Archaeologists working in central Tunisia have uncovered what they describe as the second-largest industrial olive oil production complex known from the entire Roman Empire, shedding light on how a frontier estate operated within the oil supply system that served the city of Rome.

The excavation, led by Ca’ Foscari University of Venice in cooperation with Tunisian and Spanish institutions, is taking place in ancient Cillium, a border area near today’s frontier with Algeria, in the heart of the Jebel Semmama massif. In this high-steppe landscape, marked by a continental climate with sharp temperature swings and modest rainfall stored in wells, two ancient olive-growing farms have come to light.

At the core of these farms stands a colossal frantoio, or Roman industrial-scale presshouse, equipped with torcularia – large beam presses dedicated to producing olive oil on a commercial scale. The main press building, or torcularium (a monumental press room within the presshouse), has been identified as the largest frantoio discovered so far in Tunisia and the second-largest known in the Roman world.

The region formed part of Africa Proconsularis and was once inhabited by the musulamii, communities of Numidian origin. It became a complex meeting point between Roman imperial authority, veteran colonists and local Indigenous populations, whose socioeconomic dynamics are only now beginning to be unraveled.

Within this landscape, the site of Henchir el Begar has emerged as a focal point. Researchers identify it with ancient Saltus Beguensis, the center of a vast rural estate in the Begua district that in the second century CE belonged to Lucillius Africanus, described in sources as vir clarissimus. A famous Latin inscription, recorded as CIL VIII 1193 and 2358, preserves a senatus consultum issued in 138 A.D., which authorized a bimonthly market, an event of deep significance in the social, political and religious life of the time.

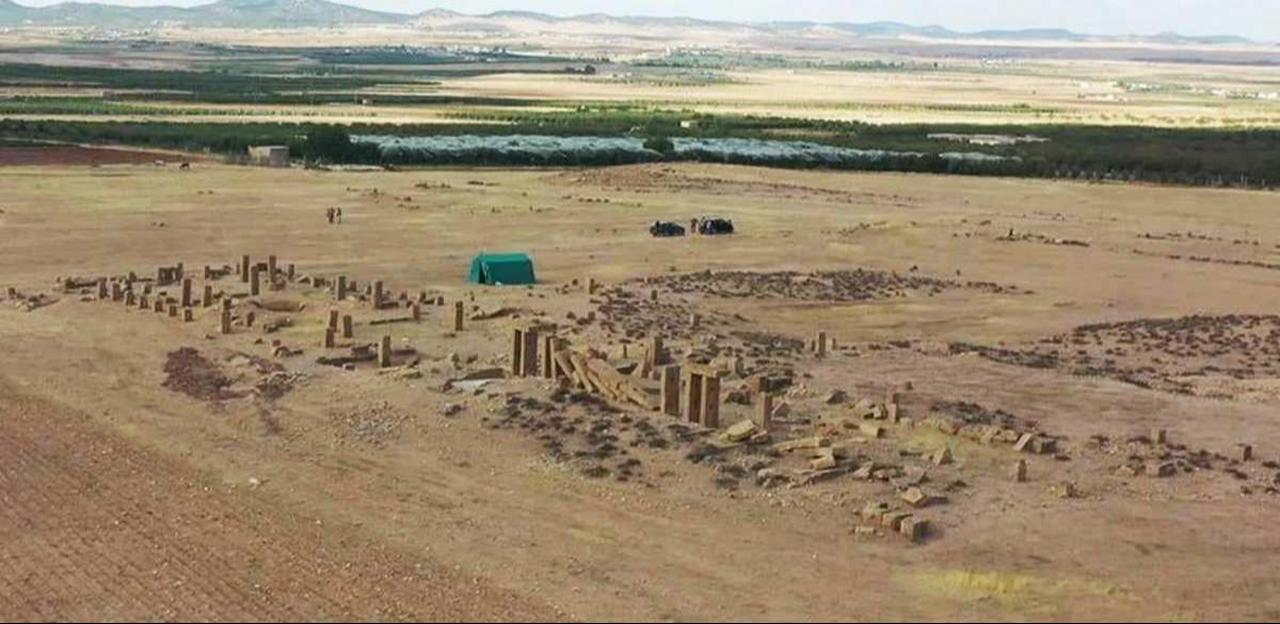

The settlement at Henchir el Begar extends across about 33 hectares and is organized in two main sectors known as Hr Begar 1 and Hr Begar 2. Both sectors contain olive oil production facilities, a water-collection basin and a diversified system of cisterns.

Hr Begar 1 contains the largest known Roman frantoio in Tunisia, dominated by a monumental torcularium fitted with twelve beam presses. A short distance away, Hr Begar 2 preserves the remains of a second installation which is somewhat smaller but still formidable, with eight presses of the same type. Stratigraphic analysis and associated finds suggest that these large-scale structures remained in use from the third to the sixth century A.D., spanning several centuries of political and economic change.

Around the production buildings, archaeologists have identified a rural vicus, a residential area where colonists and possibly segments of the local population lived in close proximity to the presses. On the surface, numerous millstones and stone grinders have been recorded, indicating that grain processing took place alongside oil production and thus highlighting the dual agrarian vocation of the enclave.

Recent geophysical surveys using ground-penetrating radar have mapped out a dense pattern of residential structures and road traces that had not been detected before. The results point to a rural space whose layout and internal organization are far more complex and articulated than previously assumed for this kind of frontier settlement.

The mission is the outcome of an international scientific partnership that was formalized in 2023 at the initiative of Professor Samira Sehili of Universite La Manouba in Tunisia and Professor Fabiola Salcedo Garces of Complutense University of Madrid. The latest campaign also counts on the active participation of Professor Luigi Sperti, Deputy Director of the Department of Humanities and Director of CESAV at Ca’ Foscari, whose role as co-director is backed by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation.

This institutional framework, which links universities in three nations, is opening up new opportunities for joint research into the archaeology of production and, in particular, into olive oil – a defining element of Mediterranean civilizations whose imprint endures to this day.

Excavations in layers dating from the Byzantine period to the modern age have brought to light a series of movable finds. Among the most notable are a bracelet decorated with copper and brass, a projectile made of white limestone and several pieces of architectural sculpture. One striking example is a fragment of a Roman press that had been reused in a Byzantine-era structure, an eloquent sign of the long lifespan and continuous reuse of building materials at the site.

For Professor Sperti, the mission offers an unprecedented window into how frontier regions of Roman Africa were organized in agrarian and socioeconomic terms. As he notes, “Olive oil was a product of paramount importance in the daily life of the ancient Romans, who used it as an essential condiment in cooking, as a body-care product in both athletic and medical contexts, and even—as in the case of lower-quality varieties—as fuel for lighting systems.” Shedding light on the ways this product was produced, marketed and transported on such a vast scale, he adds, creates an exceptional opportunity to bring research, heritage enhancement and economic development together, confirming the relevance of archaeology as a hallmark of excellence for his university.