The Hajj is a significant religious obligation in Islam, mandatory for those who are financially able but not for those who are not.

The Hajj is performed by visiting the Kaaba in the city of Mecca in the Arabian Peninsula (known as the Hejaz), which is considered the House of Allah on Earth and which Allah commanded the Prophet Abraham to build, and by fulfilling the necessary rites.

This region, referred to as the Holy Lands for Muslims, also granted great prestige to Islamic states that controlled it. Being the "Servant of the Holy Lands," a tool for political legitimacy, sometimes created crises that pitted two great Muslim states, such as the Mamluk and Ottoman empires, against each other.

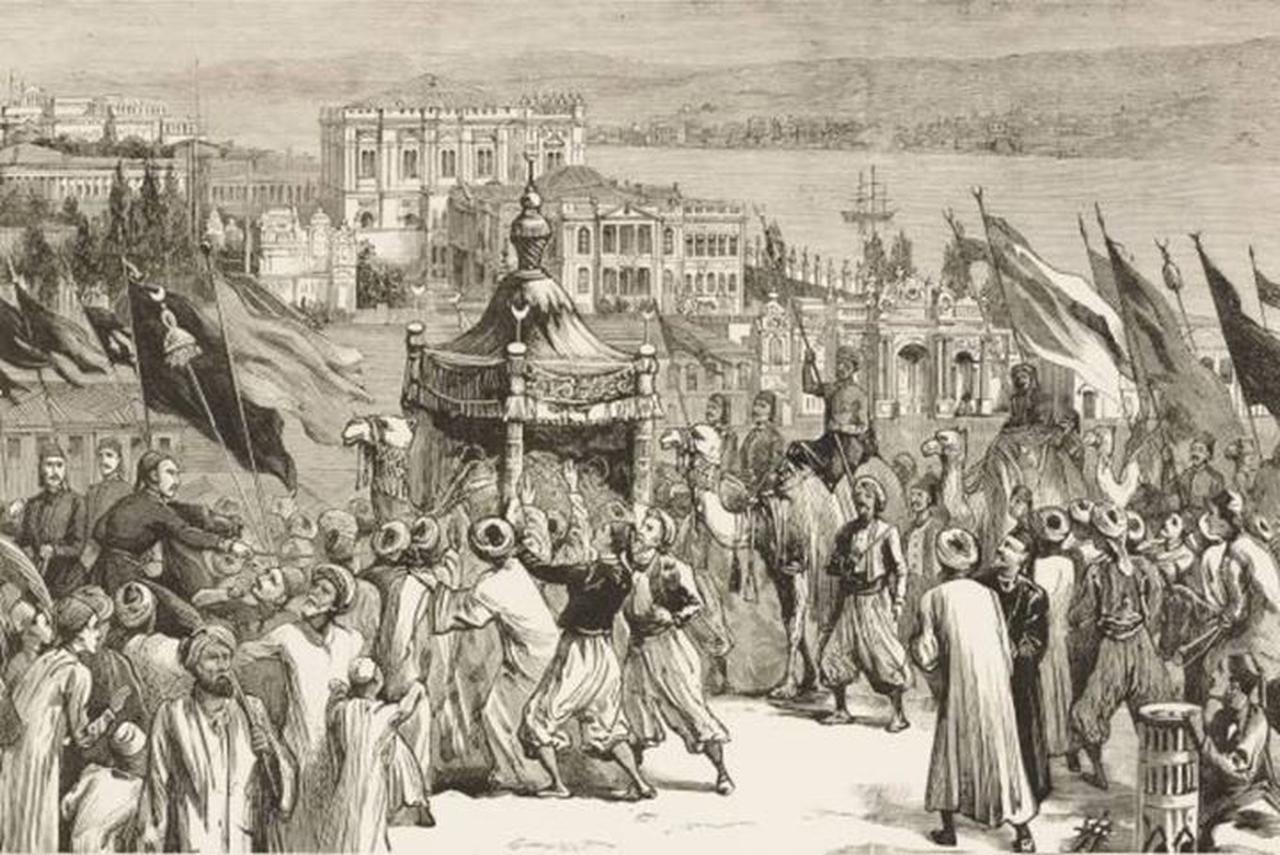

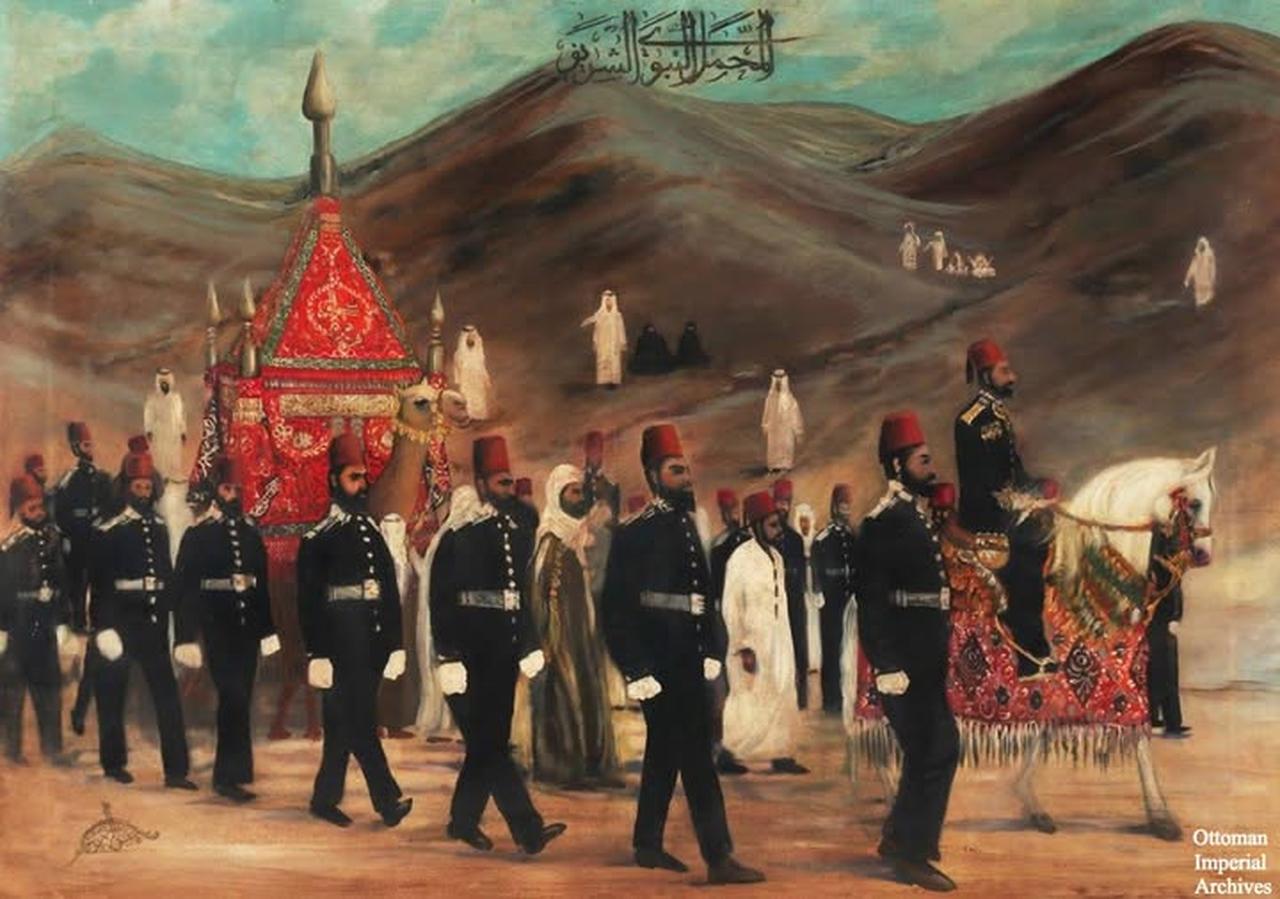

For 400 years, the Ottomans organized the Hajj for the Islamic world. The greatest difficulty they faced during this period was the attacks by Bedouins (nomadic Arabs) living in the Arabian deserts on pilgrim caravans. Ottoman administrators realized that they could not completely resolve this issue by merely stationing soldiers in Hajj caravans.

