A bioarchaeological study has likely pinpointed a rare infant bone disorder in the skeleton of a child aged about 2.5–3.5 years, buried in the Middle Byzantine Tetrapylon Cemetery at Aphrodisias in southwestern Türkiye.

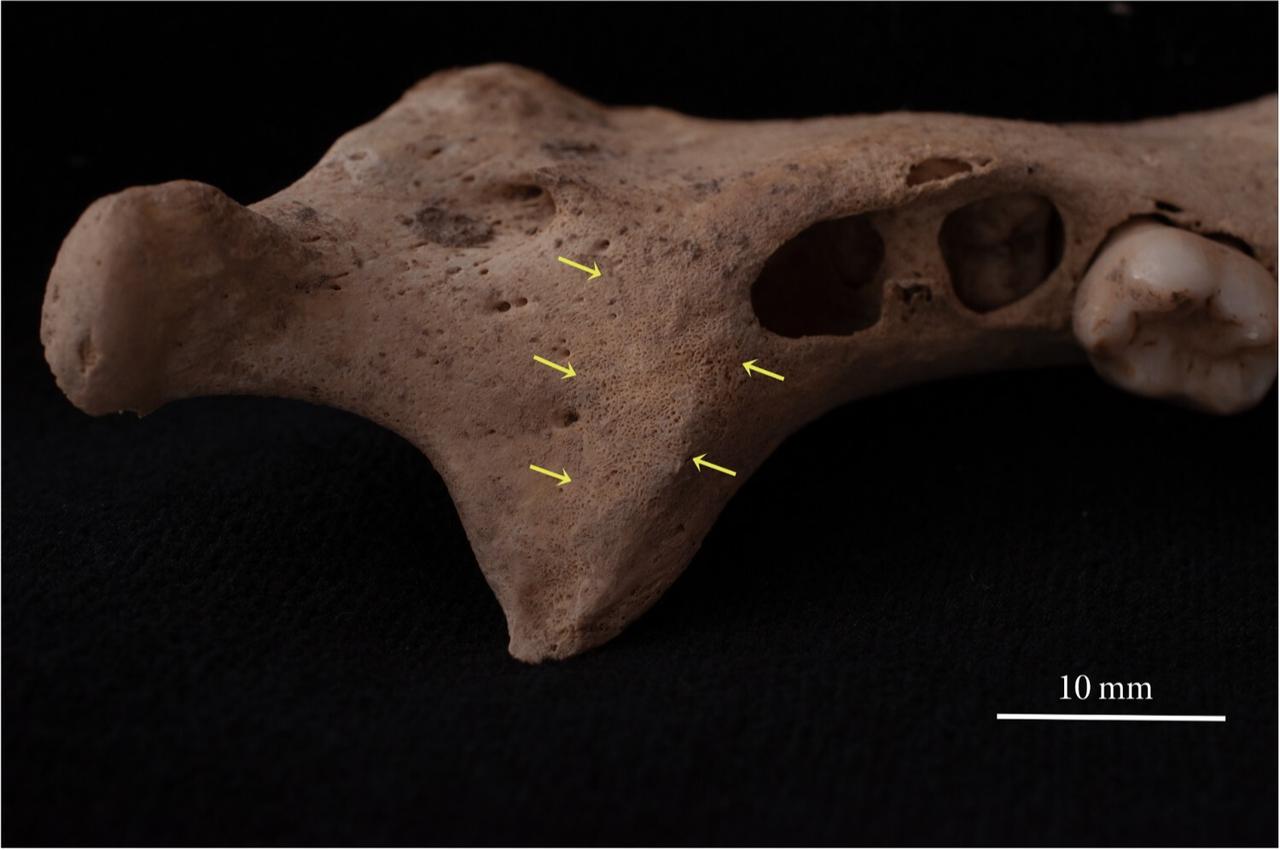

The analysis links the striking, uneven thickening of several bones—especially the left ulna—to infantile cortical hyperostosis (ICH), a self-limiting inflammatory condition of early infancy also known as Caffey disease.

