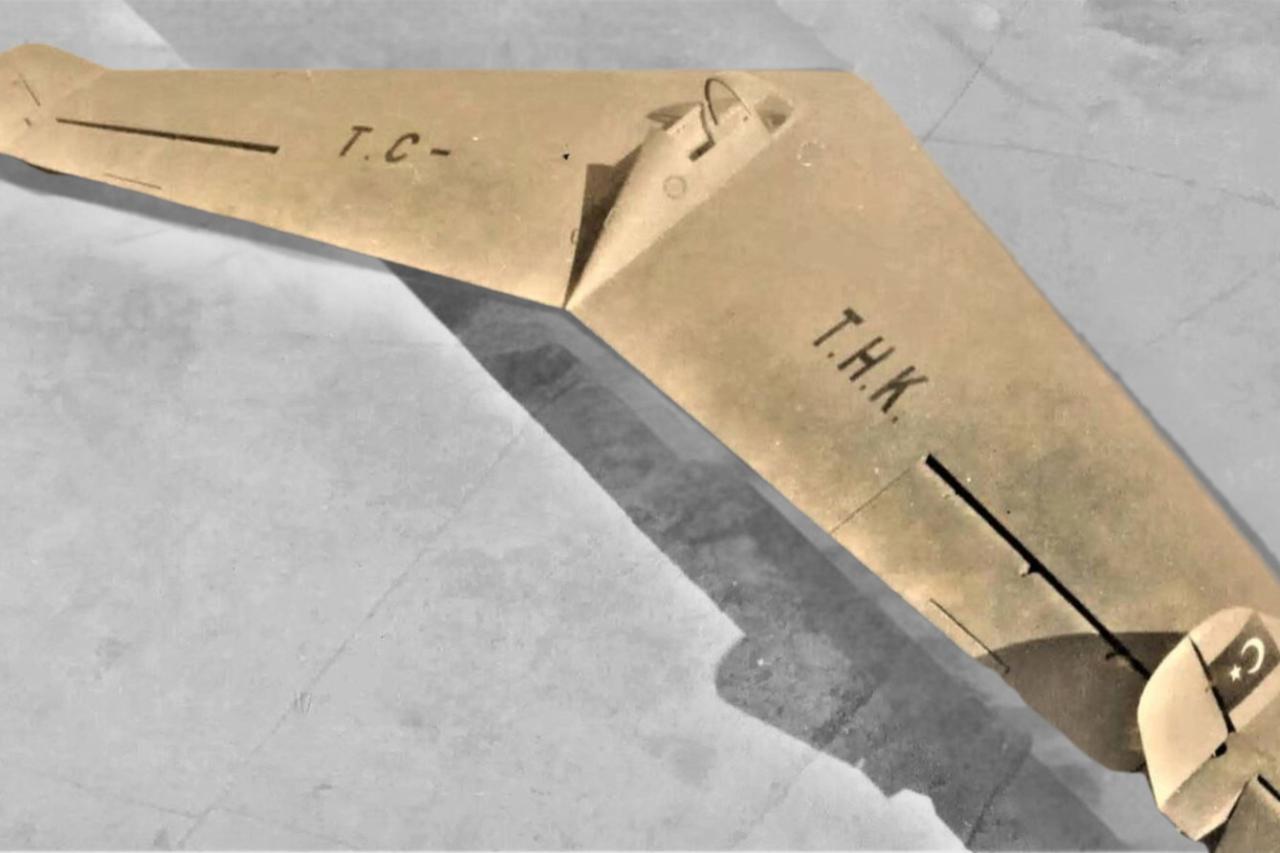

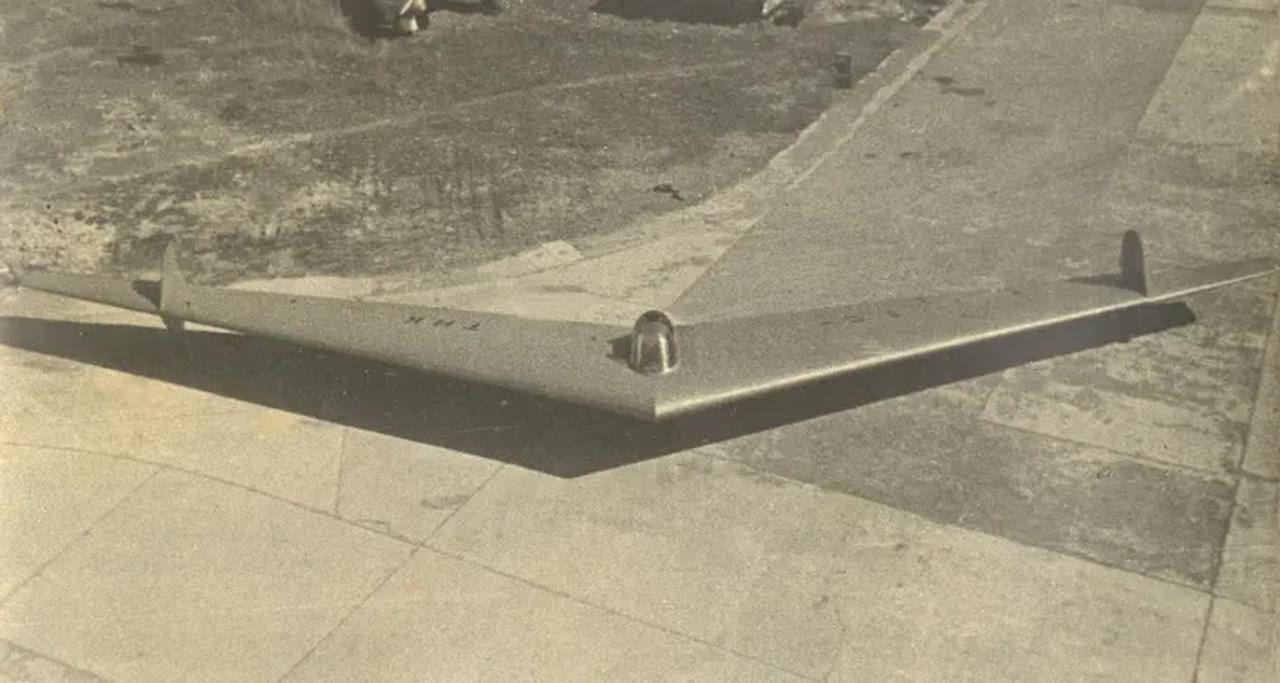

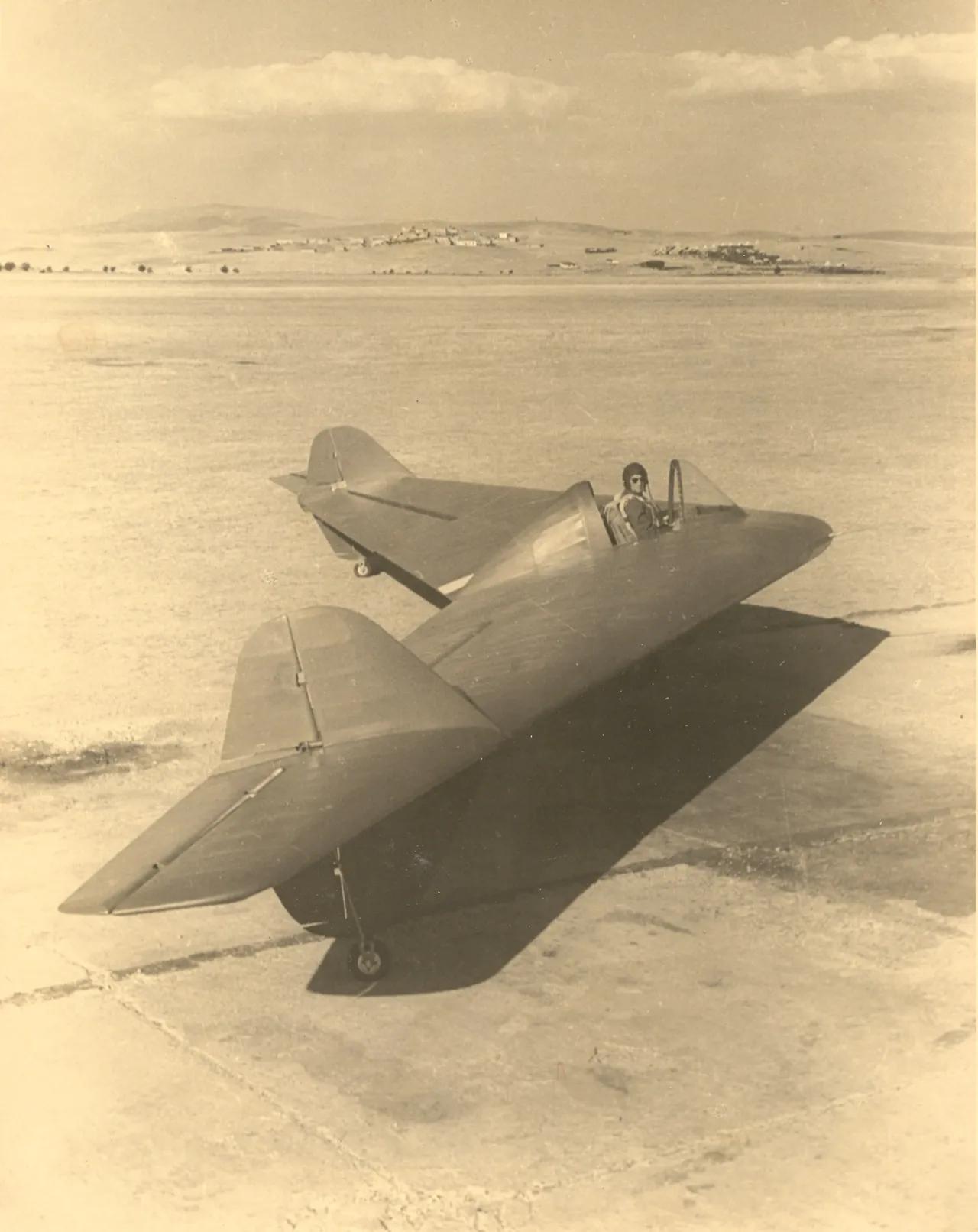

In the summer of 1948, a remarkable test flight took place over the skies of Ankara. The THK-13, like the American B-2, a futuristic, radar-evading glider developed by the Turkish Aeronautical Association (Turk Hava Kurumu, or THK), briefly soared above the capital. Designed at the Etimesgut Aircraft Factory, the project reflected a vision far ahead of its time, seeking to bring Türkiye into the vanguard of post-war aeronautical innovation.

Developed as THK’s 13th original aircraft design since its founding in 1925, the project symbolized Türkiye’s rising engineering capabilities. It was led by chief design engineer Yavuz Kansu, with a dedicated team including Saffet Muftuoglu, Necati Alper, Orhan Olmez, Omer Ciftci, and Emel Dilmen. Pilots Kadri Kavukcu and Cemal Uygun carried out the test flights. At the time, the head of THK was Seyfi Duzgoren, who viewed the aircraft as a lifeline for Türkiye’s dwindling domestic aviation industry.

