The question of who inherits the political, cultural, and intellectual legacy of the ancient Greek, Roman, Eastern Roman, and Ottoman worlds continues to shape historical debates well beyond academia. Among today’s nation-states, Italy, Greece, and Türkiye stand out as central stakeholders in this long and complex continuum.

While Italy is commonly associated with ancient Rome and Greece with Ancient Greek and Classical Hellenism, a growing body of scholarship places Türkiye at the core of the Eastern Roman, often called Byzantine and Ottoman inheritance, based on geography, continuity, and institutional succession.

For readers, it is essential to clarify that the term “Byzantine Empire” is not a name used by the people who lived within that state. The population of the Eastern Roman Empire referred to themselves as "Rhomaioi," meaning "Romans," and viewed their polity as the continuation of the Roman Empire.

The label “Byzantine” emerged much later, during scholarly studies in early modern Europe, and was formalized as an academic term in the nineteenth century. It is therefore a historiographical convention rather than a historical self-definition.

This distinction matters because it reshapes how imperial continuity is evaluated. When Turkish sources argue that the Eastern Roman legacy survives in Türkiye, they do not base this claim on ethnic origin or language alone. Instead, they point to the transfer and preservation of political authority, the uninterrupted control of core imperial territories, and the continuation of social, administrative, and institutional practices that linked the Eastern Roman state to its Ottoman and modern successors.

