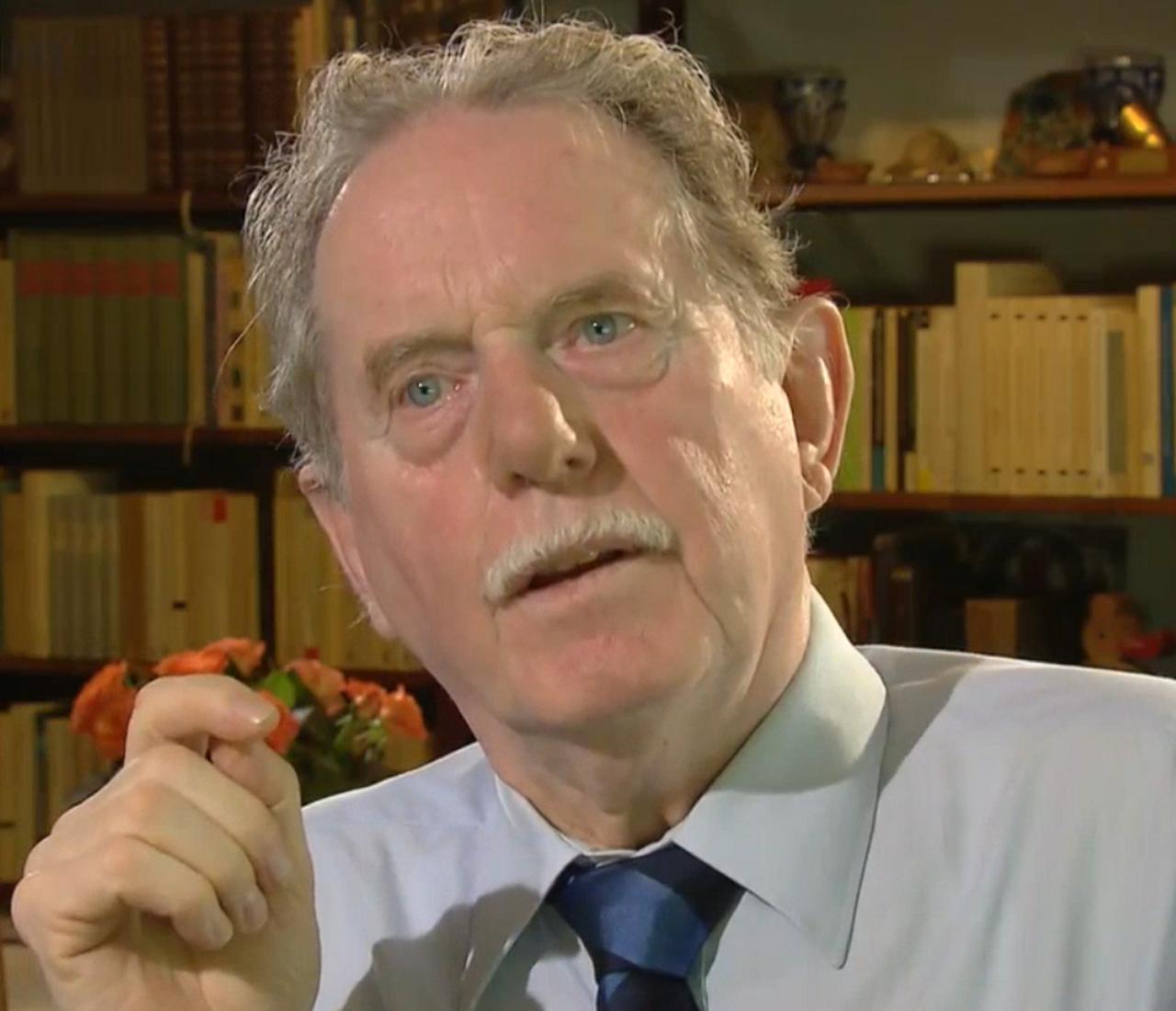

All great stories begin with a journey with either a person setting out on the road, or a stranger arriving in town. For Professor Machiel Kiel, that journey began with a passion for the hidden histories of the Ottoman Balkans. Over more than five decades, he set out on a tireless quest travelling through remote villages, ancient bazaars, and crumbling mosques to uncover stories long forgotten to preserve the architectural soul of a region shaped by centuries of empire.

