History has a way of whispering its secrets, if you listen closely…

Light flickered across the empty corridors of the Yildiz Palace as soldiers of the Macedonian Action Army pried open safes, cabinets and velvet-lined jewellery boxes. Diamond tiaras, emerald necklaces and strings of pearls were placed into wooden crates alongside priceless earrings, bracelets, brooches, rings, jewel-encrusted boxes and gold clocks. When no one was watching, pieces quietly vanished, slipped into the pockets of officers, pushed down the boots of sergeants, and tucked beneath the tunics of privates. And in this way, the Star Palace that once shimmered with imperial courtly splendor stood stripped, its silence heavier than the plundered treasure itself.

The ransacking of the Yildiz Palace was not the consequence of a natural disaster or the opportunism of an angry mob. It was the calculated spoils of victory after the deposition of Sultan Abdulhamid II in April 1909. For over three decades, Abdulhamid ruled the Ottoman Empire from behind the high walls of his fortress-like palace overlooking the Bosphorus. The palace was the heart of his power, and the symbol the Young Turks sought to dismantle.

Following the counter-revolution of the March 31 Incident, the Army of the Committee of Union and Progress marched into Istanbul to restore order and force the sultan’s removal. Abdulhamid was deposed on April 27 and sent into exile in Salonica with his family, leaving behind his home, its treasures abandoned to fate.

What followed was a spree of sanctioned plunder. Soldiers, emboldened by new authority and a long-standing resentment toward the old regime, stormed through the palace with a revolutionary zeal that veered into vengeance. Carpets were rolled up and carried away. Clocks, china, silverware, gifts from foreign sovereigns and intimate possessions of the harem were tossed into piles. Photographs show soldiers posing on furniture, relaxing on the lawns, even clambering over the ornate marble fountain in crude triumph.

Every palace has experienced transition … but few have been stripped with such malicious intent and disrespect.

Among the seized items was an extraordinary collection of pieces that had passed from sultan to sultan: diamonds once belonging to Sultan Mahmud II, pearls worn by the daughters and consorts of Sultan Abdulmecid and Sultan Abdulaziz, emeralds inherited by Sultan Murad V, and the jewels Sultan Abdulhamid II had amassed during his reign.

These were part of the Hazine-i hassa, the private treasury of the sultan. According to custom and tradition, they should have passed to Sultan Mehmed V Resad. Instead, the Young Turk leadership declared them State property. The Committee of Union and Progress framed the confiscation as a moral act, reclaiming wealth allegedly hoarded by an autocrat, and as a necessary step to ensure the survival of the nation. The empire was in debt, its army in need of reform, and its navy almost obsolete. Selling the jewels, they argued, would fill the Treasury and help modernize the military.

Thus, pieces once worn by imperial princesses and consorts were cataloged, packed, and shipped away—not to the Imperial Treasury at Topkapi, not to Sultan Resad at Dolmabahce, but to an auction house in Paris.

