The Turkish hammam has long stood as more than a place of bathing—it has served as a spiritual and communal institution central to Muslim society.

Researchers emphasize that, unlike the Graeco-Roman thermae, which mainly functioned as centers of leisure, hammams evolved within Islamic culture as spaces where physical cleansing and religious practice intertwined.

Professor Mesut Idriz of the University of Sharjah highlights that the hammam was directly tied to Islamic rituals requiring full-body purification.

The practice of ghusl, the major ablution carried out after specific conditions such as childbirth, menstruation, or sexual intercourse, found a natural home in the hammam.

By providing access to clean water, hammams made it possible for ordinary believers to fulfill religious obligations linked to purity.

Idriz also draws attention to the broader spiritual symbolism of water in Islam, noting that Quranic references to water as the source of life elevated the hammam’s role far beyond hygiene.

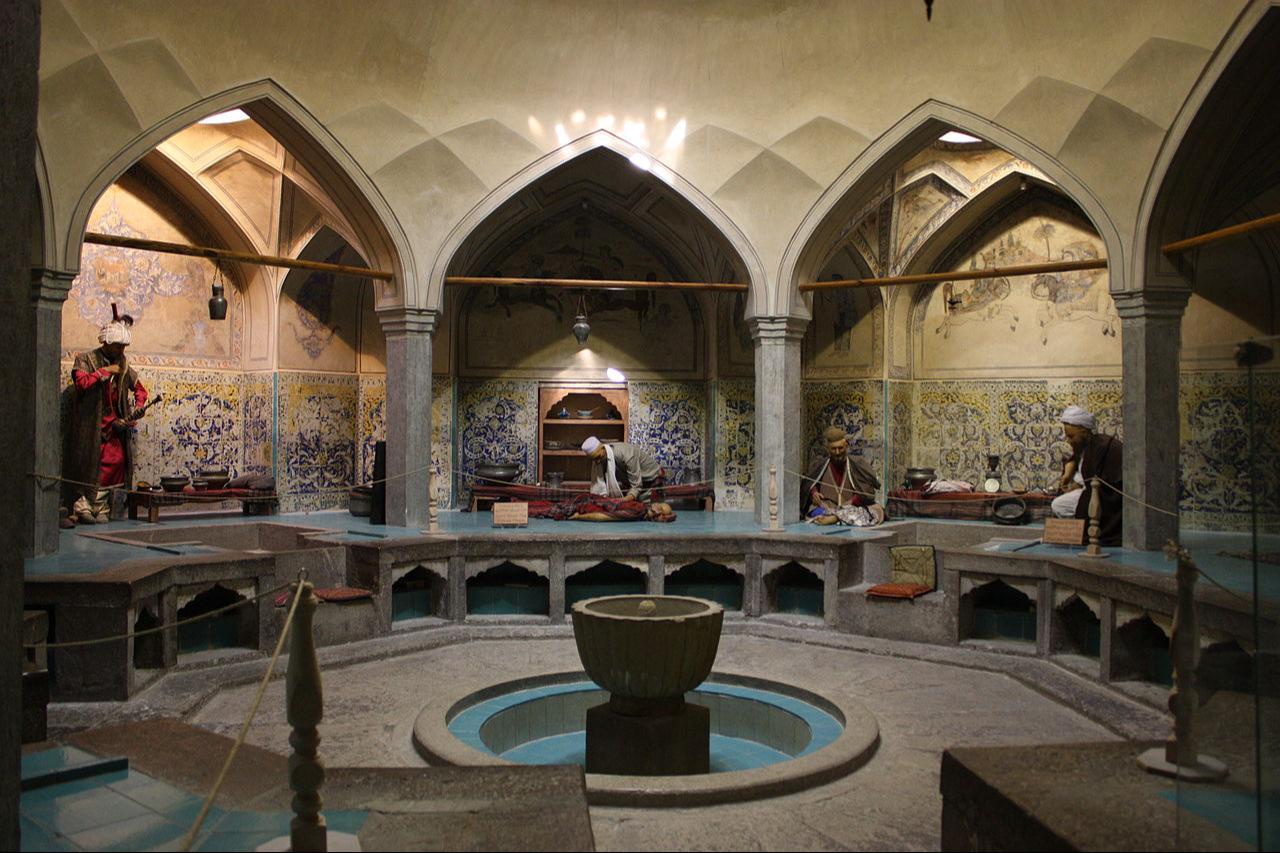

From the early Islamic period, hammams became integral to urban planning. Constructed alongside mosques, caravanserais (lodgings for travelers), and madrasas (Islamic schools), they shaped the religious and social fabric of Ottoman cities. In many cases, as Eyup Kul of Recep Tayyip Erdogan University explains, founding a hammam was considered as vital as opening a school.

Ottoman hammams were also linked to waqfs—religious endowments that funded urban infrastructure and social services.

Entrance fees were kept low so that people of all backgrounds could access them, while officials inspected the baths regularly to ensure cleanliness and order.

Professor Ebru Ibish of the International Balkan University stresses that Islam places equal weight on hygiene and spirituality.

She connects the hammam to the well-known saying, “Cleanliness is half of faith,” which positioned the bathhouse as a cornerstone of religious and social life.

She underlines that visiting a hammam was not merely about washing the body but also about aligning with the constant reminder in Islam that inner and outer purity are inseparable.

Though not originally an Islamic invention, hammams spread from the Middle East and North Africa to the Balkans and Andalusia, adapting to local traditions while retaining gender separation and Islamic practices.

During the height of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century, Istanbul counted around 230 hammams, though only about 60 remain active today.

Many historic hammams now serve new roles as galleries or cultural venues, such as the Daut Pasha Hammam in Skopje, which houses the National Gallery of North Macedonia.

Scholars argue that reviving hammam heritage offers not only historical insights but also opportunities for wellness tourism, heritage conservation, and urban development.

Professor Idriz believes that exploring hammam traditions across regions can shed light on how Islamic principles of cleanliness, spirituality, and social equality were adapted to diverse cultures.

In his view, hammams historically embodied the idea of a “clean body and a clean society,” promoting health, hospitality and moral conduct.