A new study revealed how prehistoric hunter–gatherers in north-eastern Europe extracted animal teeth to produce personal ornaments, uncovering a link between everyday cooking practices and symbolic craftwork.

Drawing from experimental archaeology, researchers have for the first time demonstrated how ancient communities used specific heating methods to remove teeth without damaging them.

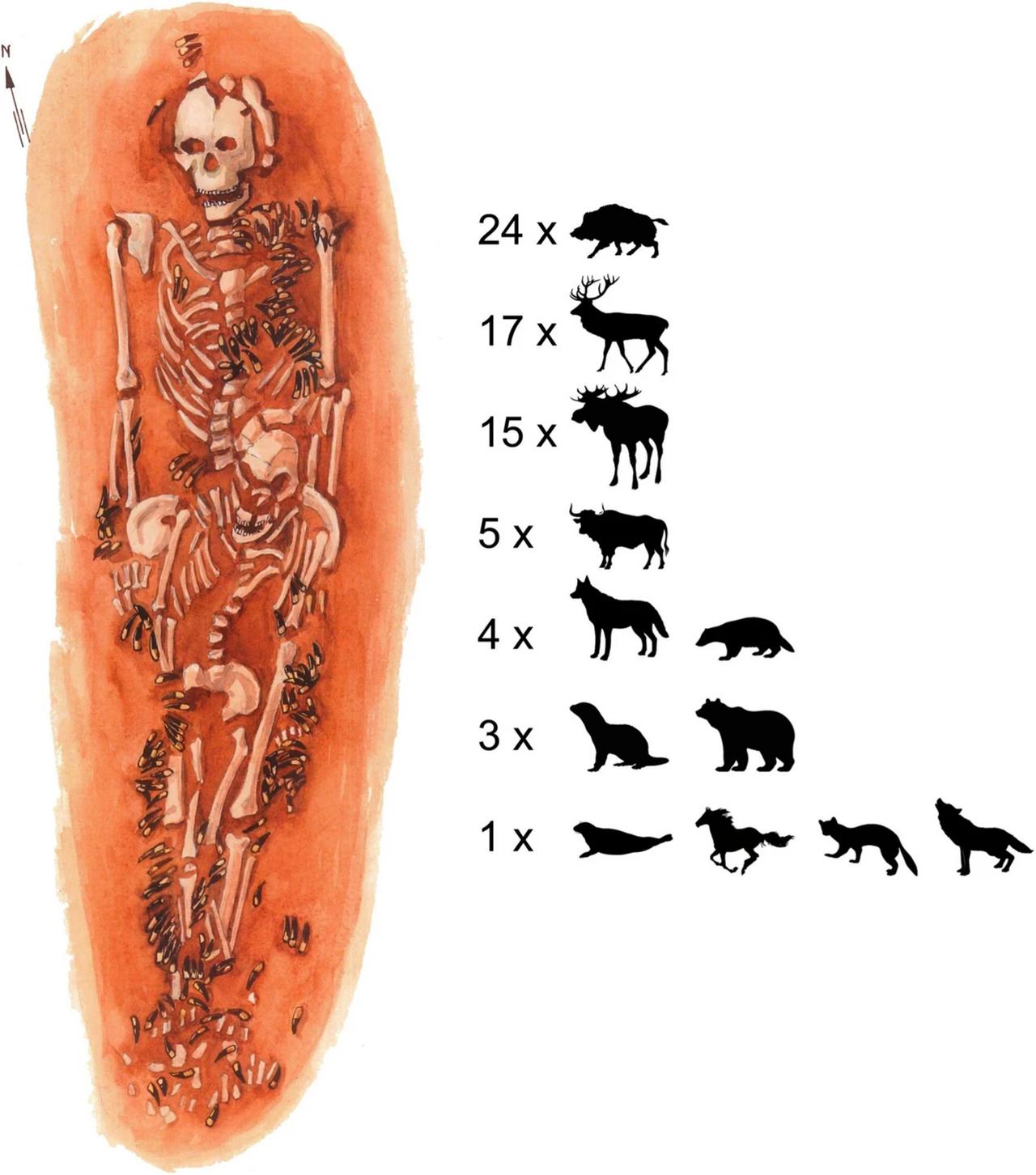

The investigation centers on the Zvejnieki cemetery site in present-day Latvia, where more than 2,000 animal teeth—mostly from deer and other local fauna—have been unearthed from graves dating between 7,500 and 2,500 B.C. While these artifacts have long been interpreted as decorative or symbolic items, the newly published research highlights the practical and often overlooked process of tooth extraction as a distinct stage in prehistoric material production.

To uncover how these teeth were removed from skulls, the researchers experimented with seven different methods. These included direct cutting, percussion (striking), air drying, soaking, heating over fire, wet cooking, and pit steaming. Wet cooking and steaming—methods involving boiling or heating animal heads in pits—proved to be the most successful.

These techniques allowed the teeth to be removed cleanly, without cracking or splitting, which is essential for crafting durable pendants. The process also had added benefits: it softened the meat, making it edible, and left bones intact for potential use as tools.

The study, published in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, marks the first time that experimental archaeology has been applied to the initial stage of tooth pendant production at Zvejnieki.

The findings suggest that tooth extraction was not a secondary activity or opportunistic by-product of butchery, as previously assumed. Instead, it was a deliberate and time-sensitive task embedded in daily routines—especially those related to food preparation.

Lead researcher Aija Macane explained that “our experiments show that tooth extraction was a deliberate, time-sensitive process embedded in daily life, especially cooking practices.” This shifts previous understandings, which assumed that teeth were either scavenged or widely available with little effort.

By situating tooth extraction within food preparation and domestic work, the study broadens the picture of prehistoric life. These teeth—later shaped into pendants—did not simply appear as finished objects in burials. They were created through a complex series of interactions with animals and environments, involving hunting, cooking, crafting, and ritual deposition.

The research calls for a closer examination of the chaine operatoire, or sequence of actions in artifact production. This approach helps archaeologists better understand how everyday activities contributed to personal adornment and cultural identity.

Researchers hope that future work will explore how these practices compare to those involved in butchery or the extraction of human or carnivore teeth, which also appear in archaeological contexts. The goal is to map out the full "life history" of each ornament—from the capture and processing of the animal, to the crafting and eventual burial of the pendant.

As Macane put it, “by better understanding the extraction process, we gain deeper insight into the life histories of tooth pendants—from animal capture and processing, to ornament crafting, use, and final deposition.”

The study provides a richer understanding of the technological and cultural practices of prehistoric communities and highlights how ordinary tasks such as cooking played a crucial role in shaping symbolic and personal objects that endured long after the people who made them.