A recent study led by Alan Williams and Benjamin Roberts from Durham University has claimed that tin from south-west Britain was widely traded with ancient civilizations in the Eastern Mediterranean around 3,300 years ago.

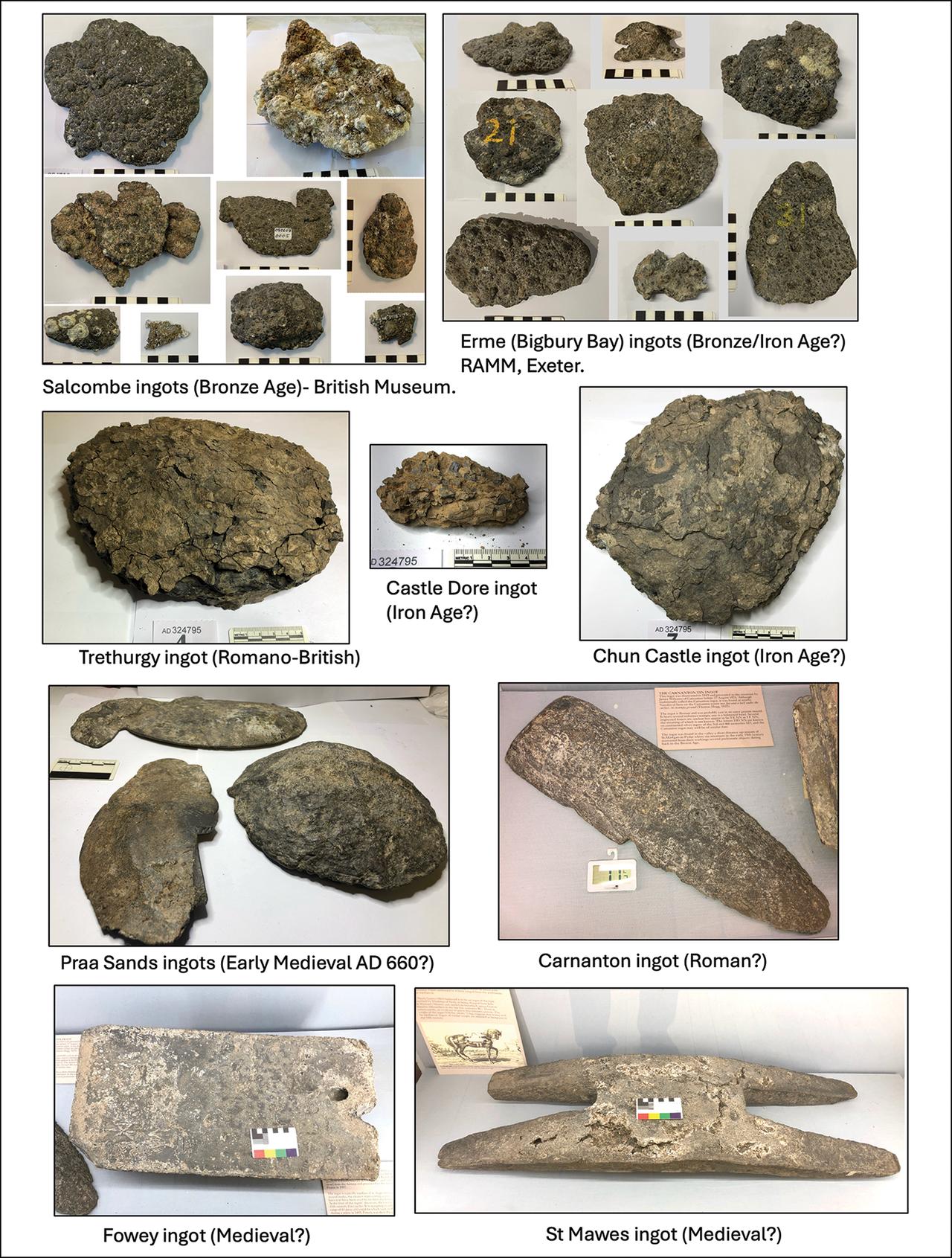

The study’s findings, published in the journal Antiquity, are based on chemical and isotope analyses of tin ingots recovered from shipwrecks off the coasts of Israel and France. According to the researchers, these ingots match the geological signatures of tin ores from Cornwall and Devon in south-west Britain.

However, the assertion that British tin was a key resource for Mediterranean civilizations is far from universally accepted. The idea of a robust long-distance tin trade between Britain and the Eastern Mediterranean has been a topic of debate for centuries. Many scholars question the scale and frequency of such trade, pointing out significant gaps in the evidence.

