Türkiye’s National Intelligence Organization (MIT) has made public a rare historical intelligence document concerning Thomas Edward Lawrence, widely known in the West as “Lawrence of Arabia,” shedding light on how British intelligence activities were perceived and monitored in the late Ottoman and early Republican periods.

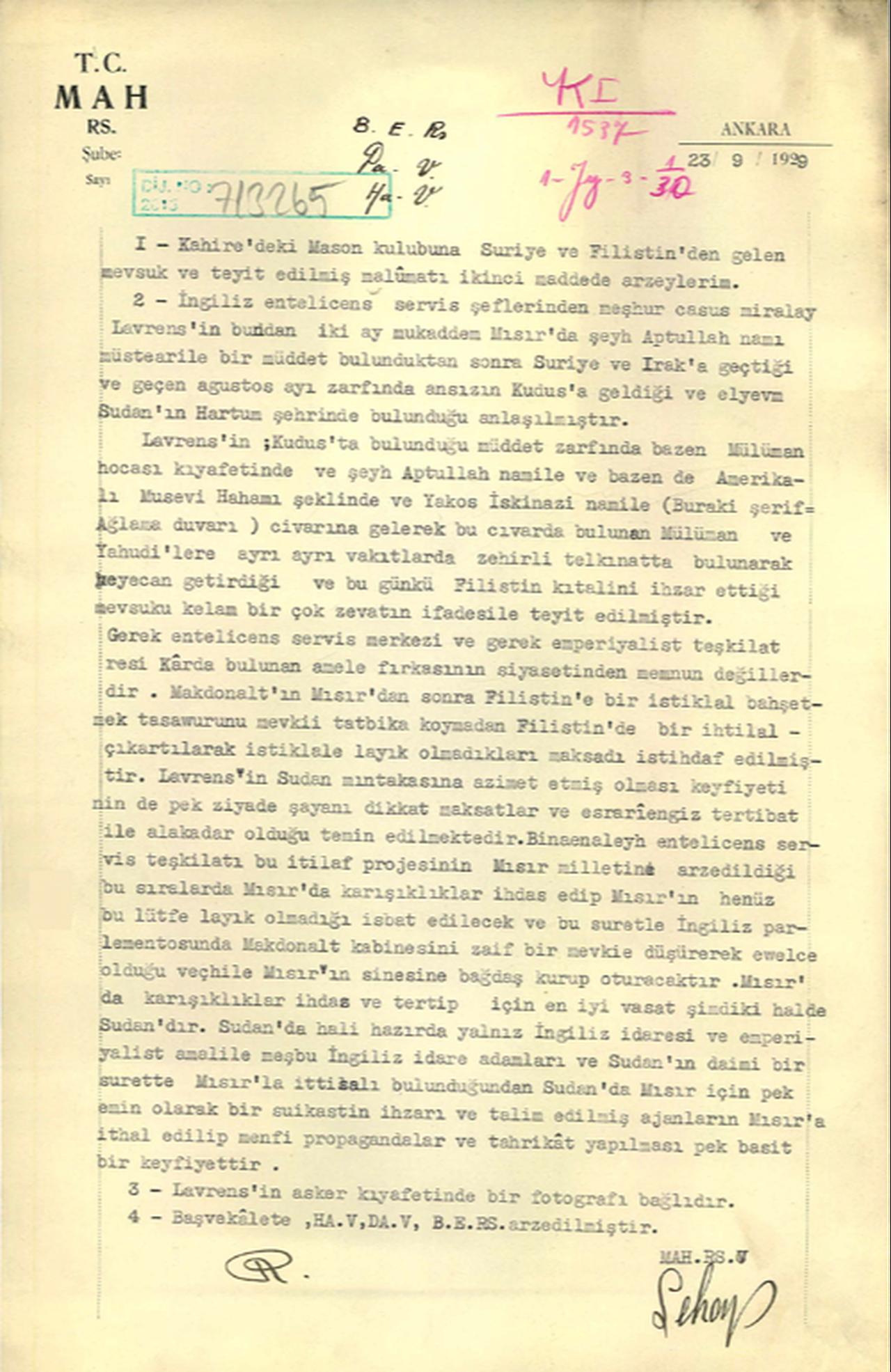

The document, dated September 23, 1929, has been added to MIT’s official website under the “Private Collection” section within the “Documents” archive.

It was originally prepared by the Directorate of the National Security Service and circulated to key state institutions, including the General Staff and the Ministries of Interior and Foreign Affairs.

According to the report, Lawrence, described as a prominent British intelligence officer, was said to have moved across Egypt, Syria, Iraq, and Palestine while using different disguises and assumed identities.

The document claims that he stayed in Egypt under the alias “Sheikh Aptullah,” later traveled through Syria and Iraq, appeared unexpectedly in Jerusalem, and was ultimately located in Khartoum, Sudan.

The report includes an account that Lawrence allegedly alternated between disguises, at times posing as a Muslim religious teacher and at other times as an American Jewish rabbi under the name “Yakos Iskinazi.”

While in Jerusalem, he was accused of engaging separately with Muslim and Jewish communities, delivering what the document described as provocative messages aimed at stirring tensions around the area of the Western Wall, known in Islamic tradition as al-Buraq.

A photograph of Lawrence in military uniform was attached to the intelligence note, reinforcing the seriousness with which Ottoman-era security authorities viewed his movements and activities.

Beyond personal movements, the document reflects broader geopolitical concerns of the period. It suggests that British intelligence circles were dissatisfied with labor movements and political dynamics in Egypt and Palestine at the time.

Indirectly quoting the report, it states that unrest was allegedly being encouraged to undermine arguments for independence, particularly in Palestine, and to weaken the political position of British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald in Parliament.

Sudan was identified in the document as a strategically suitable base for organizing unrest, given its administrative links to Egypt and the presence of British officials aligned with imperial interests. The report implies that trained agents and negative propaganda could be funneled into Egypt from Sudan with relative ease.

Experts also draw attention to the broader historical context in which archaeology, military planning, and intelligence work became increasingly intertwined.

Biblical archaeology, which focused on locations mentioned in the Old and New Testaments, initially centered on regions now within Türkiye, Syria, Egypt, Iraq, Iran, Jordan, Israel, and Palestine.

From the eighteenth century onward, excavations in these areas were largely conducted by American, British, and French teams.

Lawrence himself worked alongside figures such as D.G. Hogarth at the Oxford museum and C. Leonard Woolley, the archaeologist who uncovered the ancient city of Ur. Their fieldwork extended to sites including Carchemish, Jerablus, Damascus, Aqaba, Petra and Sinai.

During these excavations, large numbers of artifacts were removed from their original locations and transferred to Western museums. As the Ottoman Empire weakened, European powers increasingly relied on archaeological surveys and mapping projects to support territorial ambitions.

Following World War I, the unstable political environment in the Middle East brought archaeologists into closer cooperation with military and intelligence institutions.

During the war, Lawrence led activities linked to the Palestine Exploration Fund, which conducted excavations in southern Palestine and Syrian territories.

Additionally, excavations carried out by the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute at Megiddo between 1925 and 1939 received backing from the Rockefeller family, highlighting the role of private Western funding in major archaeological projects.