One of Washington’s most prestigious addresses for hosting America’s friends—or those it wishes to be friends with—is Blair House. Wednesday at 6 p.m. local time, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan arrived at this historic residence.

Following the 80th United Nations General Assembly, attention now turns to Thursday’s meeting between Erdogan and President Donald Trump. During his official program, Erdogan will reside at the guesthouse located directly across from the White House—a gesture extended by Trump, as Blair House is reserved for distinguished foreign leaders. Erdogan had previously stayed there in 2013.

This visit, coming on the heels of the UNGA marathon, is not only about bilateral meetings; it also marks a critical juncture in Turkish–American relations, which reached their lowest point under the Biden administration and now appear poised to regain a foundation of partnership under Trump’s second term.

Only a select few, such as Vladimir Putin and Erdogan, have been granted what one might call an “equal but privileged” status in Trump’s diplomacy. This pattern underscores the strategic significance of Erdogan in U.S. foreign policy and highlights the Turkish president’s skill in high-level leader diplomacy.

Blair House as a symbol of diplomacy

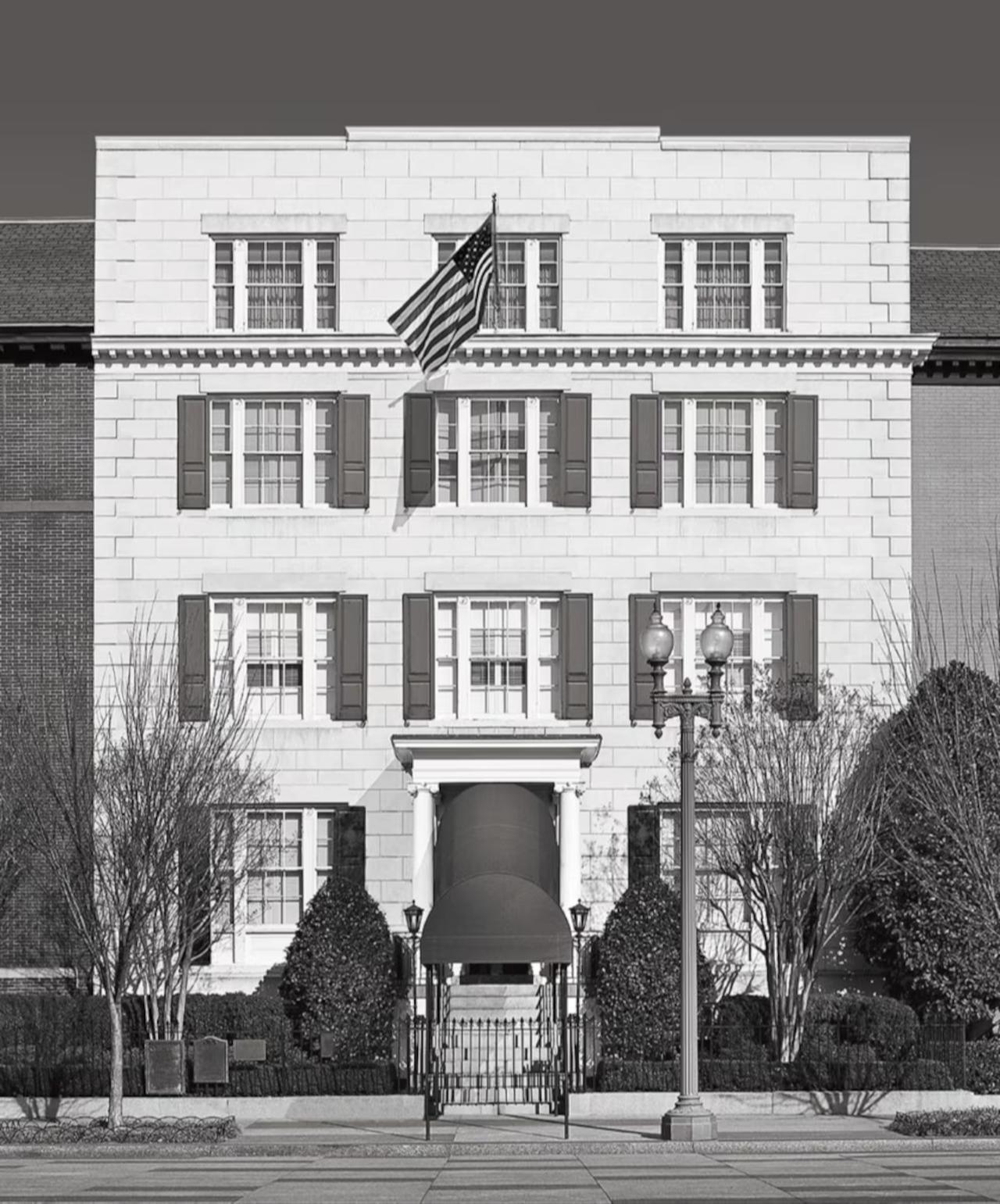

Blair House’s symbolic power is crucial in this context. It is not just a guesthouse; it is a diplomatic barometer indicating which leaders the American president regards as close allies. Situated directly across from the White House, it has hosted an array of historic figures—from Queen Elizabeth II to Charles de Gaulle, from Nelson Mandela to Putin. During a foreign leader’s stay, that country’s flag flies proudly outside the residence. And the decision of who is invited rests entirely with the American president. Raymond Martinez, a former protocol official, summed up the selection process perfectly: “You don’t invite everyone to your home. They are either close friends or people you want to grow closer to. Blair House’s guest list reflects that.”