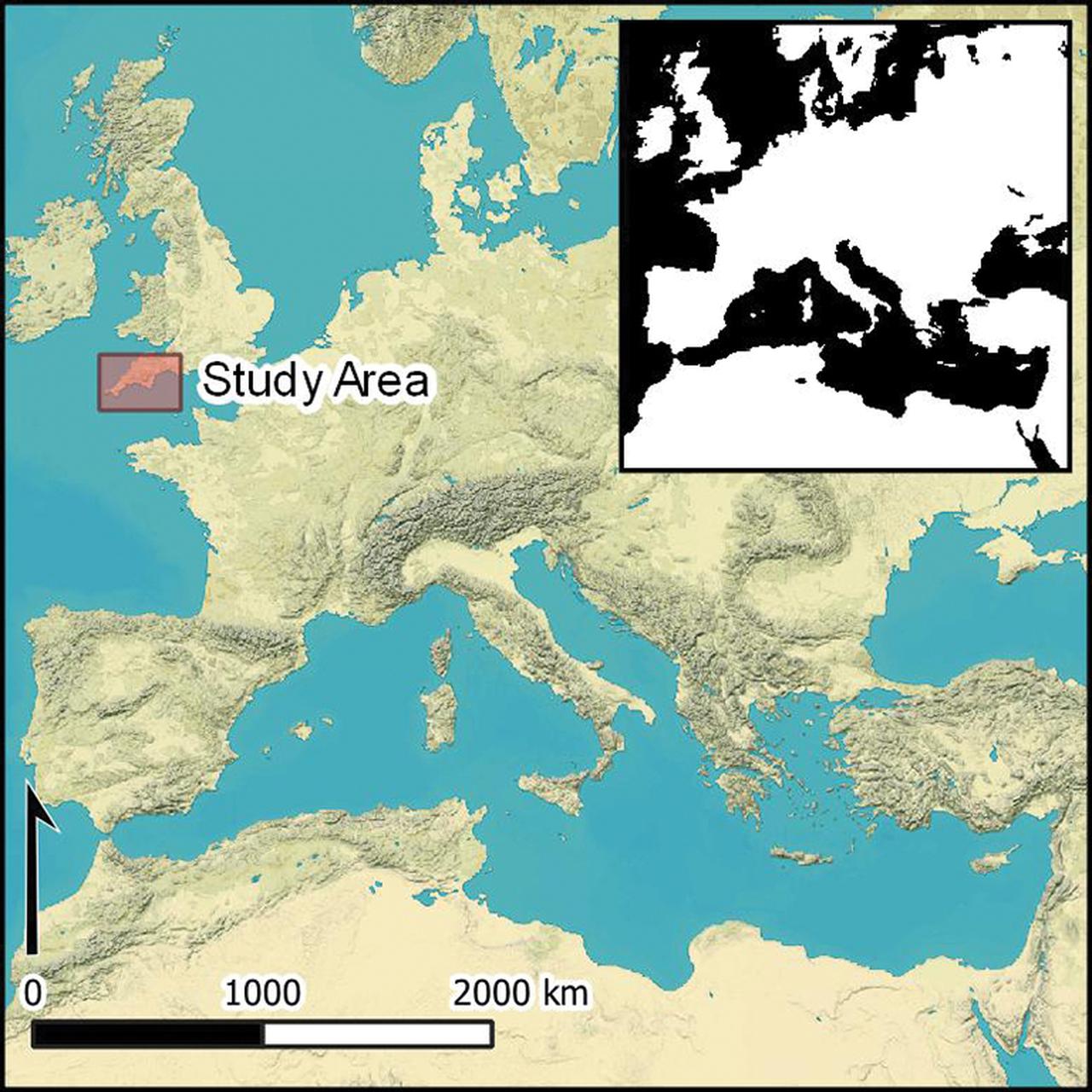

The research team’s analysis focused on three shipwrecks: one near the coast of Israel, another near southern France, and a third off the coast of Devon. Through advanced chemical and isotopic testing, the team linked the tin ingots found in these wrecks to the ore sources in Cornwall and Devon. They argue this proves a direct trade route between Britain and the Mediterranean.

But is this conclusion as strong as it seems? The evidence, while intriguing, may not be as definitive as the study suggests. The identification of British tin in these shipwrecks does not necessarily confirm regular or large-scale trade. Alternative explanations, such as intermediate trading through multiple regions or occasional small-scale exchanges, remain plausible.

The Bronze Age, beginning around 3,300 B.C., was defined by the widespread use of bronze, an alloy of copper and tin. The sources of tin, a relatively rare metal, have always been a point of contention among archaeologists. The earliest known tin mining and production sites date back to around 3,500 B.C. in what is now Türkiye. From here, tin spread across the ancient world, fueling the rise of complex societies.

After all, Cyprus island, near Türkiye, named after copper, one of the most important resources of the period, was also an important resource in the Mediterranean. The most commonly used version of the name Cyprus refers to the overseas copper trade, whereby the island gave its name to the Latin word for copper, aes Cyprium, meaning “Cypriot metal”, which was later shortened to Cuprum.

Ancient texts, such as those by Pytheas of Massalia, who traveled to Britain around 320 B.C., describe tin trading from an island he called Ictis, which some believe is modern-day St Michael's Mount in Cornwall. But these texts were written long after the Bronze Age and may reflect myth or legend rather than historical fact.

Critics argue that the study overstates the importance of British tin in the ancient Mediterranean. They note that while British tin was identified in a few shipwrecks, this does not prove a consistent or dominant role in Mediterranean trade. Tin could have been traded indirectly, moving through multiple regions before reaching the Mediterranean.

Furthermore, tin sources in Central Asia, the Iberian Peninsula, and even North Africa were well-known in antiquity. These regions had well-established trade networks that may have supplied Mediterranean civilizations with the metal they needed for bronze production.

The Durham study offers important data, but it should be viewed as part of an ongoing debate rather than a final answer. The presence of British tin in some Mediterranean shipwrecks is a fascinating discovery, but it is not enough to rewrite our understanding of Bronze Age trade.

In conclusion, after examining one shipwreck near Israel and one each off the coasts of France and Britain, the claim that the Mediterranean was the primary source of the world’s tin remains beyond what archaeology can currently prove with material-based evidence. This interpretation overlooks the shipwrecks discovered along the Levantine coast and the production workshops identified throughout the Mediterranean region. More comprehensive archaeological evidence is required to support such a claim.