and economic distress during the empire’s last years.