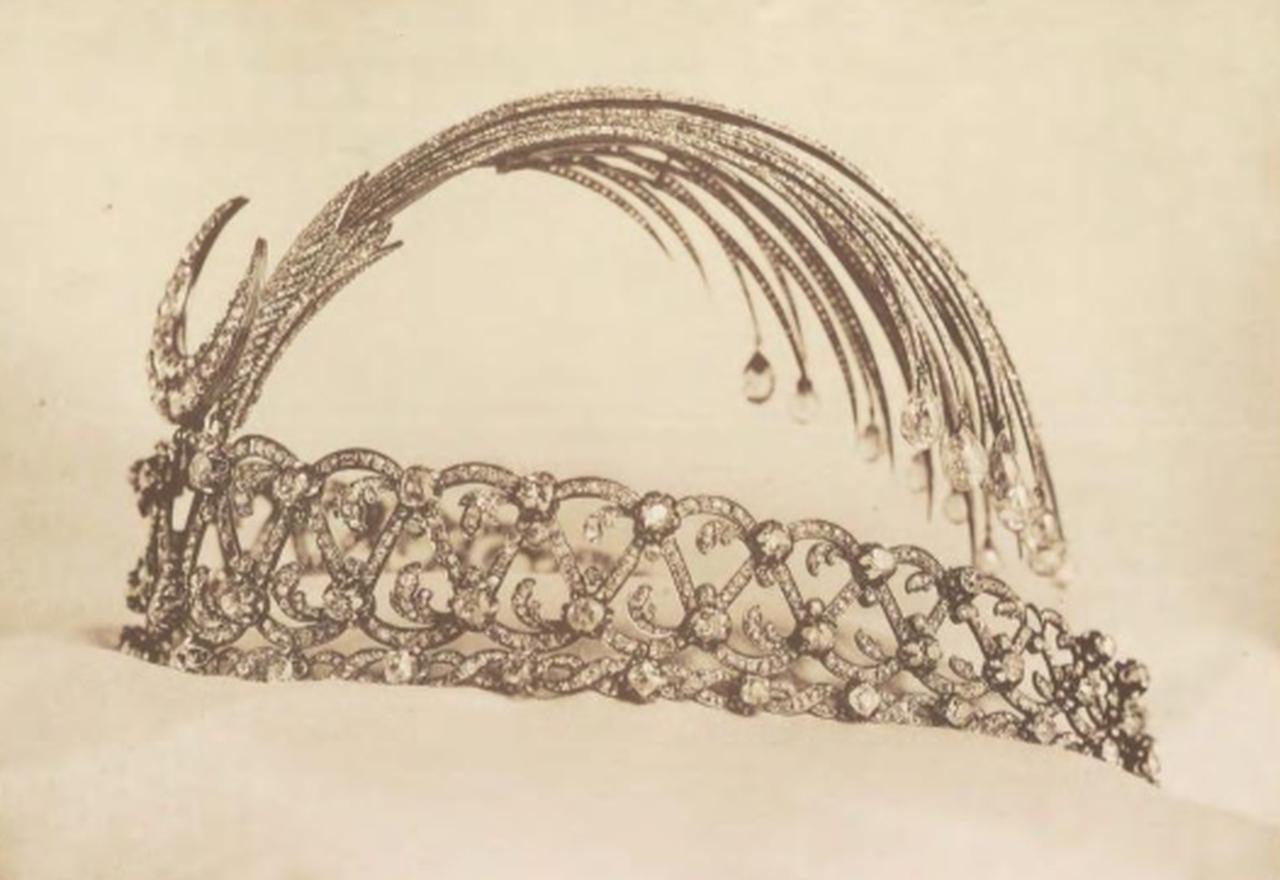

In November 1911, the treasures of the Ottoman Sultanate arrived in Paris, an event that electrified the French capital. At the Galerie Georges Petit and the Hotel Drouot, aristocrats, collectors, jewellers, reporters and curious onlookers crowded into the salons, drawn by the prospect of seeing the jewels of the Ottoman Court. Glass vitrines glittered under the electric light, each one displaying wonders that seemed almost too spectacular to be real: diamond tiaras crowned with the Ottoman crescent moon; riviere necklaces made of stones as clear as ice; pearl corsage brooches shaped like stars and flowers; bracelets and earrings set with rubies the colour of pomegranate seeds.

The international press covered the event with fascination. Never before had the private collection of a reigning dynasty been sold so publicly. It was unprecedented. It was scandalous. It was sensational.

Some pieces were bought by European nobility, others sailed across the Atlantic to be worn by American heiresses. Many were purchased by jewellers who promptly dismantled them—exquisite examples of Ottoman craftsmanship broken apart for their stones, lost forever.

The revenue from the sale proved far below the Young Turks’ expectations. Yet the true cost is immeasurable: the dispersal and erasure of Ottoman cultural heritage.

Today, as visitors walk through the restored buildings of the Yildiz Palace, recently reopened after a remarkable program of renovation, they enter rooms that were once stripped bare by looting soldiers. The palace has regained its splendor, but when you visit the former home of Sultan Abdulhamid II, consider what is no longer there. The jewels that once glittered beneath these high ceilings are gone—scattered across continents, locked in foreign vaults, remounted in modern settings, or long since lost. How extraordinary it would have been to see them return, to restore the sparkle of the Imperial Ottoman Court.

As you wander through the gardens, linger a moment before the marble fountain where soldiers of the Action Army once posed for photographs. Stand in the corridors, close your eyes, and imagine wooden crates being hauled away, heavy with plunder. Picture diamonds, rubies, emeralds and sapphires slipping into a soldier’s pocket, vanishing forever.

And ask yourself, what does it mean for a nation when its treasures, its symbols of continuity, legitimacy, and tradition, are scattered to the winds?

Sometimes, history does not just whisper its secrets. Sometimes, it mourns them.

Until we meet again in the next “Sultan’s Salon”…