As the Ottoman Empire reeled from the 1877-1878 war with Russia, countless tragedies unfolded across the Balkans and the Caucasus.

Among the silent victims of this brutal conflict was a four-year-old girl named Ayse, whose life was forever changed after being taken by Russian forces. Recast in a foreign land as “Maria Konstantinovna Kexholmskaya,” her story is a chilling reminder of the war’s devastating human toll, one rarely acknowledged in military histories.

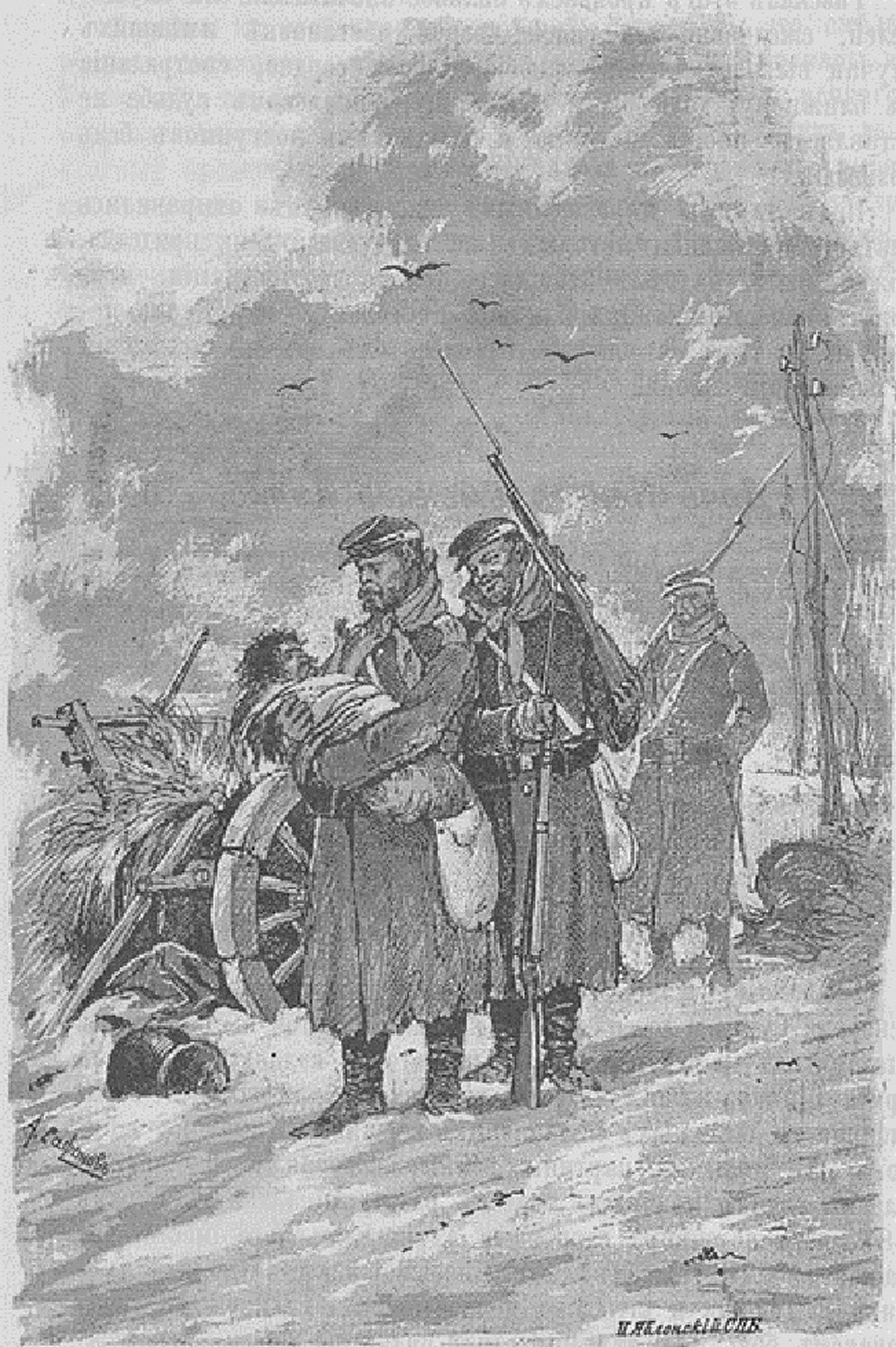

The war, known in Türkiye as the "93 War," left deep scars on the region. In the village of Kuruchesme near Ruse (present-day Bulgaria), Ayse was found next to her dying mother, freezing in the bitter Balkan winter. She was discovered by Mikhail Dmitrievich Saenko, a soldier of the elite Kexholm Guard Regiment. Wrapped in a Russian greatcoat, she was taken in by the unit as they marched toward Istanbul.

Though she could speak no Russian and knew only her name, Ayse quickly became a mascot for the regiment. Soldiers made her a tiny uniform, built a camp cradle for her, and eventually voted unanimously to adopt her as the “daughter of the regiment.”

In May 1879, Ayse was baptized into the Orthodox faith. Her name became Maria Konstantinovna Kexholmskaya — a patronymic tribute to her godfather, Lieutenant Konovalov — and her surname, Kexholmskaya, linked her forever to the military unit that adopted her.

With the support of high-ranking officers, including General Panyutin and even the Russian imperial family, Maria was enrolled in the Warsaw Marinsky Institute for Noble Maidens. Her academic achievements were closely monitored by her military guardians, who regularly visited her, bringing sweets and flowers.

Despite her success in adapting to Russian life, many accounts describe her as distant and somber—a girl who never truly smiled and rarely looked others in the eye.

After graduating in 1890, Maria married Alexander Iosifovich Shlemmer, an officer from a wealthy Volyn family of German descent. The wedding was held in Warsaw, with gifts from the Kexholm Regiment and even a jeweled bracelet from the Tsar. But her fairy-tale integration into imperial society masked the trauma of exile and cultural loss.

The soldier who first found her, Sayenko, was invited to the wedding, though he did not attend. She settled in Lutsk and lived a quiet life until World War I broke out.

During World War I, Maria left the safety of Moscow and worked as a nurse in the 3rd Guards Infantry Division’s field hospital. Revered by wounded soldiers, she became known as a selfless caregiver, earning the affectionate nickname "Masa."

But the Russian Revolution forced her southward, and while working in Sochi, she contracted tuberculosis.

She died in 1920 in Yalta, far from the land of her birth, and just months before her husband was executed by the Bolsheviks in Sevastopol.

Her eldest son, Pavel, died during the Russian Civil War, and her younger son, Georgi, the last surviving member of the family, died in West Germany in 1974.

Although the original trauma of her displacement was never truly addressed, Maria’s life has been preserved in Russian memory through romanticized literature, art, and media. In 2001, the local government of Priozersk—formerly Kexholm—established the Maria Kexholmskaya Award for outstanding female students, further enshrining her as a model figure of imperial loyalty and success.

Yet from a Turkish perspective, her story is far more painful. Ayse was not merely rescued—she was taken. Her identity, religion, language, and homeland were stripped from her, replaced with the expectations of an occupying empire.

Unlike many Ottoman Muslim children during the 93 War who perished or vanished without a record, Ayse survived—but only by becoming someone else.