The process of Iranians settling in India, which began with Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni’s expeditions to the subcontinent, continued in the following years with increasing momentum. Persian reached its peak during the Mughal era, but with the fall of the Mughal Empire, it was almost abruptly erased from Indian history. The Iranian interest in the region persisted for many years, and they played a role in the spread of Islam there. While Arabic fully aligned with Islam, Persian too projected an image closely associated with Islam during this period. Once the West’s decline in the face of the Muslim world came to an end, it embarked on a course of colonization. Entering the colonial race later than Spain and Portugal, the British nevertheless surpassed both nations, rising to the status of “the empire on which the sun never sets.”

The relationship between Iranian peoples and India dates back to ancient times. Many have observed similarities between Iran’s Zoroastrian faith and the ancient beliefs of the Indians. Moreover, the two peoples share the same linguistic roots, as evidenced by the Indo-Aryan language family. The reason the “Aryan” part is mentioned second is that Sanskrit dates back further in history. Although Sanskrit today has very few speakers, it remains a highly influential language with a rich literary tradition. The strength of a country’s language reflects the strength of its literature.

In the Avesta, the sacred text of Zoroastrianism, the name of India appears repeatedly. There are remarkable similarities between the Indian religion (the Vedas) and the Avesta. Reverence for fire and the sanctity of the cow are common to both. In the Indian sacred texts, the deity Mitra appears, while in the Avesta he is known as Misra. Likewise, the Yima legend in the Rigveda (belonging to the Indians) bears resemblance to the Jamshid legend in the modern era. In both belief systems, “giants” are acknowledged and believed in. During the Sassanian era, there was a famous expedition to India led by Borzūya, the physician who served as chief minister. As a result of this journey, the work Kalīla wa Dimna was translated from Sanskrit into Persian. Indo-Iranian relations thus entered a new phase, marked by significant cultural exchange.

A history of the world could be written solely by examining the evolution and development of languages. In this sense, languages provide us with vast resources. During the Achaemenid era, Old Persian was in use; during the Sassanian era, Middle Persian; and in the post-Islamic period, New Persian. In all three of these periods, India served as a refuge for Indo-Iranians. Whenever Iranians found themselves in difficult circumstances, they would flee to India and enjoy a period of relative comfort there. Lahore is among the important cities of Islam, and Iran’s primary influence has been on the region that today constitutes Pakistan. During the time I studied Urdu, I observed that the language had been enormously influenced by Arabic, Persian, Turkish, and English—but, in my impression, the language that influenced it the most was Persian. Thus, even through the lens of languages alone, a historical narrative can be constructed, offering valuable insights for researchers.

When the Islamic conquests toppled the Sassanids, some Zoroastrians fled to India to avoid converting to Islam. Later, during the reign of Shah Ismail, the region’s Muslims were forced to escape to India due to the oppressive and rigid Shi’ization policies of the time. When the Baha’i faith emerged in the modern era, its followers could not endure the oppression in Iran and fled to India.In both periods, Persian was introduced to the region, and the Persian-Islamic culture became widespread. During the Mongol era, Iranians once again fled to the Indian lands and established themselves there. The states in that region valued the Persian-speaking Iranians, protected them, and entrusted them with important positions within the government.

The Iranians preserved their culture from the Sassanian period. Wherever they went, they Persianized those places. The Turks were influenced by Persian, and the Arabs, in turn, were influenced by Persian as well. In the book Turkish-Iranian Influences, it is stated:

“… The Abbasids began wearing Iranian clothing, modeled their state organization on Iranian institutions such as the vizierate and executioner positions, built their new capital Baghdad near the former Sassanian capital, constructed great palaces like the Achaemenids and Sassanians, and supported scholars and artists who praised their administration. The Abbasid Caliphate was at the height of Persian influence even at its lowest point.”

As this excerpt shows, Iranian culture could revive at times, influence other cultures, and Persianize the peoples of the region. We will see a similar phenomenon in the Indian subcontinent.

During the period when Islam illuminated the region, Arabic came to the forefront, while Persian remained dormant for about 200 years. This led nationalists like Zarrinkub to refer to this era as the "200 years of silence." However, during the Tahirid and Samanid periods, Persian began to revive. In the Samanid era, a figure like Rudaki—often regarded as the father of New Persian—emerged and produced literary works. In the same period, Firdausi’s efforts to revive Persian and his dedication of his work to Sultan Mahmud are also noteworthy. With Sultan Mahmud’s reign, expeditions to India reached their peak, with many campaigns launched to various regions. Thousands of Persian-speaking Iranian soldiers took part in these expeditions and settled in the region.