Therefore, during the Hajj seasons, they would send money and various gifts to the Arab bandits under the name of "urban surresi" (payments to the Bedouins).

However, if the payment to the Bedouins was delayed, attacks on Hajj caravans would begin, resulting in hundreds of pilgrims losing their lives and possessions.

The Ottoman Empire, by occasionally giving gifts to the Bedouins who engaged in banditry in the desert, ensured the security of the Hajj route and its legitimacy in those lands without maintaining a large military force. Negotiations with the Bedouins for the safety of the Hajj route would begin in Damascus immediately after the end of the Hajj season.

The person appointed by the Ottoman administration as the emir-i Hajj (commander of the Hajj caravan) for the following year would conduct these negotiations with the Bedouins. Sometimes hostages would be taken from the Bedouins to guarantee the caravan's security, and sometimes the Bedouins would be asked to accompany the caravan up to a certain point.

Ottoman administrators would even station soldiers and sometimes even cannons in the Hajj caravan to prevent attacks by bandit Arab tribes. Fortresses were also built at certain locations to ensure security.

However, despite all these measures, pilgrim caravans were occasionally robbed, and many pilgrims were killed. These attacks could occur not only on the road but even in Mecca and Medina.

Evliya Celebi, in the 1670s, states that Bedouins attacked pilgrims while they were unarmed and in ihram (pilgrim's ritual garments) in the Masjid al-Haram (i.e., the Kaaba and its surroundings). One of the most interesting Bedouin attacks occurred in 1625.

A Bedouin woman distributed sweets, which she claimed were for a deceased family member but secretly contained a sedative, to the soldiers in the Muazzama Fortress. When the soldiers ate it and fell into a deep sleep, the Bedouins plundered the fortress.

The historian Silahdar Findiklili Mehmed Aga states that during the return from the Hajj in 1691, Bedouins who attacked the caravan martyred many pilgrims, took hundreds hostage, and robbed hundreds more. The Bedouins who attacked the caravan even left elderly women naked.

After the Bedouins left, the pilgrims, ashamed and unsure what to do, covered their private parts with pieces of felt and went, blushing, to the other pilgrims at the next stop. Caravan administrators managed to rescue the hostage pilgrims by paying large sums of money to the Bedouins.

The Bedouins would attack Hajj caravans again if payments were delayed or if they were not satisfied with the surre (meaning "purse," referring to the gold given to the Bedouins) provided to them.

There were even instances where officials serving in the Hajj caravan were given as hostages to guarantee payment to Bedouins who threatened to attack the pilgrim caravan because they had not received their money.

Especially, the refusal of the emir-i Hajjs to pay the Bedouins often led to bloody incidents. In 1701, during the return from the Hajj, thousands of Arab bandits attacked the Hajj caravan. After ten days of conflict, thousands of pilgrims were martyred, thousands were taken hostage, and thousands more died of starvation.

Those who managed to escape arrived in Damascus in a state that could be described as naked. The reason for this Bedouin attack was Emir-i Hajj Hasan Pasha's attitude of "disciplining" the tribes demanding money with the sword. Hasan Pasha, defeated by the Arab bandits, disguised himself and forcibly fled to Damascus, and went down in history as "Hacikirdiran Hasan Pasha" (Hasan Pasha, the Destroyer of the Hajj).

