A previously unpublished stone inscription discovered in southern Kazakhstan is now reshaping what is known about early Oghuz history and the use of writing before the medieval period. Identified in August 2025 at a small local museum in the village of Orangay, near the city of Turkistan, the find provides rare physical evidence that the Oghuz people were already using a written language centuries before Oghuz Turkish began to be written in the Arabic script.

The discovery was formally introduced to the academic community in a research article published on Dec. 21 in YAZIT Journal of Cultural Sciences by Associate Professor Hayrettin Ihsan Erkoc, where scholars presented the inscription as a new and previously undocumented find related to early Oghuz writing practices.

The inscription was identified by two researchers during fieldwork carried out in the historical Oghuz homeland. The stone was being kept at a modest school museum located inside the Mukhtar Awezov Middle School in Orangay, a village in the Sawran district of the Turkistan region of Kazakhstan. The artifact had not previously been the subject of any academic publication.

According to information recorded at the museum and confirmed by local staff, the stone originally came from Kultobe, an ancient Oghuz settlement located within the village. It was reportedly found in the 1990s or early 2000s after an illegal excavation, then handed over to the museum by local residents. The artifact has been registered in the museum inventory since 2003.

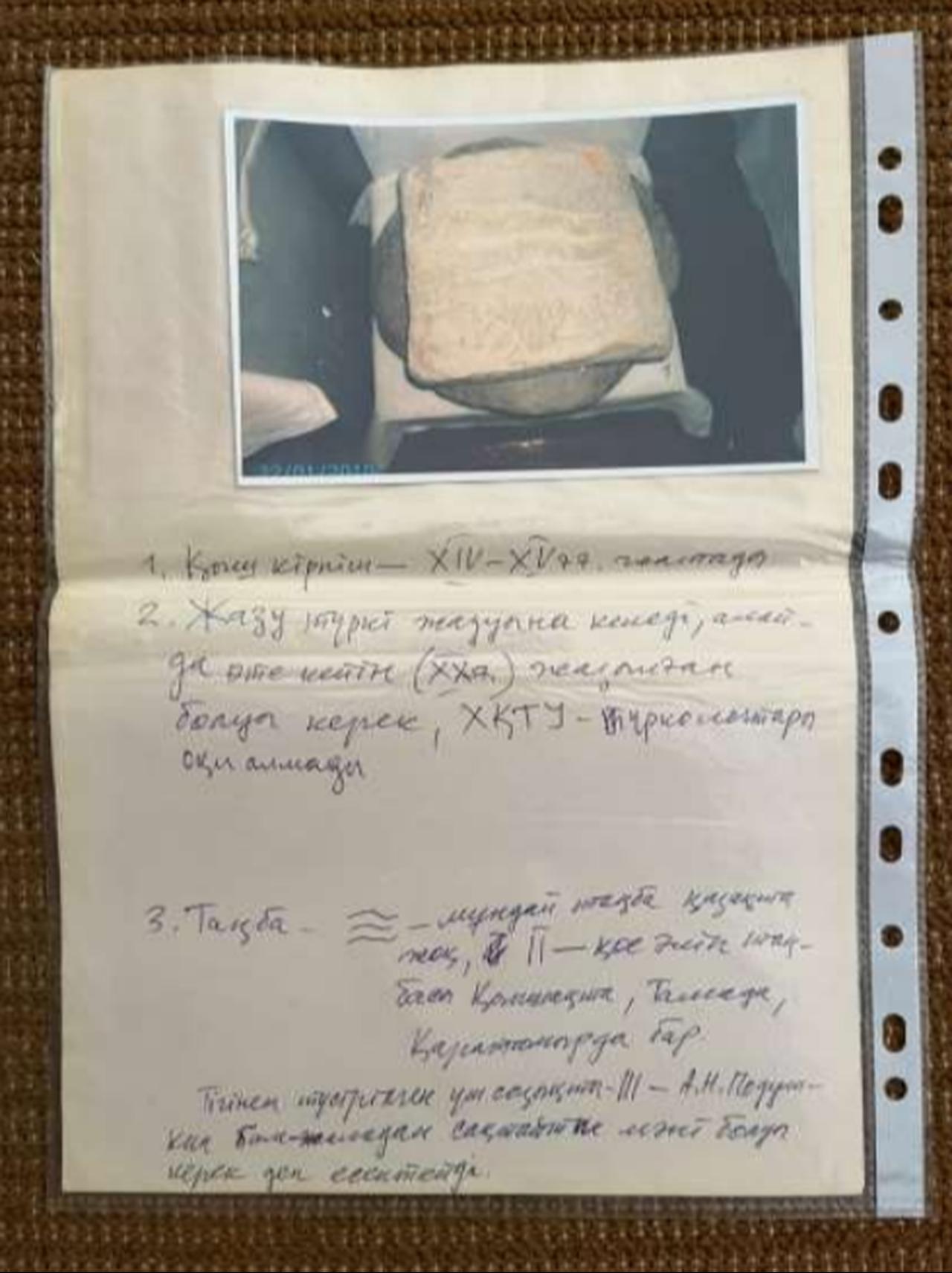

The inscription consists of a single line carved into a square limestone slab measuring roughly 25 by 25 centimeters. Beneath the line of text appears a symbol made up of three wavy lines, which researchers interpret either as a tribal mark, known as a tamgha, or as a stylized representation of a watercourse.

The text is written in what scholars call the Turkic Script, a writing system also known internationally as Old Turkic or runiform Turkic. The line contains seven characters, some of which appear in unusual or rare variants, making interpretation difficult. Because of this, the researchers have put forward two possible readings rather than a single definitive solution.

One proposed reading separates the text into multiple words, while another suggests it represents a personal or political designation, possibly connected with the Khazar Khaganate. The researchers stress that these readings remain hypothetical and require further comparative study.

