As the world marks the 100th anniversary of the first examination of Tutankhamun’s mummified remains in November 1925, archival evidence shows that what is often remembered as a defining moment in archaeology was also a moment of profound destruction. Howard Carter’s team used hot knives and physical force to remove the young pharaoh from his coffin, leading to his decapitation, the severing of his limbs, and the dismemberment of his torso—followed by an attempt to conceal these actions.

This reassessment appears in an analysis by Eleanor Dobson for The Conversation, who revisits the excavation’s disturbing details through surviving records and photographs.

Tutankhamun’s tomb, discovered in the Valley of the Kings in 1922 by Carter and a team composed mostly of Egyptian excavators, took years to clear and catalogue.

Delays caused by disputes between Carter and the Egyptian government slowed progress, and the pharaoh’s remains were not reached until 1925. This moment triggered a renewed surge of public fascination known as “Tutmania,” which had already begun after the tomb’s discovery made headlines around the world.

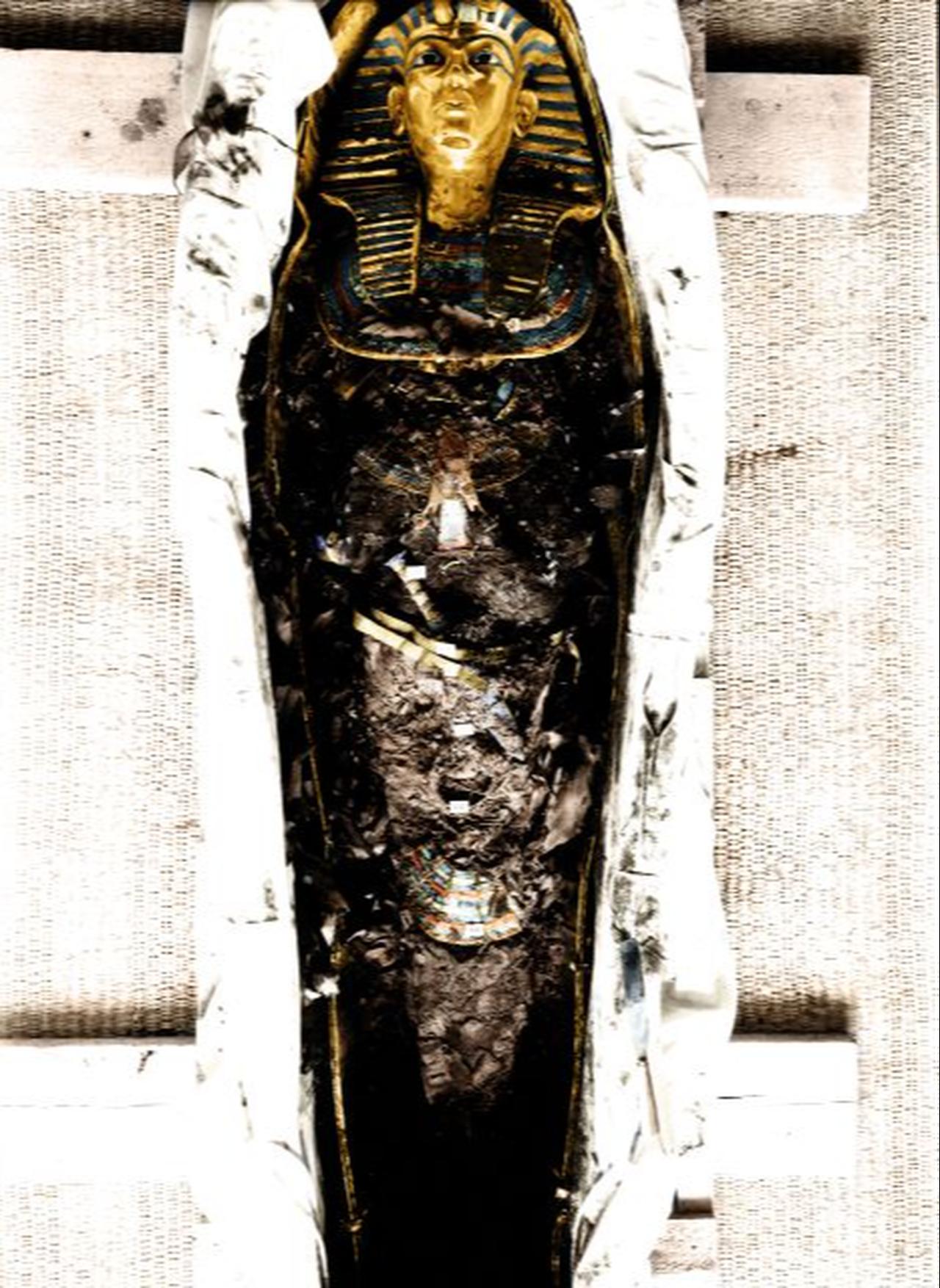

When the innermost coffin was opened, Carter’s team found the body fused to the casket by a hardened, black, pitch-like resin used in ancient burials to protect the deceased from decay.

Carter described the corpse as “firmly stuck” and wrote that “no amount of legitimate force” could release it. After attempts to soften the resin by placing the coffin under the sun failed, the team cut through the wrappings and body with heated knives, severing the head and funerary mask in the process.

The autopsy left Tutankhamun, in Carter’s own words, “decapitated, his arms separated at the shoulders, elbows and hands, his legs at the hips, knees and ankles, and his torso cut from the pelvis at the iliac crest.”

His body was later glued back together to create the appearance of an intact mummy, masking the extent of the damage.

Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley has noted that Carter did not mention the destruction in his public account or in his private notes held today at the University of Oxford’s Griffith Institute. She proposes that his silence may have been intentional, either to cover up the violent methods or to preserve, at least publicly, the dignity of the ancient king.

Yet the omissions were exposed in photographs taken by archaeological photographer Harry Burton, which show, among other scenes, Tutankhamun’s skull impaled to keep it upright for documentation.

Burton’s stark photographs contrast sharply with the image Carter selected for the second volume of The Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen in 1927.

In that publication, the pharaoh’s head was shown carefully wrapped to hide the severed spinal column, offering readers a sanitized narrative that obscured what had taken place inside the tomb.

One hundred years later, the excavation is increasingly viewed not only as a milestone in Egyptology but also as a reminder of the ethical complexities behind some of archaeology’s most celebrated moments. The mutilation of Tutankhamun’s remains—hidden in official accounts and revealed only through archival material—continues to challenge long-held narratives of heroic discovery.

Carter wrote in his diary on November 11, 1925, that “Today has been a great day in the history of archaeology,” yet the surviving evidence points to a far more troubling reality beneath the surface of the celebrated find.