One of the bloodiest attacks on the Hajj caravan occurred in 1757. The Bedouin attacks on the Damascus caravan returning from the Hajj in 1757 caused the deaths of thousands of pilgrims.

During the Ottoman Empire, the Kaaba underwent repairs at various times. During the reign of Murad IV, it was almost entirely rebuilt from scratch. Many facilities and places of worship were constructed in both Mecca and Medina for the comfort of pilgrims.

The Mughals and Persian shahs also wanted to make their mark by building facilities for pilgrims in the Holy Lands.

However, the Ottomans spared no material sacrifice to demonstrate their political legitimacy. For example, Ahmed I had the covering of the Kaaba made of satin, its inscriptions written in gold, and also had gold columns erected at its corners. The Ottoman Empire spent approximately 400,000 gold coins annually on the Hajj organization.

This amount is more than half of what the empire spent in a major war. Moreover, apart from the small amount of customs revenue obtained from Jeddah, no other income flowed into the Ottoman treasury from the Haramayn region.

The only member of the Ottoman dynasty who went on the Hajj was Cem Sultan. During the Ottoman Empire, neither before nor after him did any male member of the Ottoman dynasty perform the Hajj.

After the end of the Empire, the last Ottoman Sultan, Vahdeddin, went on Hajj. However, due to a bandit attack, he had to return after performing Umrah without completing his Hajj. When Cem Sultan took refuge in Egypt, he requested permission from the Mamluk Sultan Qaytbay to go on the Hajj.

Upon the Sultan's approval, the young prince joined the Hajj caravan with his mother and wife. Because Cem Sultan went on Hajj, that year's Hajj caravan was prepared with even more splendor.

Prince Cem visited Mecca and Medina, completed his Hajj, and returned to Cairo in early March 1482.

Why Ottoman sultans did not go on the Hajj has been a debated topic for years. However, one point is often overlooked: male members of the dynasties that ruled pre-Ottoman Turkish states, such as the Ghaznavids, Karakhanids, Great Seljuks, and Seljuks of Rum, also did not go on Hajj.

There was no tradition of ruling families performing the Hajj before the Ottomans. Furthermore, we do not see male members of the ruling families of contemporary Mughal, Safavid, and Afsharid states of Iran performing the Hajj either. Some female members of the dynasties that ruled pre-Ottoman Turkish states and the Mughal Empire did go on the Hajj.

This was also the case for the Ottomans. It is known that some women belonging to the Ottoman dynasty went on the Hajj. These female members represented the Ottoman and other dynasties on the Hajj.

The Ottoman Empire's administrative system did not permit a monarch to be absent from the center for the Hajj journey, which lasted approximately nine months. Before the 19th century, the probability of a sultan undertaking such a journey and losing his throne upon return was quite high.

Additionally, due to two major enemies like Persia and the Habsburgs, the empire needed to remain close to its political center. However, even with improved transportation in the second half of the 19th century, which shortened the Hajj journey, and with the Ottoman monarchy becoming more systemized, the question of why the sultans did not go on Hajj still remains.

During this period, Sultan Abdulaziz traveled to Europe, and Sultan Resad undertook a long trip to the Kosovo region. However, there is no information indicating their intention to perform the Hajj. Instead of going on Hajj themselves, Ottoman sultans sent multiple deputies in their place.

Male princes were also not allowed to go on Hajj due to concerns that they would be out of supervision and might find opportunities for political activity. Since Ottoman women sultans were the representatives of the dynasty least likely to cause political issues, their going was not a problem. Many female members of the dynasty went on the Hajj.

For example, in 1573, Sah Sultan, the daughter of Selim II, represented the Ottoman dynasty on the Hajj. The sultans did not go on Hajj, but their cut hair was taken.

The sultan's hair would be cut by the head barber, washed in a silver basin, then fumigated with incense, placed in a drawer, and given to the caravan carrying the surre. The sealed drawer would be taken to Medina and buried near the tomb of the Prophet Muhammad.