Scientific observation shows that the stone is made of dolomitic limestone common to the region between the Syr Darya River, known historically as the Seyhun, and the Karachuk Mountains. This suggests the slab was produced locally rather than transported from elsewhere.

The letters were carved using a pointed chisel, while the symbol beneath them appears to have been made with a blunter tool. Weathering patterns indicate that the stone remained outdoors for some time but was not submerged in water for long periods, which helps explain why the inscription remains largely legible.

The three wavy lines under the inscription do not exactly match any known tribal tamghas recorded in medieval sources. However, similar motifs appear in early Turkic and Oghuz contexts, and comparable symbols are known from historical lists of tribal marks preserved in Chinese and Islamic sources.

Researchers also note that the symbol resembles flowing water, a detail that may be significant given the settlement’s proximity to a stream and its broader location near the Syr Darya basin. While the symbol is most likely a tribal marker, its precise meaning remains unresolved.

Based on archaeological context, regional history, and comparisons with other inscriptions found in southern Kazakhstan, the Kultobe inscription is dated to between the ninth and tenth centuries. This period corresponds to the early appearance of the Oghuz in historical sources and predates the adoption of the Arabic script for Oghuz Turkish by several centuries.

Other Turkic inscriptions found around Turkistan support the view that Oghuz was already functioning as a written language long before the 13th century, when Oghuz Turkish began to be widely recorded in Arabic letters in Anatolia and surrounding regions.

The Kultobe inscription offers rare and tangible evidence that early Oghuz communities were not only politically and culturally active but also literate in the Turkic Script. For international readers, the Oghuz were a major Turkic confederation whose descendants played a central role in the formation of Seljuk, Ottoman, and several modern Turkic societies, including in Türkiye.

Although the text itself is short and its interpretation remains open, the find strengthens the archaeological basis for understanding early Oghuz identity and literacy. It also highlights the importance of small local museums, where significant artifacts can remain unnoticed for years.