The bronze statue of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, which had been kept in the Cleveland Museum of Art for decades, has finally returned to Türkiye after a prolonged legal and diplomatic process.

Before its repatriation, U.S. museum officials requested three months to keep the statue for a final public display. Türkiye accepted this request under the condition that the late Professor Jale Inan, who was instrumental in identifying the statue’s origins, would be commemorated during the display. As a result, the museum hosted an exhibit featuring photographs and information about Inan, regarded as a pioneering figure in Turkish archaeology.

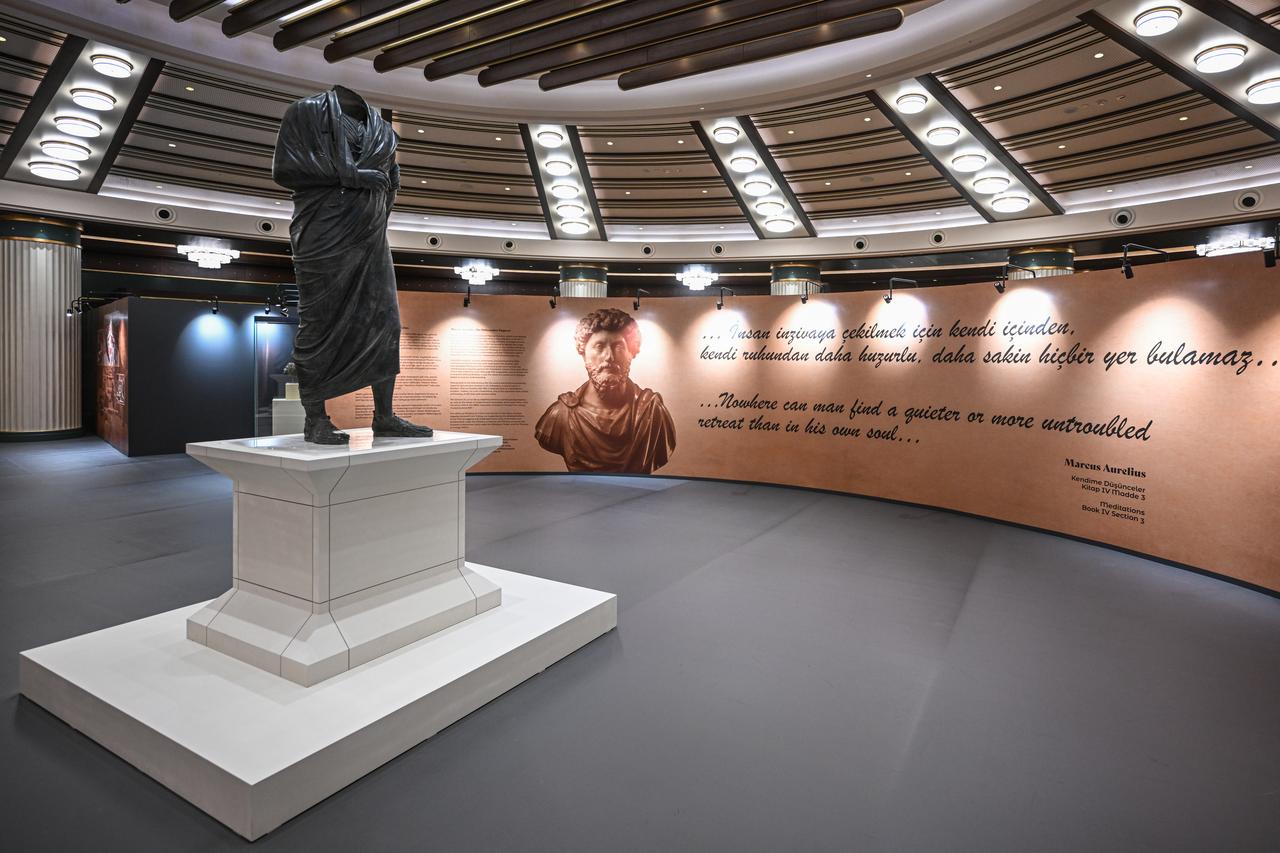

The statue was unveiled in Türkiye during the launch of the “Golden Age of Archaeology” exhibition at the Presidential Library in Ankara, with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan attending the opening. This marks the first time that the Turkish public can view the statue, which was looted from the ancient city of Boubon in southwestern Türkiye and trafficked abroad during the 1960s. The exhibition features 570 artifacts, including 485 items on display for the first time, brought together from 90 excavation sites across the country.

