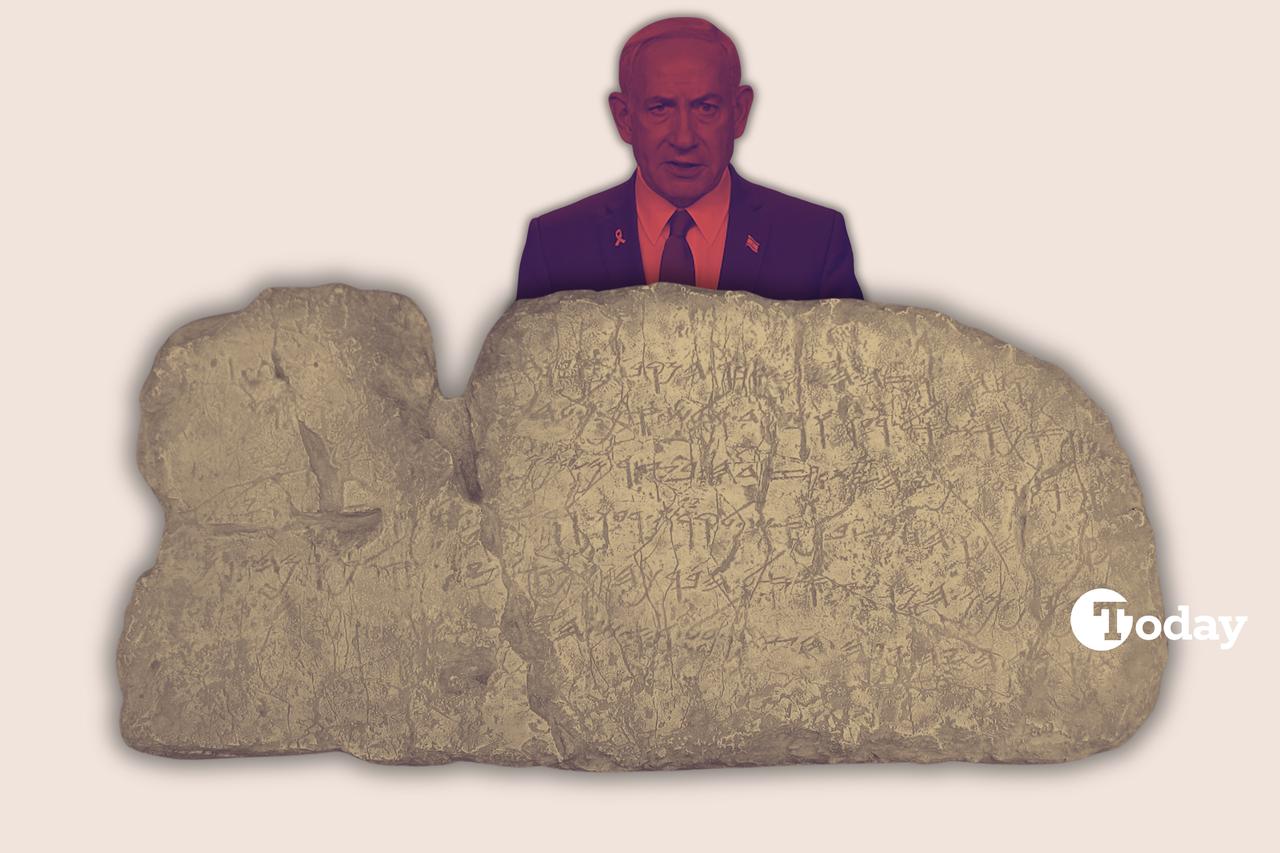

Türkiye’s Istanbul Archaeological Museums hold the 2,700-year-old Siloam Inscription, a six-line Paleo-Hebrew text that resurfaced in politics after Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu recalled seeking it from Ankara in 1998 and being rebuffed.