His work was not simply about buildings; it was about the people, cultures, and histories intertwined within every stone. Through meticulous field research, groundbreaking scholarship, and an unrivaled photographic archive, Kiel brought to life the vibrant legacy of Ottoman architecture in Southeast Europe, rescuing it from neglect and oblivion.

As the guardian of this rich heritage, Professor Kiel’s contributions have become an indispensable foundation for historians, architects, and preservationists worldwide. His journey reminds us that history is not static; it is a living narrative waiting to be rediscovered.

Machiel Kiel’s journey into Ottoman history and architecture was not a simple academic pursuit but a calling that shaped his entire life. His extensive research focused on the Balkan Peninsula, a crossroads of cultures where Ottoman, Byzantine, Slavic, and Western influences converged in a unique architectural and cultural tapestry.

Long before the convenience of digital technology, he traveled extensively across the Balkans, from the bustling streets of Skopje to the quiet corners of Prizren and Bitola. With camera and notebook in hand, he documented countless mosques, bridges, caravanserais, and baths many in states of decay or threatened by modernization.

One of his earliest significant achievements was the detailed study of the Old Bazaar in Skopje before the catastrophic earthquake of 1963. His documentation preserved the memory of buildings that were later lost or severely damaged, making his records invaluable to historians and conservationists alike.

