In the 19th century, as European empires scrambled for dominance across continents, another more subtle battlefield emerged—archaeology. Türkiye’s vast ancient heritage, from the ruins of Troy to the temples of Lycia, became a focal point of what scholars now call archaeo-diplomacy. This practice—blending archaeological exploration with political strategy—offered the Ottoman Empire a unique form of soft power in an age of shifting alliances, colonial aspirations, and cultural rivalry.

As Renaissance humanism evolved into Enlightenment curiosity, European powers increasingly sought to lay claim—intellectually and physically—to ancient civilizations. With the rise of modern archaeology, ancient Greek and Roman artefacts became coveted cultural trophies. But many of those artefacts lay within the borders of Ottoman-controlled Anatolia and the Balkans.

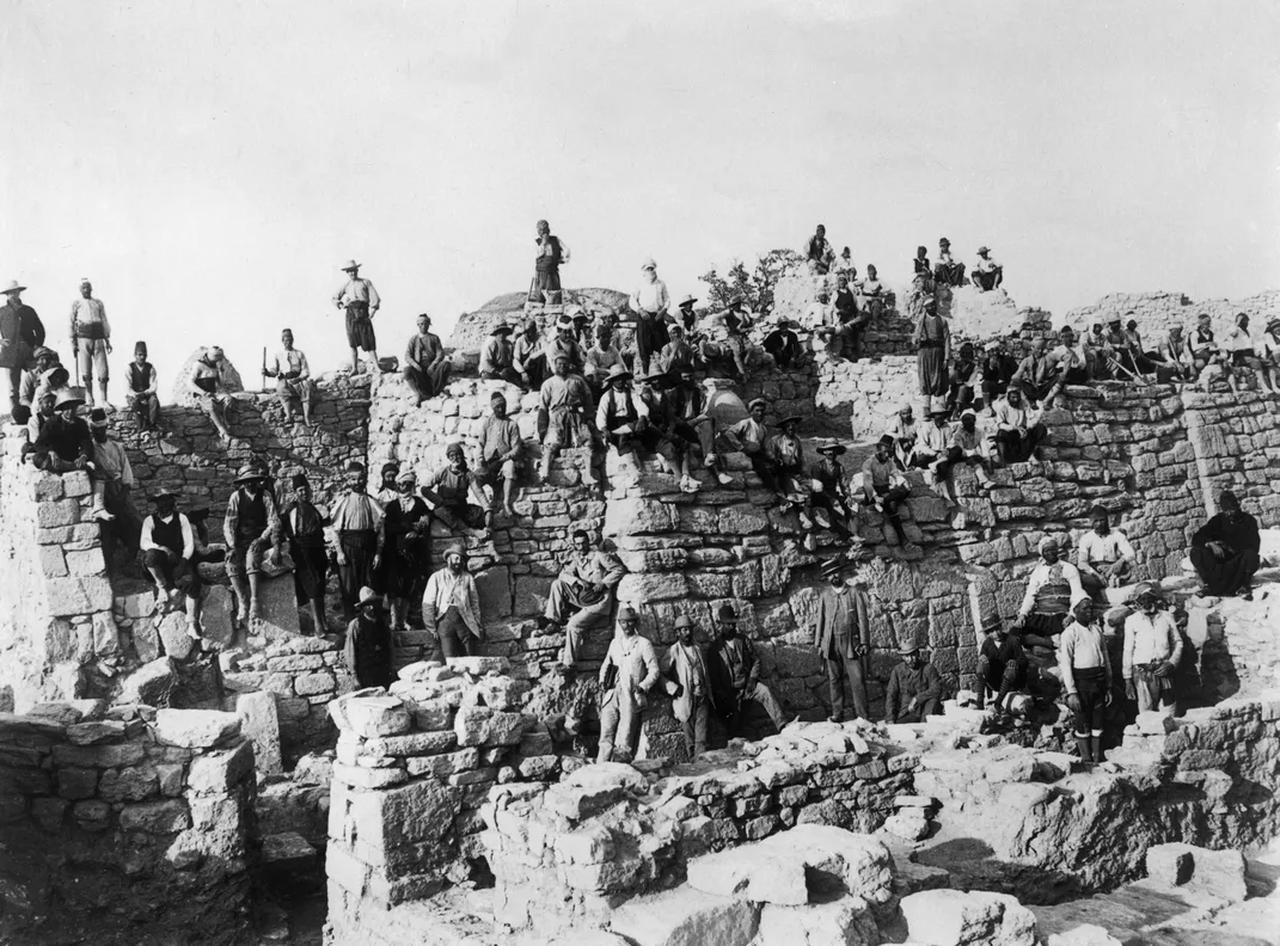

European archaeologists, often backed by state institutions, ventured into Ottoman lands not only to unearth history, but also to assert cultural hegemony. Excavations became entangled in diplomacy. British, French, German, and American officials frequently negotiated excavation permits, using embassies in Istanbul as their base of operations. These artefacts, once uncovered, often found their way to institutions like the British Museum or the Louvre, with diplomatic channels ensuring their exportation.

While foreign archaeologists focused on exporting the past, Ottoman leaders began to recognize the value of protecting and showcasing their own heritage. In 1846, the foundation of the Muze-i Humayun (Imperial Museum) marked the first step in reclaiming cultural authority. Led by figures like Osman Hamdi Bey, the museum soon became a national symbol of Ottoman pride and a soft power instrument in the empire’s diplomatic playbook.