For Türkiye, Blair House carries a unique story. The first Turkish leader to visit the United States officially, President Celal Bayar, was also the first to stay at Blair House. In January 1954, after arriving in Washington aboard the trans-Atlantic vessel Mauritania, Bayar spent a night at the White House as a guest of President Dwight Eisenhower and then moved to Blair House for the remainder of his visit. That visit symbolized the peak of Türkiye’s post-NATO accession ties with the United States.

Blair House, directly across from the White House, is at the heart of American diplomacy. Built in 1824, it was first the home of a military doctor and later of journalist and politician Francis Preston Blair. Since its official opening as a guesthouse in 1942 under President Roosevelt, it has hosted heads of state and government from around the world, becoming a living repository of diplomatic memory. From Lincoln’s writing desk to the wallpaper chosen by Jacqueline Kennedy, every detail offers visitors not just comfort but a tangible connection to history. The residence is not merely a place to sleep; it embodies status, respect, and diplomatic intimacy.

Historical Turkish visits to Blair House crucial

Stories of Turkish leaders at Blair House add another layer of meaning. In 1954, Celal Bayar became the first Turkish leader to step inside. Against the backdrop of the Cold War, his visit symbolized Türkiye’s strengthening ties to the Western alliance. Hosted initially by President Eisenhower at the White House and then in the grand halls of Blair House, Bayar’s stay was more than a diplomatic courtesy—it was a testament to Türkiye’s NATO role and its place in the Western bloc.

In 1964, another memorable visit occurred under different circumstances. President Ismet Inonu stayed at Blair House as the guest of President Lyndon Johnson during one of the tensest periods in Turkish–American relations, just before the Johnson Letter. Sharing the residence at the same time was the Greek Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou. Years later, Papandreou’s wife, Margarita, recounted a small, human anecdote: In the suite, Inonu opened a closet and found a scarf and gloves belonging to Mrs. Inonu. “How I wished I could take these to Türkiye and hand them to her myself,” she said. Papandreou’s reply captured the delicate balance of diplomacy: “Not today, perhaps in the future.” Such small, human moments reside alongside the larger, more serious entries in Blair House’s memory.

By the late 1980s, during Kenan Evren’s 1988 visit to Washington, Blair House became a point of contention. The White House cited renovations as the reason Evren could not stay there. While technically true, the explanation was met with skepticism in Türkiye. The renovations were complete, yet the doors remained closed—a reminder that even the building itself can convey diplomatic messages. Evren’s exclusion subtly reflected Türkiye’s post-coup image on the international stage.

Turgut Ozal often chose a different path. Though visiting Washington almost annually, he preferred the familiar Madison Hotel over Blair House. Yet his 1991 meeting with George H. Bush at Camp David, intimate and informal, overshadowed even Blair House. That encounter captured the spirit of liberal economic alignment and support during the Gulf War, marking a distinctive moment in Turkish–American relations.

In 1993, Tansu Ciller added an unusual note to Blair House’s history. Official programs concluded, and she was expected to move to her hotel, yet she had grown so fond of the residence that she refused to leave. The White House could not simply tell a prime minister to depart. Ciller stayed for three additional days—an anecdote highlighting both the magnetism of the house and Türkiye’s efforts to assert itself in the 1990s foreign policy.

Buuent Ecevit’s 1999 visit brought yet another challenge. World Bank and IMF officials refused to attend at Blair House, even though protocol required meetings with guest leaders to occur there. The impasse turned into a minor diplomatic incident but was ultimately resolved, and the meetings proceeded as planned. At the time, Türkiye’s agenda included economic crises and the fight against the PKK terrorist group; in Blair House’s salons, the issues and the setting itself were equally at the table.

Abdullah Gul’s 2008 visit highlighted a period of confidence in Turkish–American relations, emphasizing trust. Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s 2017 stay, in turn, symbolized a modern strategic partnership.

Historic guestbook of Blair House

Blair House’s guestbook records all of these visits, from Mandela to Queen Elizabeth, from Netanyahu to Inonu. Some left serious diplomatic messages, others small jokes or tokens—a forgotten scarf or gloves—that nonetheless became part of history.

Today, Blair House remains more than a guesthouse; it is where diplomatic rituals, strategic negotiations, and human anecdotes converge. From Celal Bayar’s Cold War footsteps to Inonu’s gloves, Ozal’s Camp David encounter, Ciller’s stubbornness, Ecevit’s protocol challenges, and Gul and Erdogan’s modern chapters, the corridors of Blair House echo not just American but Turkish diplomacy.

And these are only some of the Turkish leaders who stayed there. Cevdet Sunay in 1967, Nihat Erim in 1972, Suleyman Demirel in 1992—each visit reflected the geopolitical and domestic circumstances of their times. Sunay’s tenure coincided with the Vietnam War and Cyprus tensions; Erim’s with the aftermath of the 1971 memorandum; Demirel’s with the end of the Cold War and the new security order. Adnan Menderes visited in 1954, symbolizing Türkiye’s opening to the West during the Democrat Party era. Mesut Yilmaz stayed at the Willard Hotel in 1997 rather than Blair House, during a period dominated by discussions on the PKK and human rights. Abdullah Gul visited in 2008, a time defined by Iraq and broader Middle East policies, while Ahmet Necdet Sezer never made the trip to Washington.