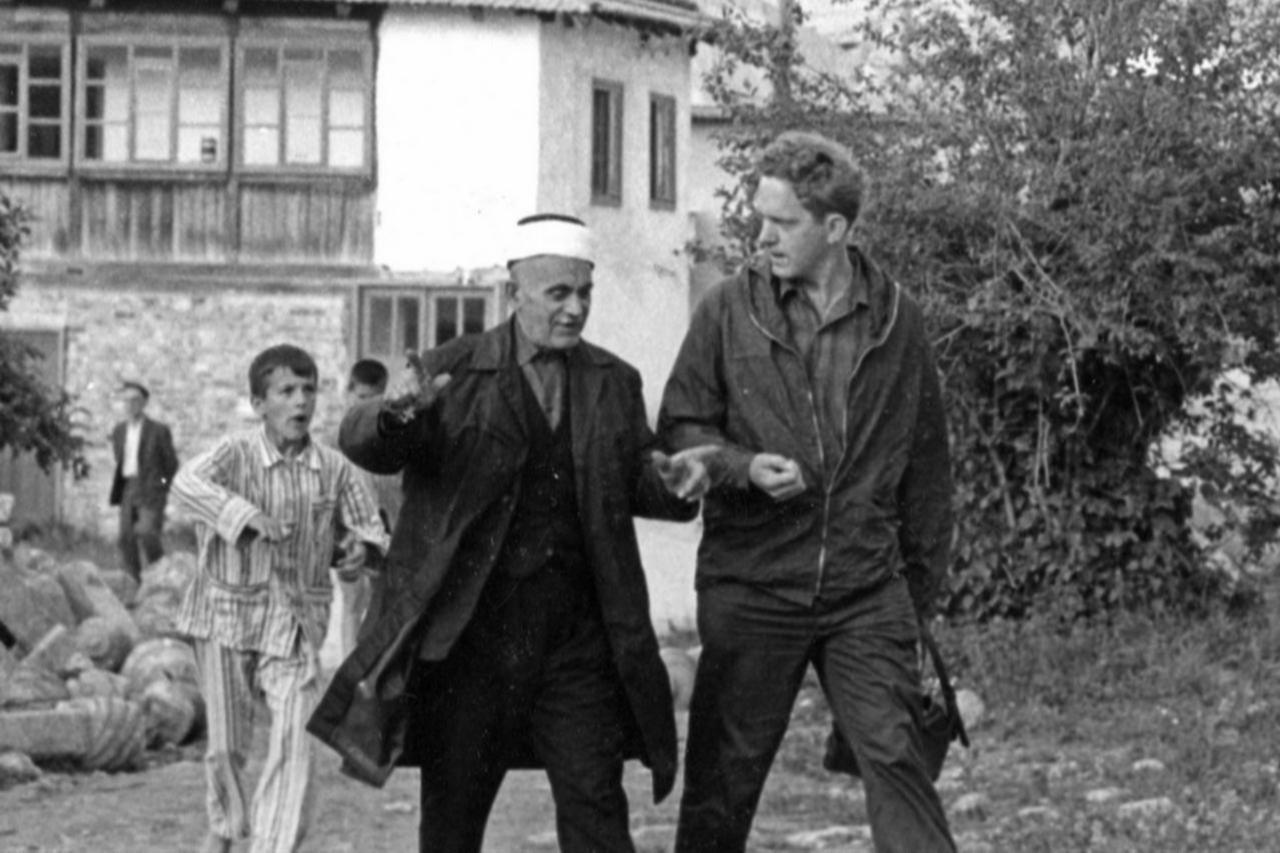

Kiel’s fascination with the Balkans began long before he became a renowned scholar. In 1959, as a young idealist, he traveled with friends to a devastated village in Greece to build a free water supply and school. This hands-on experience introduced him to the region’s people and landscapes, sparking a lifelong commitment.

On this journey, Kiel visited key cities such as Skopje, Nis, Prizren, Bitola, and Belgrade, gathering photographs and data that would form the basis of his future research. He also began learning Turkish, opening doors to Ottoman archives and local sources.

Despite not having completed traditional schooling, Kiel leveraged a unique Dutch opportunity allowing multilingual individuals to take university entrance exams without formal middle or high school education. Seizing this chance, he studied diligently, passed the exam, and enrolled at the University of Amsterdam, where he earned his doctorate.