European interest in Ottoman antiquities compelled the government to modernize its cultural policies. Antiquities regulations were introduced in 1869, revised in 1874, and significantly expanded in 1884 and 1906. These regulations asserted Ottoman ownership over all archaeological finds, restricting the free export of artefacts and requiring formal permission for excavation.

The concept of archaeo-diplomacy manifested clearly in the delicate balancing act between granting excavation permits and asserting sovereignty. For instance, the British archaeologist Charles Fellows received permission in the 1830s and 1840s to excavate and export Lycian artefacts. His work was sanctioned at the highest levels, revealing the extent to which the Ottoman administration used such permissions as diplomatic tools.

In another notable example, in 1893, a Christian-themed stone chest unearthed near Afyon was gifted by Sultan Abdulhamid II to Pope Leo XIII—an act of cultural goodwill designed to foster religious and political ties with the Vatican.

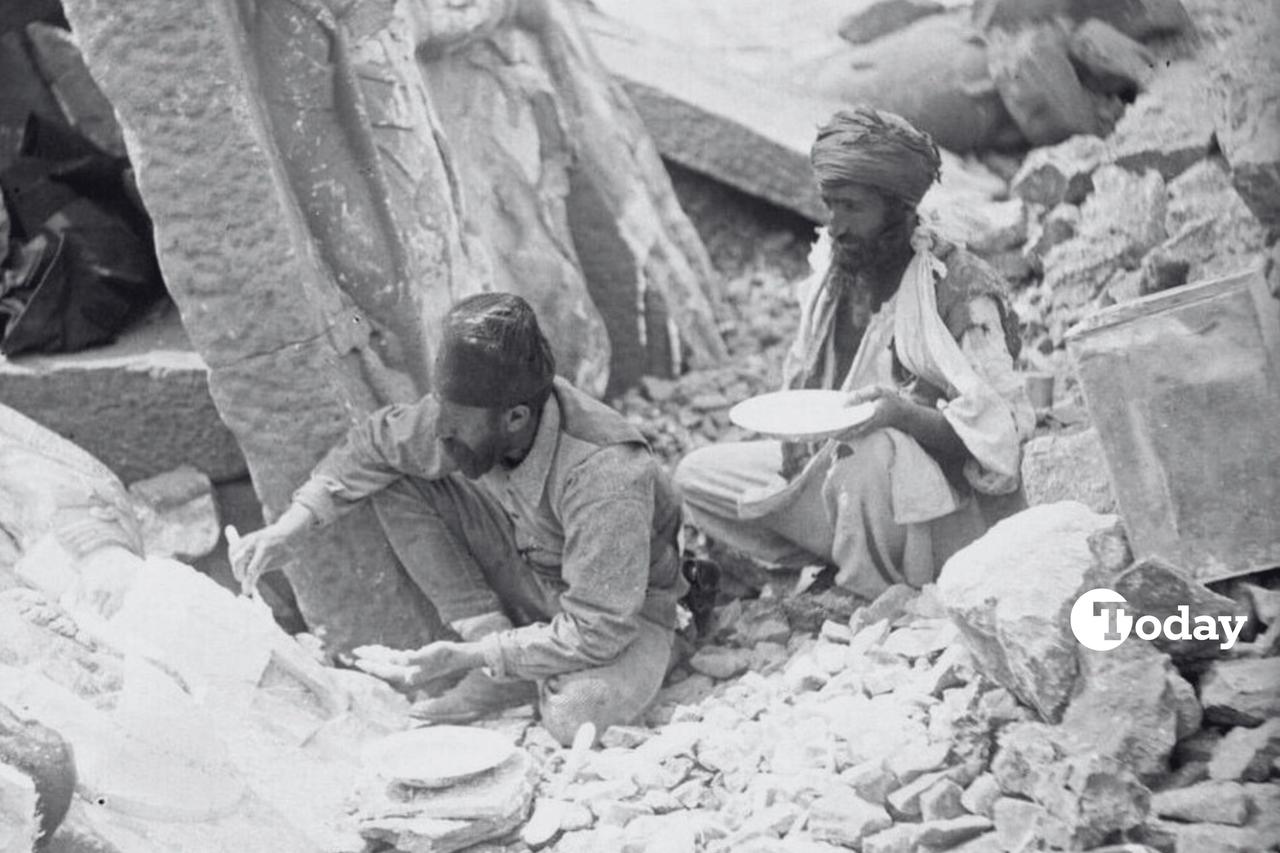

Despite regulatory efforts, smuggling remained rampant. The case of Heinrich Schliemann, who illegally exported artefacts from the site of Troy in 1873, highlighted the limitations of Ottoman enforcement. Nevertheless, the empire fought back through diplomatic protests and legal action to retrieve the stolen heritage.

Under pressure from European encroachment, Ottoman elites re-evaluated their own cultural heritage. Archaeology became more than science; it became politics. The narrative in Ottoman museums subtly shifted to emphasize Hellenistic and Byzantine periods, aligning the empire with European antiquity and distancing it from the orientalist gaze imposed by the West.

By the late 19th century, the Ottoman State had become an active participant in international scholarly gatherings, sending representatives to archaeology and anthropology congresses across Europe.