Archaeologists have uncovered an intricate network of water tunnels carved into soft limestone beneath the Bet She’an Valley in northern Israel, shedding light on how the Mamluk Empire once turned arid landscapes into centers of sugar production — and how this same infrastructure later powered Ottoman flour mills.

The research, published in Water History by Amos Frumkin and colleagues from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Bar-Ilan University, and the Israel Cave Research Center, highlights the sophisticated hydraulic engineering of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The study demonstrates how the Mamluks adapted advanced water technologies to local geological conditions, repurposing brackish water for industry rather than irrigation — an innovation that extended its usefulness into the Ottoman period.

The Mamluks, a military dynasty ruling from Cairo between the mid-13th and early 16th centuries, built their power on control over strategic water systems. In regions like the southern Levant — where rivers were scarce and rainfall unreliable — they developed underground tunnels, aqueducts, and cisterns to drive mills, irrigate crops, and sustain growing urban populations.

Historical accounts record that rulers such as Sultan Qaitbay invested heavily in irrigation and water-powered industries, turning water into a political and economic instrument. As co-author Dr. Azriel Yechezkel notes, this infrastructure “was as much about governance and control as it was about engineering.”

Sugarcane, introduced after early Islamic conquests, quickly became one of the Levant’s most profitable crops. The Jordan Valley, and particularly the Bet She’an area, evolved into a major sugarcane hub, with production sites rivaling those in Beirut and Tripoli.

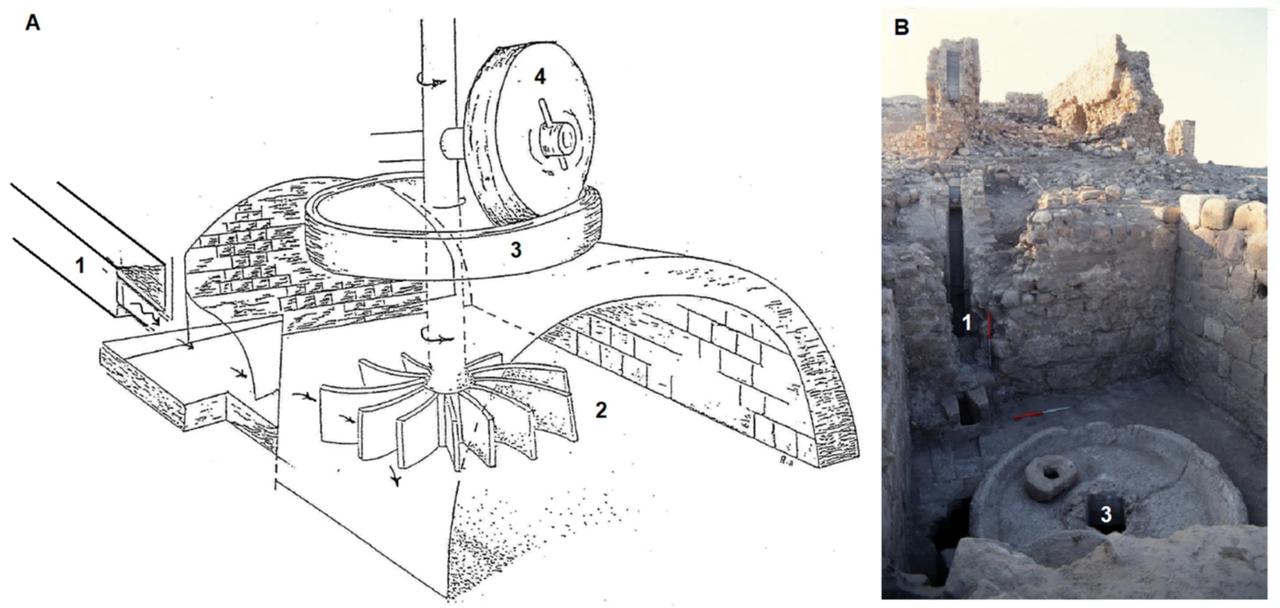

Mamluk engineers diverted perennial springs through tunnels instead of open aqueducts, channeling the water to mills that crushed sugarcane between two stones powered by horizontal paddle wheels. The study’s uranium–thorium dating of mineral deposits inside the tunnels places their construction squarely in the Mamluk period — around the 14th or 15th century.

The research team believes the tunnels near Nahal ‘Amal served as conduits to sugar mills located along the stream, where the high salinity of the water made it unsuitable for drinking but ideal for industrial use. “The brackish flow that could not nourish crops instead nourished commerce,” the authors write.

Archaeological surveys show that many of the Mamluk-era sugar mills were later converted into flour mills under Ottoman rule, which extended across the region from 1516 until World War I. This transition reveals how industrial landscapes evolved while maintaining their hydraulic foundations.

In Bet She’an, Ottoman builders reused the same water tunnels and millstones, adapting the once-lucrative sugar industry to new agricultural realities. By the nineteenth century, local farmers continued to rely on these centuries-old water channels to grind grain and operate small workshops — a testament to the enduring legacy of Mamluk innovation.

The tunnels, up to 45 meters long, were carved through soft tufa rock, a form of porous limestone that was easy to cut yet strong enough to channel water under pressure. Their design allowed water to flow through the network with a controlled gradient, preventing erosion and ensuring steady mechanical power.

Researchers emphasize that such subterranean systems, often overshadowed by monumental aqueducts and dams, were critical to medieval economies. “The true story of water technology,” the study concludes, “lies as much in these hidden tunnels as in the grand architecture above ground.”

The study reveals not only the technical ingenuity of the Mamluks but also a remarkable continuity of industrial heritage under Ottoman rule. The same water that once powered the sugar mills of a medieval empire later drove Ottoman flour production — connecting two dynasties through a shared mastery of hydraulic engineering.

This continuity underscores the importance of looking beyond surface-level ruins. Beneath the tranquil waters of the Bet She’an Valley lies a living record of how Middle Eastern empires sustained trade, agriculture, and urban life through the creative management of one precious resource: water.