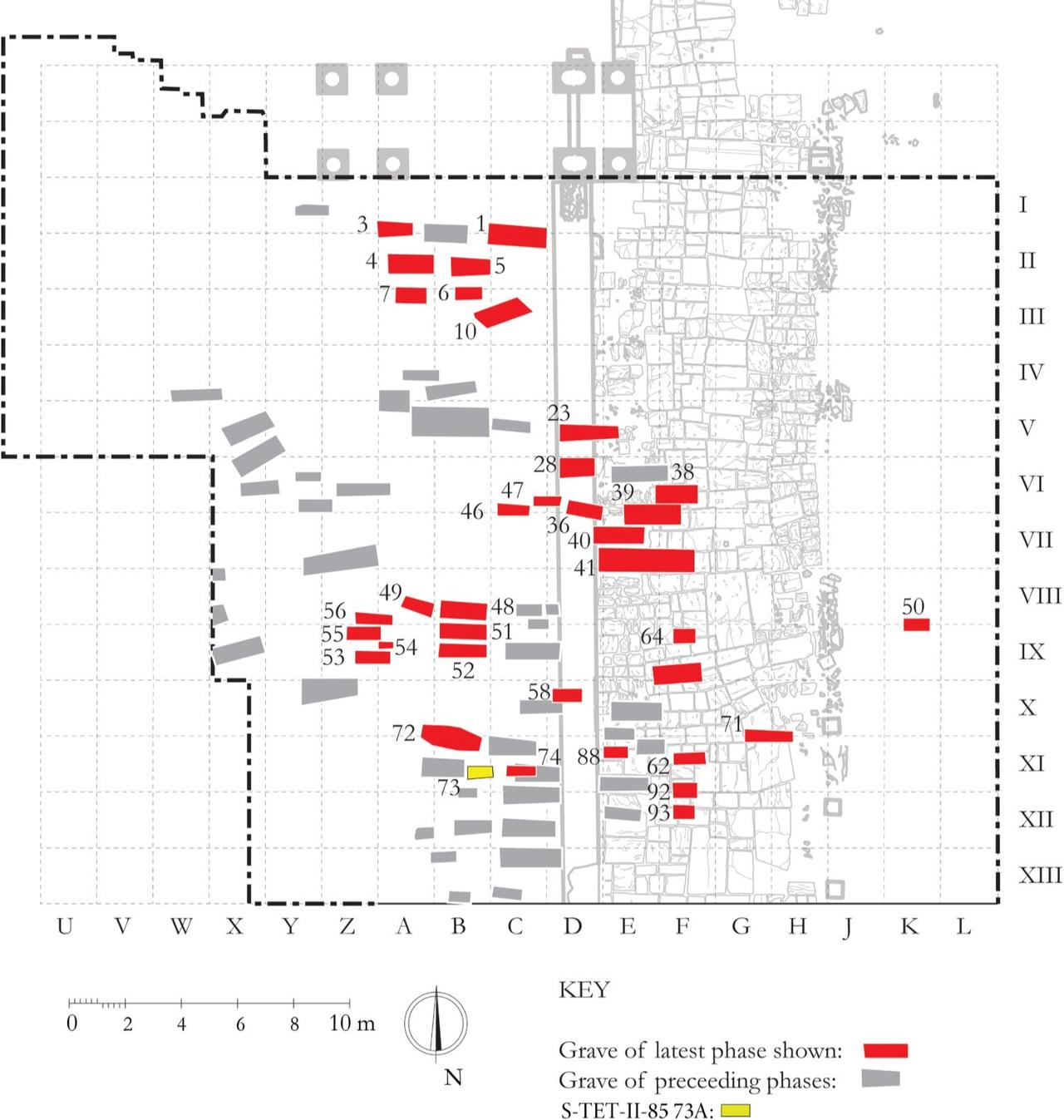

Excavated in 1985, “Tomb 73A” held two non-adults; the individual labeled 73A showed unusual swelling and new bone growth on the jaw, shoulder blade, and forearm and upper-arm shafts.

The cemetery dates to the 10th–12th centuries, placing the case squarely in the Middle Byzantine period in Aphrodisias.

The team noted that the left ulna had enlarged to nearly twice its usual diameter for a child of that age.

ICH (Caffey disease) typically appears around five months after birth, can start at birth or even in utero, and usually settles by about age three, sometimes with rare recurrences.

It is marked by periosteal inflammation—meaning the membrane that covers bones, called the periosteum, becomes inflamed—leading the body to lay down new layers of bone and create visible thickening.

The jaw, ulna, tibia, clavicle, scapula, and ribs are often involved, and the pattern is commonly asymmetrical rather than evenly spread across both sides of the body.

To sort out the cause, the researcher compared the child’s pattern of changes to conditions often seen in skeletal remains—hemolytic anemias, scurvy, rickets, tuberculosis, trauma, or child abuse—and found that key features did not line up.

The absence of typical changes at the ends of long bones, the lack of lytic (bone-destroying) lesions, and the clear, uneven distribution of new bone supported ICH as the closest match.

The child’s teeth pointed to an age of roughly 2.5–3.5 years, while long-bone lengths suggested 1.5–2 years.

Bones can lag when illness or nutritional stress enters the picture, and because ICH often affects the jaw—making feeding hard—the mismatch may not be surprising.

The skeletal changes also showed signs of remodeling, hinting that the child had begun to recover before death.

Cases of ICH are rarely recognized in archaeological contexts because the condition can resolve and leave little trace.

This probable Aphrodisias example, described as the first archaeological case identified in Türkiye, adds to a small but growing record that helps researchers fine-tune how they diagnose transient childhood diseases in the past.

As the author put it regarding the cause of death: “Unfortunately, the cause of death cannot be determined… It is possible that the individual passed away from ICH, complications that arose from ICH, or a completely unrelated matter.”