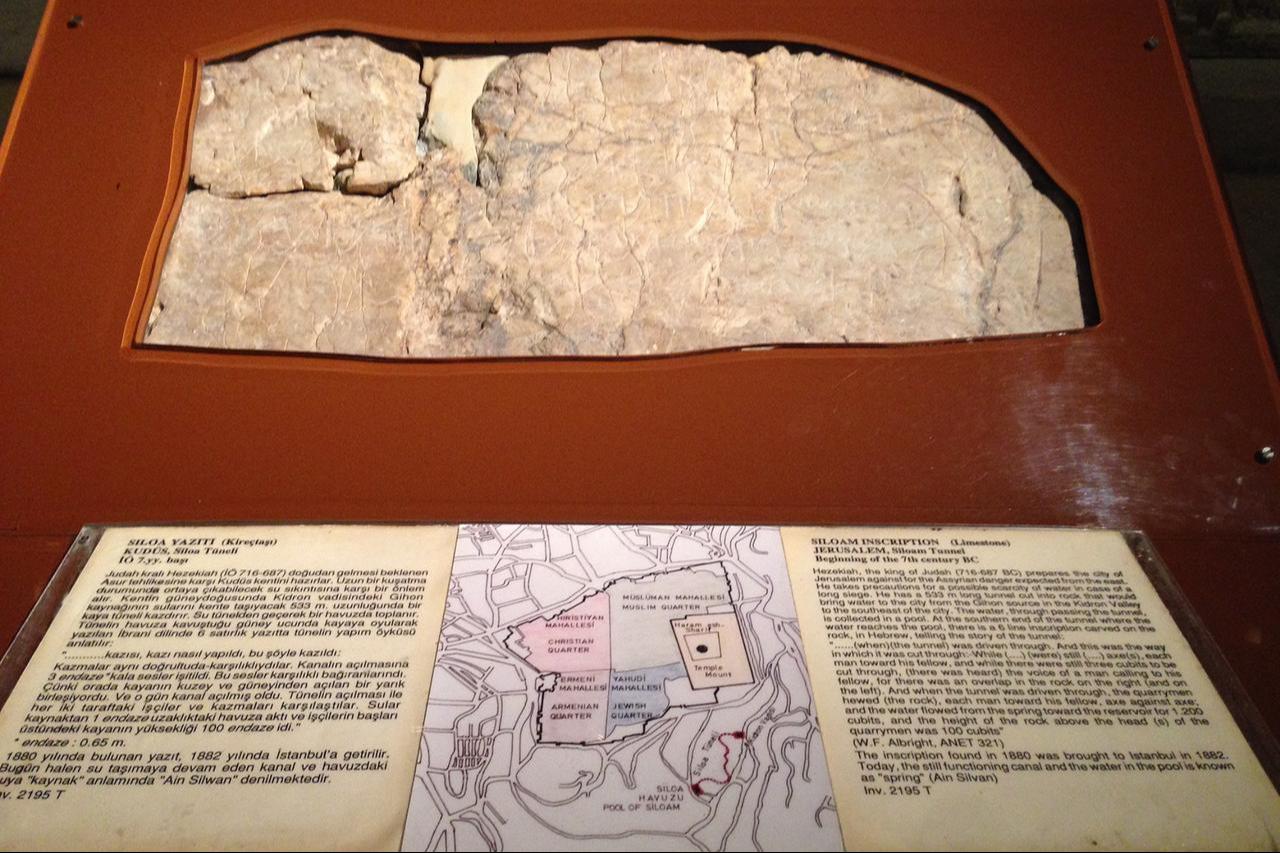

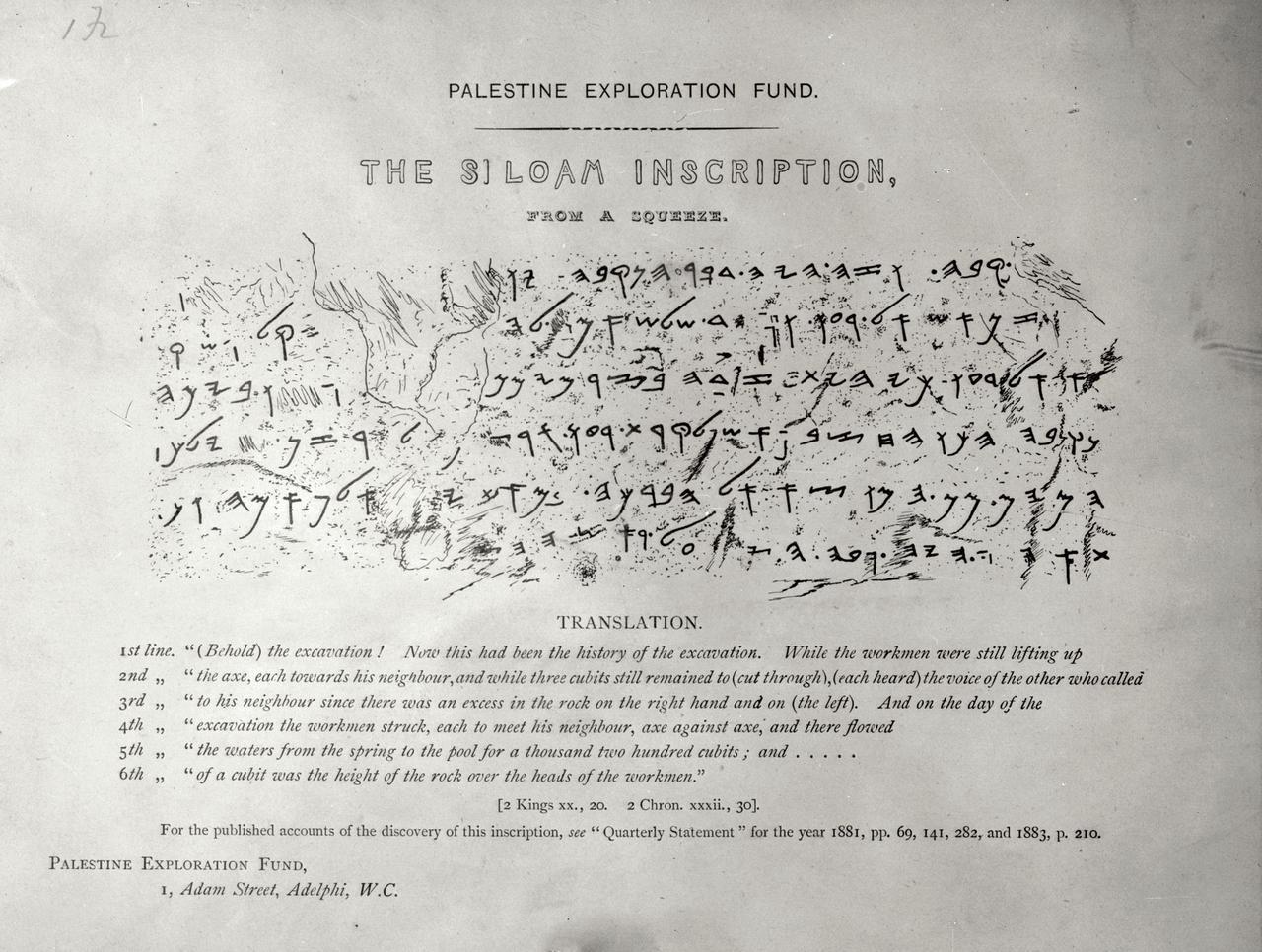

The Siloam (Silvan/Shiloah) Inscription is widely viewed as evidence of early Jewish presence in Jerusalem. It records the completion of a water tunnel project during the reign of King Hezekiah, describing how two teams dug toward each other and met in the middle.

Scholars identify its script as a regional variant of the Phoenician alphabet, often termed Paleo-Hebrew, making it one of the earliest sustained pieces of Hebrew writing.

Discovered in 1880 in the Hezekiah Tunnel near the Siloam Pool in Jerusalem, the stone was brought to Istanbul during the Ottoman period and added to the imperial collection that later formed the Istanbul Archaeological Museums.

Museum officials say the gallery that houses the inscription has been closed for restoration, so the artifact is currently kept in storage; a replica is on view in Jerusalem.

Netanyahu said that in 1998, he asked then-Prime Minister Mesut Yilmaz to transfer the inscription and offered Ottoman artifacts from Israeli collections in exchange.

He recounted being told that the political base of the then-Istanbul mayor, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, would react negatively. In remarks delivered in Jerusalem this month, Netanyahu added, “This is our city … it will never be divided again.”

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan replied, “We will not allow the holy Jerusalem to be defiled by unchaste hands,” reiterating Türkiye’s stance on East Jerusalem.

Over the years, Israeli officials have repeatedly sought the inscription from Türkiye, including requests linked to commemorations and high-level visits.

Reports in 2022 suggesting Ankara might consider a swap were denied by Turkish diplomatic sources, and subsequent approaches to the cultural authorities were again turned down.

The text narrates the engineering feat rather than a religious rite. It speaks of “voices calling” from each side as the crews drew close, notes the meeting of “pick against pick,” and states that water flowed to the pool once the passage opened.

The account aligns with the tunnel’s purpose: to secure Jerusalem’s water supply from the Gihon Spring to the Siloam Pool amid regional threats.

For Israeli leaders, the inscription underpins narratives about ancient roots in Jerusalem. For Türkiye, it remains part of the Ottoman-era collection held in a national museum. As both sides restate their positions, the tablet’s status underscores how archaeology, museum patrimony, and present-day diplomacy continue to overlap.