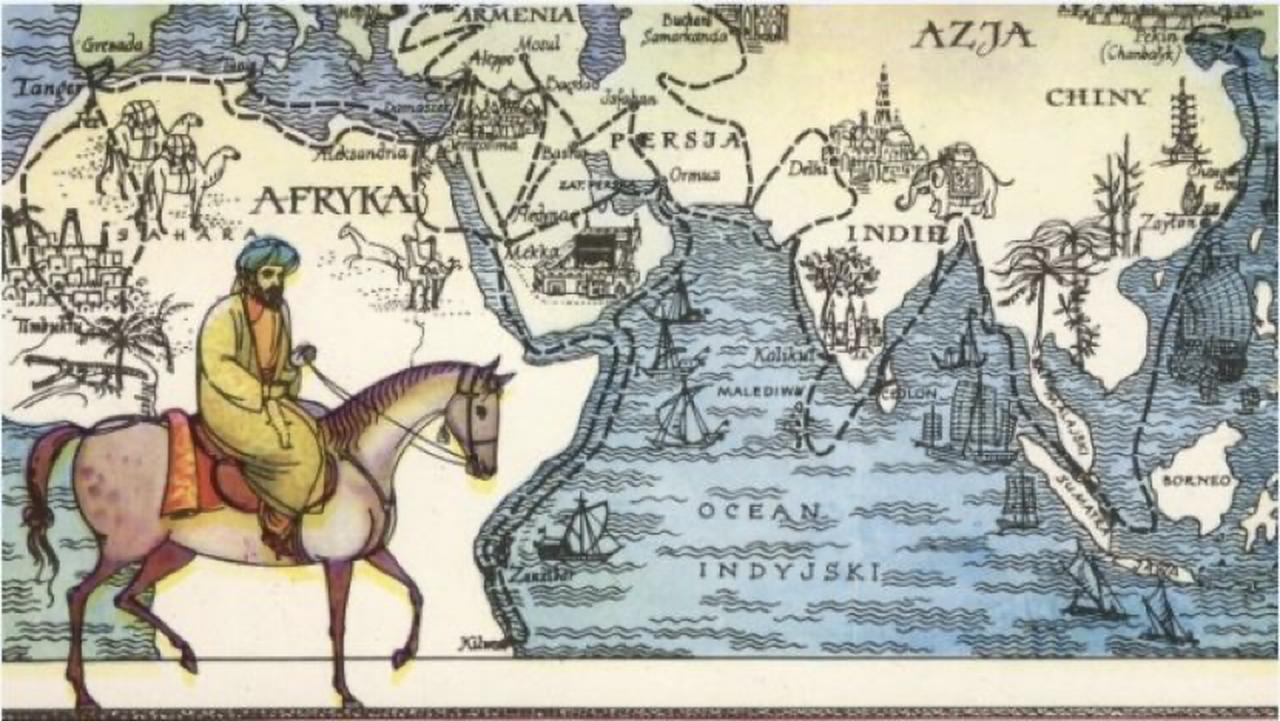

An important traveler I want to highlight here is Ibn Battuta. He stayed in India for nine years and held positions such as judge (qadi) during his time there. Although he faced death threats several times, he generally maintained good relations with the ruler of the period. Ibn Battuta did not know Persian, and the ruler at the time did not know Arabic.

In his writings, Ibn Battuta mentions many Persian words that were in use during that era. He communicated with people through an interpreter and, despite belonging to a different sect, was entrusted with the position of qadi. He witnessed great generosity in the region and recounts striking events. Iranian scholars note that Ibn Battuta referred to the Persian Gulf as the “Fars Gulf” and study the Persian language of that period. His travelogue contains numerous Persian words such as heftchuš, dervaze, nemidānem, šunīdem (šenīdem), and Berūv! (boro!). Examining his book from this perspective would be very valuable.