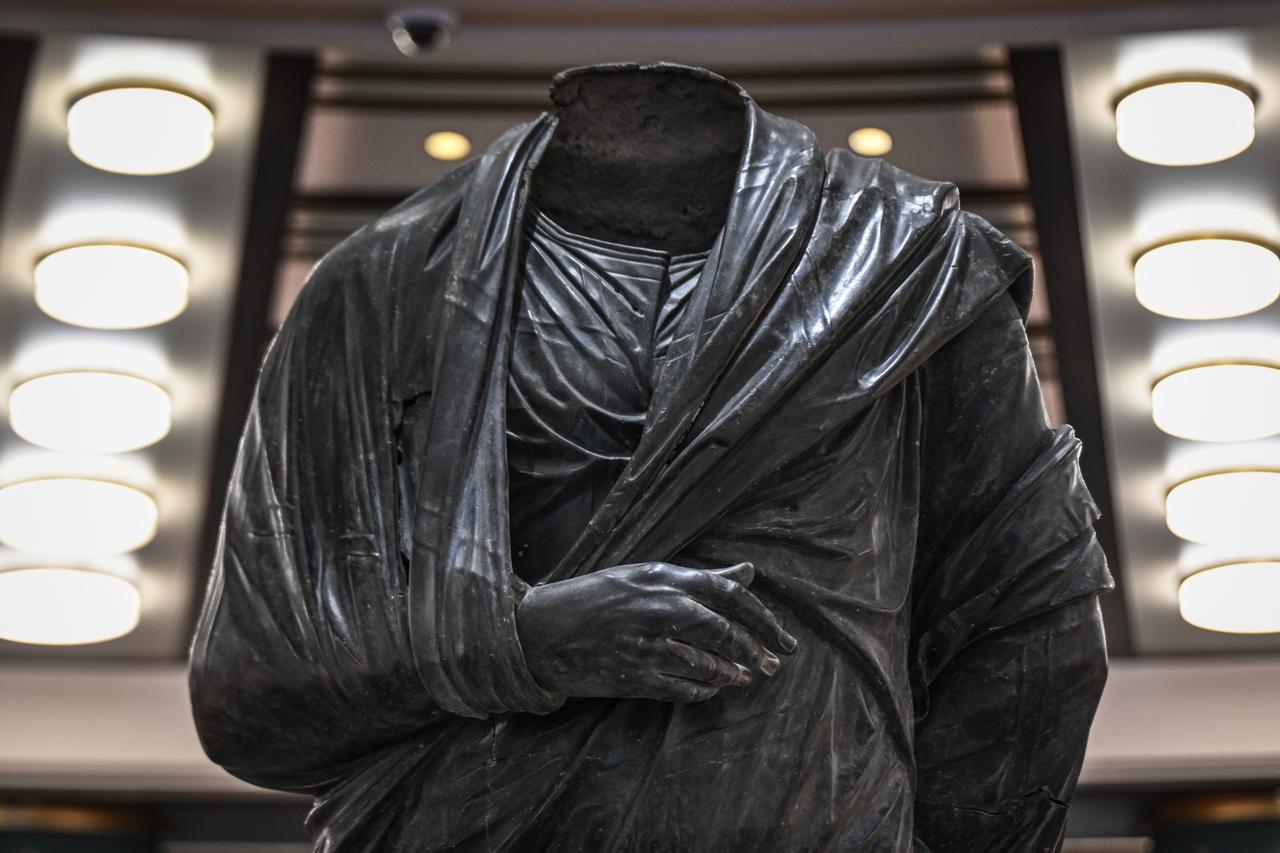

Zeynep Boz, head of the Department for Combating Illicit Trafficking at the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, emphasized the significance of the statue’s return. She underlined that Emperor Marcus Aurelius, known for his philosophical writings and leadership during turbulent times in the Roman Empire, was also a leading figure in Stoic philosophy. The bronze statue, she noted, is a rare survivor, as bronze sculptures were often melted down throughout history to mint coins, produce weapons, or make household items.

Boz explained that the statue’s return was the outcome of years of work. The process began in the 1970s, when Professor Inan first identified the statue as originating from Boubon after seeing it in the United States. Legal efforts intensified in 2021, when Turkish authorities reopened the Boubon investigation, ultimately proving the statue’s origin by matching the base of the sculpture to the void left in a plinth found at the original site.

According to Boz, the Cleveland Museum’s request to hold on to the statue for three more months was accepted only after Türkiye stipulated that Professor Inan be commemorated on site.

“We thought, just as we had formed a connection to the statue, Americans who had seen it for many years might feel the same,” said Boz. The museum agreed, and during this period, it exhibited photos and details from Inan’s life alongside the statue.

Boz pointed out that the statue arrived without its head, and its whereabouts remain unknown. “We don’t know where it is or even if it still exists,” she said, adding that it may have been lost or destroyed during historical invasions or religious upheavals. She described the missing head as a powerful symbol of the destruction caused by cultural vandalism.

Deputy Director General of Cultural Assets and Museums, Bulent Gonultas, stated that the exhibition also includes significant finds from the Tas Tepeler Project, a major archaeological initiative in southeastern Türkiye. Among the most compelling artifacts are life-sized human sculptures and animal figures carved into stone blocks from the Karahantepe site, offering valuable insight into prehistoric social and ritual life.

Gonultas added that Tas Tepeler’s recognition at last year’s Shanghai Forum as one of the world’s leading archaeological projects reflects Türkiye’s growing prominence in the field. He emphasized that the “Golden Age of Archaeology” exhibition represents the strength of Turkish archaeological research, rooted in 180 years of continuous exploration.