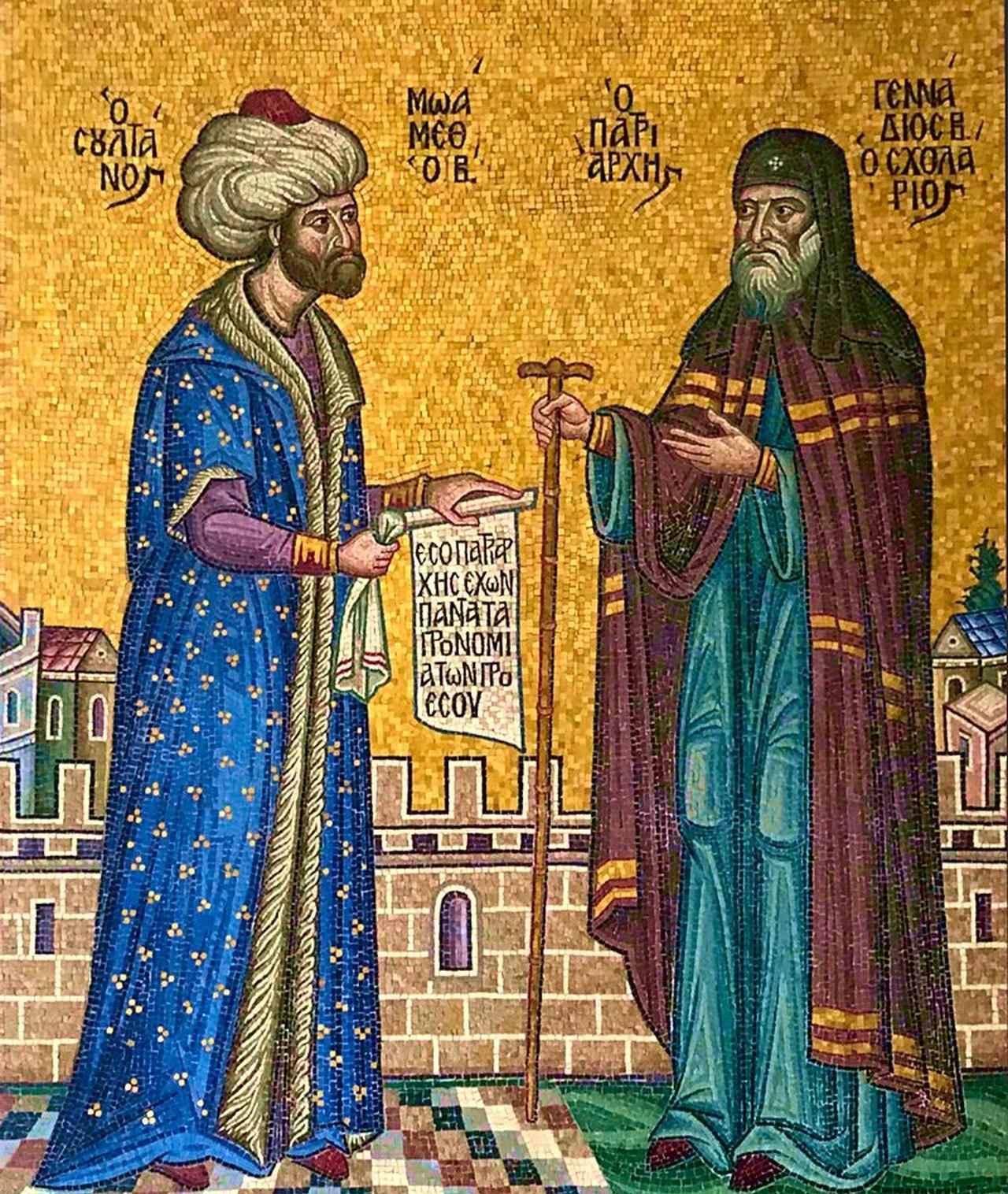

The core argument positioning Türkiye as the primary heir of the Eastern Roman state rests on continuity of place and governance. The former Eastern Roman capital, Constantinople, now Istanbul, remains the political and cultural heart of Türkiye. The state that succeeded the Eastern Roman Empire, the Ottoman Empire, did not abandon the Roman institutional framework but absorbed and adapted its administrative, military, and legal traditions.

The Ottoman polity functioned as a continuation rather than a rupture. The Ottoman use of the term Rum, meaning Roman, to describe both land and people underscores this perception. Like the word “Ottoman,” Rum denoted imperial affiliation rather than ethnicity. This perspective frames the modern Turkish Republic not as an external successor, but as the latest phase in a long imperial lineage rooted in Anatolia.

While modern Greece identifies strongly with ancient Greek language and Orthodox Christianity, Turkish scholarship emphasizes that these cultural elements alone do not establish political succession. The modern Greek state emerged in the nineteenth century after nearly 400 years of Ottoman rule. From this standpoint, Greece is described as a state that developed from within the Ottoman imperial structure rather than as a direct continuation of the Eastern Roman Empire.

Accordingly, Greece is presented not as the sole or primary heir of Byzantium, but as one of many partial inheritors of the Ottoman legacy, alongside other successor states. Its connection to Eastern Rome is viewed as cultural rather than institutional, and therefore limited when measured against criteria such as capital, territory, and state tradition.

Central to this debate is the role of Anatolia. Far from being an empty land when Turkic groups arrived in the medieval period, Anatolia was densely populated by diverse communities who largely identified as Romans. The number of incoming Turkic groups is widely considered to have been far smaller than the existing population. Over time, military dominance gave way to coexistence, intermarriage, and cultural exchange.

Rather than remaining a separate ruling elite, the Turks became part of Anatolia’s social fabric. They influenced and were influenced in return, resulting in a gradual process of Anatolianization. This process, according to the source perspective, formed the basis of the modern Turkish nation, which incorporates the human and cultural legacy of earlier Roman populations.

This inclusive understanding of continuity extends to language and cultural production. Works written in Ancient Greek or Latin in Anatolia are not viewed as foreign to the land. Just as texts written in different languages during later periods are embraced regardless of the author’s ethnic origin, ancient literary and scientific works are treated as part of Anatolia’s historical legacy.

Within this framework, the inhabitants of Anatolia today are considered legitimate inheritors of the poets, philosophers, and scholars who once lived and wrote there. Cultural ownership is therefore tied to place and continuity rather than ethnicity alone.

This approach is reflected in modern heritage practices. While Ottoman presence in many former Ottoman territories in Europe is often overlooked or its architectural remains are given limited attention, Anatolia adopts a different model. In present-day Türkiye, remains from prehistoric periods through Ancient Greek, Hellenistic, Roman and Late Antique eras are evaluated as part of the country’s cultural heritage.

These civilizations are not ranked hierarchically; instead, they are treated as equally valuable layers of Anatolia’s past. Archaeological excavations continue across the country, supported by more than five hundred ongoing archaeological digs and surface surveys.

Within this comparative framework, Italy occupies a distinct position. Italy’s claim is primarily linked to Ancient Rome as the birthplace of the Roman Republic and Empire. Unlike the Eastern Roman tradition, which continued for centuries after the fall of Rome in the west, Italy did not maintain institutional Roman state continuity into the medieval period.

As a result, Italy’s connection to Roman heritage is understood mainly in cultural and historical terms rather than through uninterrupted governance. In this narrative, Italy represents the origin of Roman civilization, while Eastern Rome, centered in Anatolia, carried Roman statehood forward.

Viewed together, this framework moves the discussion beyond rigid national ownership and toward a more historically grounded understanding of imperial legacy. Italy, Greece, and Türkiye appear not as rivals competing for the same inheritance, but as participants in different stages of a long and evolving civilizational chain.

Italy is tied to the emergence of Roman statehood, Greece to the survival of ancient language and religious tradition, and Türkiye to the uninterrupted continuation of Eastern Roman space, population, and governance through the Ottoman era.