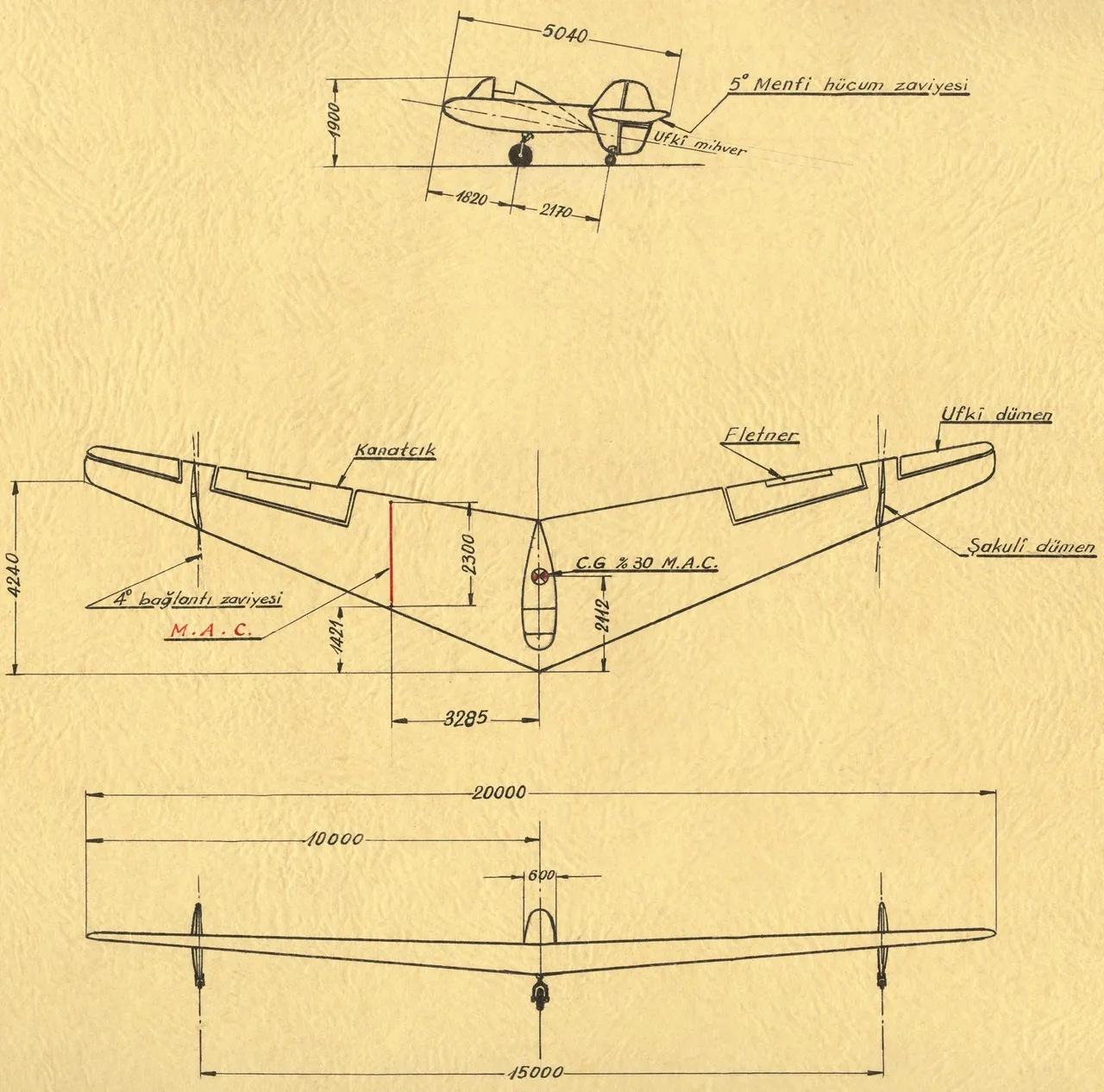

While training in the United States, Yavuz Kansu had been captivated by the "flying wing" concept—an aircraft without a distinct fuselage or tail, designed for stealth and aerodynamic efficiency. On his return to Türkiye, Kansu presented a proposal to THK leadership, which was approved on Jan. 31, 1948, by the factory's director Selahattin Beler. The resulting glider, named THK-13, was envisioned as a stepping stone toward producing radar-evading aircraft.