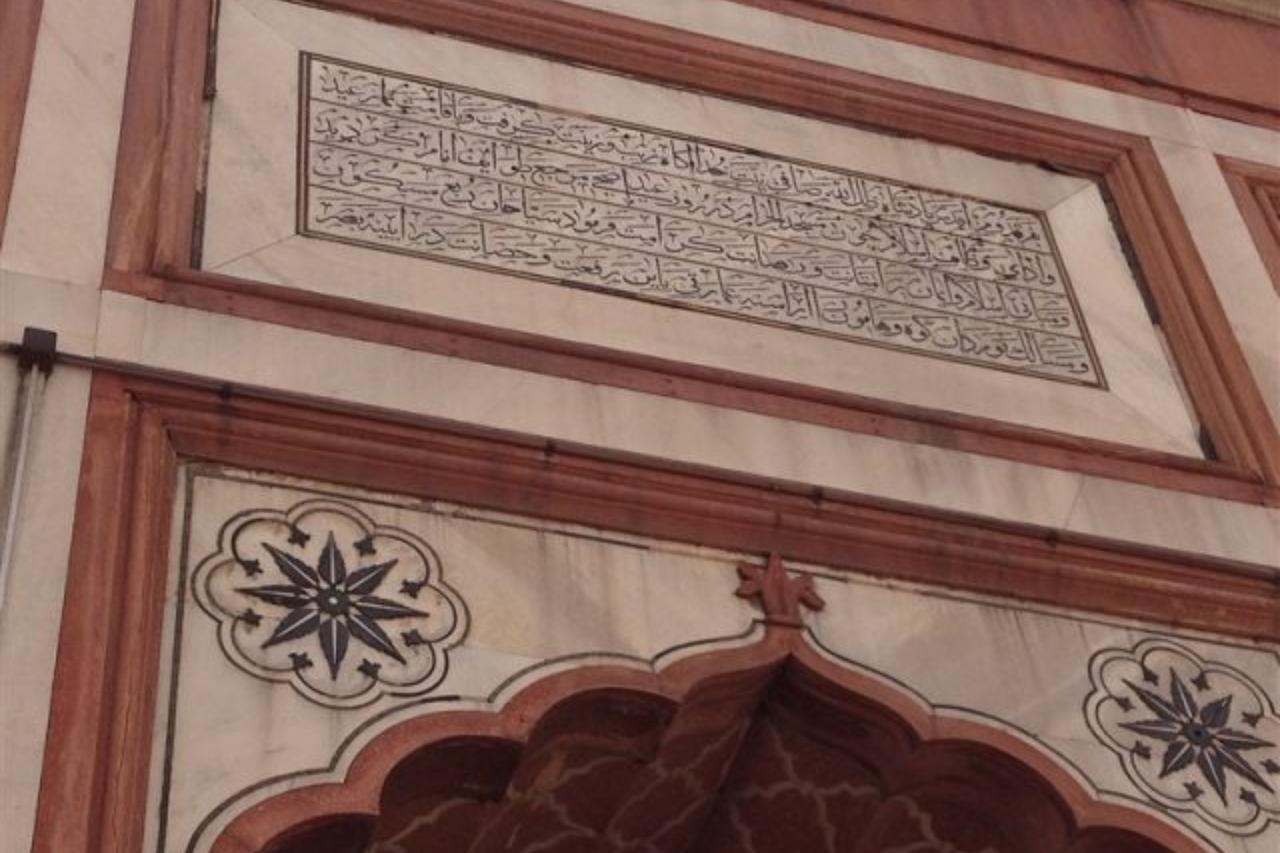

A significant part of Iranian culture is also indebted to the Turks who ruled over the Indian subcontinent. Among the dynasties that governed the region for nearly 800 years, whether of Iranian origin or not, all upheld the Persian language and often gave it special status. Persian reached its zenith during the Mughal period and remained the dominant language in the region for many years until the British introduced English. The very first book on Sufism was written here, along with dozens of Persian grammars and dictionaries. The first female poet to write in Persian, Rabia Khuzdari, lived in this region. Sufism flourished here and has continued to the present day. Verses of the Qur’an were rendered in Persian poetic form, which eased the acceptance of Islam among the Indians. Rulers such as Firuz Shah Bahmani, Yusuf Adil Shah, Sultan Jalaluddin Firuz Shah Halci, and Zahireddin Babur were among those who composed Persian poetry.

During the Safavid era, some 700 poets migrated to India, helping to spread Persian throughout the region. Persian became so widespread during the Mughal period that some rulers wrote their memoirs in Persian and even critiqued Persian poetry. Under Emperor Akbar’s reign, the Dar al-Tarjama (House of Translation) was established to translate Sanskrit works into Persian. Indian religious texts were among the first translated, as there was a desire to understand Indian beliefs and to exert influence in the region. Efforts were made to comprehend both the similarities and differences between Islam and Indian religions, and these translation activities continued for several generations.

Iranians came to the region for trade, to spread Sufism, and to obtain government positions. As Persian became the language of the Diwan—that is, the bureaucracy—Indians began learning Persian as well. For centuries thereafter, knowledge of Persian facilitated access to privileges. Ibn Battuta recounts the story of Sharif Abu Gurra, who, after being accused of misgoverning, set out under the pretext of visiting a tomb and fled to India. Many individuals from Iran and neighboring areas regarded India as a refuge.

Persian has a journey of 600 to 800 years in India. This journey came to an end and lost its former influence after the turbulent years of the Mughal era, when it had reached its peak. By the 19th century, the Mughals—weakened by Nadir Shah—were forced to leave the region to the British. Iranian influence can be seen in the monuments built by the Mughals. When Nadir Shah took control of the region, he also took the Mughals’ wealth to his own country and did not collect taxes from his own people for three years. Aware of India’s wealth, the British arrived in the region from the 1600s onward and finally seized control in 1857-58, putting an end to Persian dominance shortly after.

Persian quickly lost its former strength and appeal. Today, India has 22 official languages and hundreds of dialects and languages. Persian, however, was recognized in 2020 as one of the nine classical languages taught in Indian schools. Persian is the historical language of India’s “medieval period,” and among nearly 10 million manuscripts, one million are written in Persian. There are many institutions in India dedicated to preserving these Persian manuscripts.

In this regard, I consider it important to conduct more specific research and to better understand neighboring Iran. Naturally, during their ventures in India, the Turks did not abandon their native Turkish language, but Turkish remained primarily the language of the dynasty. Nevertheless, Persian and Arabic served as the languages of science, scholarship, and social life for centuries. I also believe that Turkish did not receive the attention it deserved in the face of this cultural dominance. If we are to take lessons from history, I think this issue deserves reflection as well. Therefore, it is appropriate to carry out further research on this topic. It is clear that there is a need for in-depth studies, especially those that can offer insights relevant to the present day, which will hold particular importance.