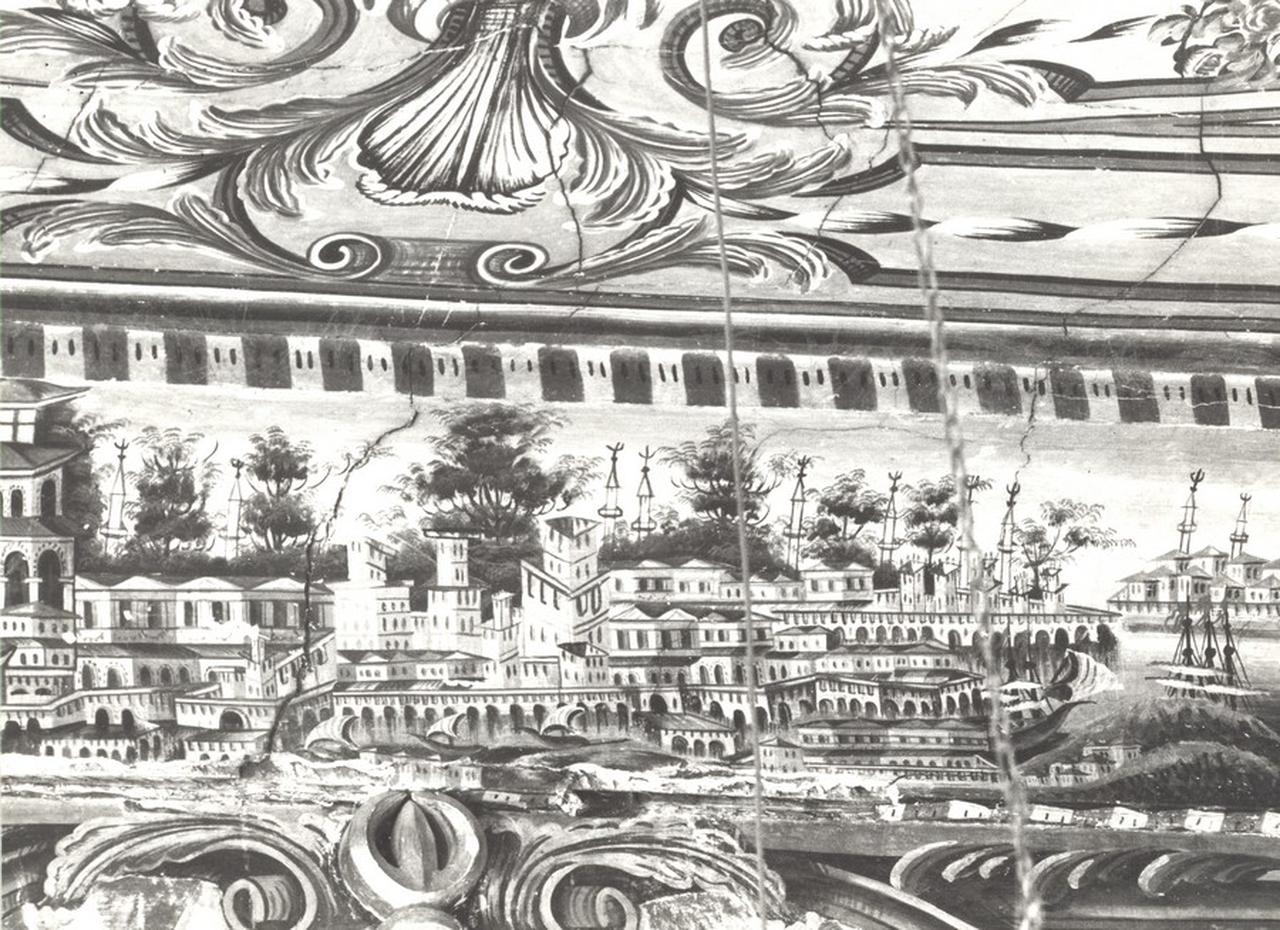

Beyond words, his legacy lives on his visual archive. This collection, now preserved at the Netherlands Institute in Türkiye, contains thousands of images of Ottoman monuments scattered throughout the Balkans. Many of these buildings no longer exist, due to neglect, or redevelopment.

The archive serves as a visual time capsule, supporting restoration projects and scholarly research worldwide. Through his lens, Kiel captured the beauty, complexity, and fragility of a cultural heritage that spans centuries.

Born in the Netherlands, he was raised with Dutch but soon developed a hunger for languages that reflected his expanding intellectual and geographical interests. He became fluent in German, English, and French 'essential tools for engaging with both Western European academia'.

But it was his mastery of Turkish, Serbian, and Bulgarian that truly distinguished his work in Ottoman studies.

These regional languages opened doors that would remain closed to most foreign researchers. They allowed him to dive deep into Ottoman-era cadastral registers (tahrir defterleri), endowment deeds (vakfiye), architectural plans, and local chronicles stored in dusty municipal archives and private collections.

His fluency enabled him to decipher handwritten Ottoman script as well as modern documents, and—equally importantly—it allowed him to build long-lasting relationships with local historians, imams, archivists, and villagers who became indispensable collaborators in his fieldwork.

Through language, Kiel didn’t just gain access to sources—he gained trust. In communities that had experienced war, regime change, and political suspicion, he was not viewed as a distant foreign scholar but as a respectful guest and a sincere student of their shared past. His willingness to learn, listen, and engage with people in their native tongues allowed him to collect oral histories, clarify local architectural knowledge, and retrieve invaluable anecdotal evidence that would never appear in formal archives.

Among his most influential works is Studies on the Ottoman Architecture of the Balkans, a landmark publication that brings together decades of field research and archival analysis. The book is not merely a survey of buildings; it is a cultural cartography of the Ottoman world as it unfolded across Greece, North Macedonia, Albania, Serbia, Bosnia, Bulgaria, and Romania.

It highlights the nuanced relationship between architecture and identity, and offers a counter-narrative to nationalist histories that had long ignored or downplayed the Ottoman past.

Sadly Professor Machiel Kiel passed away on July 29, 2025, leaving behind an extraordinary legacy. His life’s work preserved a critical chapter of Balkan and Ottoman history, transforming it from forgotten ruins into living memory.