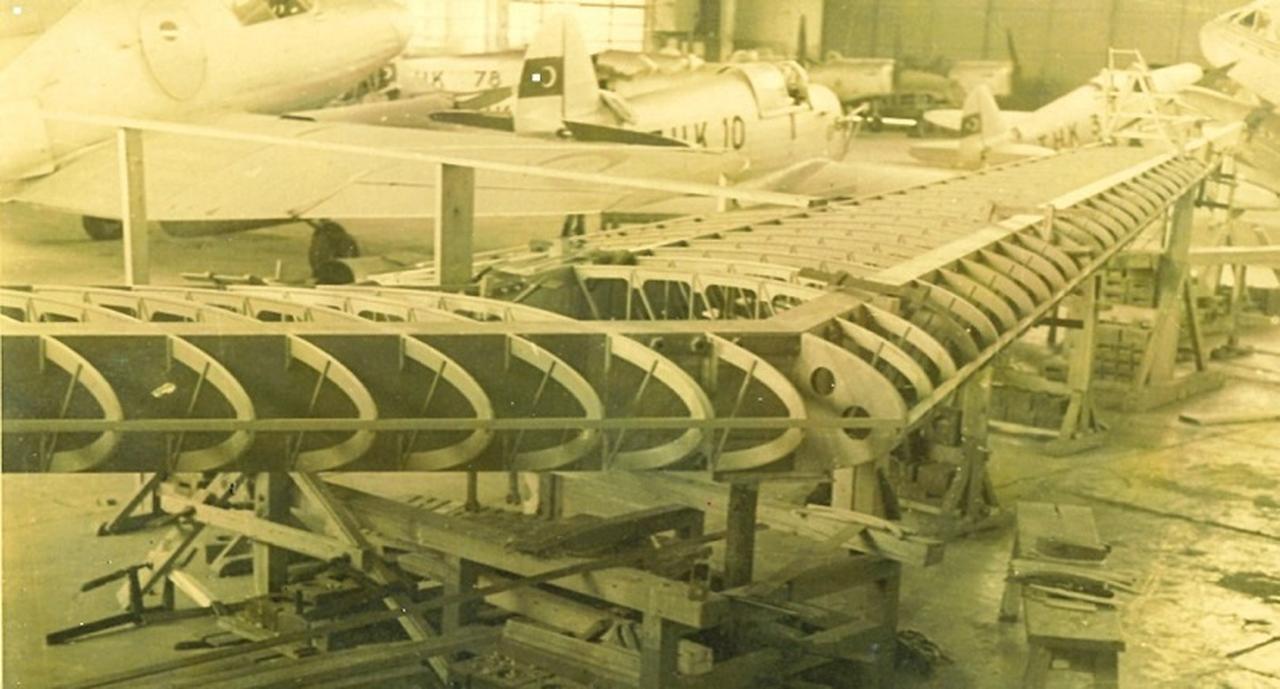

The design process was influenced in part by the German Horten brothers, pioneers in flying wing concepts. Although wind tunnel testing in France was considered, budget constraints led the engineers to improvise. They mounted a one-tenth scale model of the flying wing onto an existing THK-5 aircraft for airborne testing—an experimental approach believed to be the first of its kind worldwide.

By July 1948, construction of the prototype was complete. Taxi and bounce tests began soon after. However, development was rushed, and unresolved technical issues, especially a persistent pull to the right during flight, were not fully corrected.

On Aug. 26, 1948, the THK-13 took to the skies for the first time, towed by a tug plane over the Cankaya district of Ankara. The flight was intended to impress political leaders and gain support for continuing aircraft production at THK. However, soon after release from the tow, the glider veered off and landed hard on a hillside near Cankaya, sustaining minor damage. It was repaired and flown again, this time over the Turkish Military Academy, where a rough landing caused more serious damage and injuries to the pilot.

Although THK publicly announced that the glider would be repaired and flown again within 20 days, most press coverage was harsh. Newspapers accused the factory of abandoning aircraft production and instead taking furniture orders—a narrative that deeply undermined the project’s credibility.

On Sept. 29, 1948, a second test flight was scheduled. Pilot Cemal Uygun carried out preliminary ground tests and confirmed the glider was ready. Though designer Yavuz Kansu suggested further jump tests using a tow plane, Uygun insisted everything was in order. THK President Seyfi Duzgoren, who was scheduled to depart for Mardin, requested that the flight take place that same day.

Despite unresolved control issues, the THK-13 was launched at 6 p.m. Once airborne, it again veered right and crashed violently, injuring the pilot and causing significant damage to the aircraft.

A post-crash investigation revealed a clamp had been accidentally left inside the right wing, which jammed the control system. Uygun later reported this oversight as the main cause of the accident. However, Kansu and other engineers believed pilot inexperience and hasty flight decisions played a major role.

Though the original glider was beyond repair, the team began work on a second THK-13 prototype, completing it in August 1949 after 15,000 hours of labor. But test flights never resumed. By then, political winds had shifted. The United States' Marshall Plan aid, received in 1947, encouraged Türkiye to rely more heavily on imported aircraft. Following the recommendations of the Thronborg Report in 1948, Türkiye began phasing out its aircraft manufacturing programs.

THK President Seyfi Duzgoren fiercely opposed this shift, viewing the flying wing project as a final chance to keep domestic production alive. He wrote repeatedly to government ministries, warning of the long-term consequences. Not long after, he passed away, under circumstances many believed were influenced by both the intense pressure of the period and the media backlash.

While the THK-13 met a tragic end, it was not alone. The same year, the United States suffered its own flying wing disaster: the crash of the Northrop YB-49 on June 5, 1948, which killed test pilots Daniel Forbes and Glen Edwards.

Both later had major U.S. airbases named after them. The YB-49 was shelved until the 1990s, when the flying wing concept re-emerged as the B-2 stealth bomber.

More than seven decades after the THK-13 was grounded, Türkiye is once again flying the wing—this time with no pilot on board. In a striking technological evolution, the ANKA III unmanned combat aerial vehicle (UCAV), developed by Turkish Aerospace, draws upon the same aerodynamic vision that once inspired the THK-13.

First taking to the skies in December 2023, ANKA III represents Türkiye’s most advanced step in low-observable aerial warfare. Like its predecessor, it features a flying wing configuration—an aircraft design without a distinct fuselage or tail, optimized for stealth. But unlike the THK-13, this platform is jet-powered, fully autonomous, and built for combat.