As sea temperatures continue to rise due to climate change, dangerous marine bacteria known as Vibrio are spreading rapidly from northern Europe to southern coastlines—including those of Türkiye. Once mostly confined to the Baltic Sea, these pathogens have now been detected as far as the North Sea and in semi-enclosed swimming areas, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

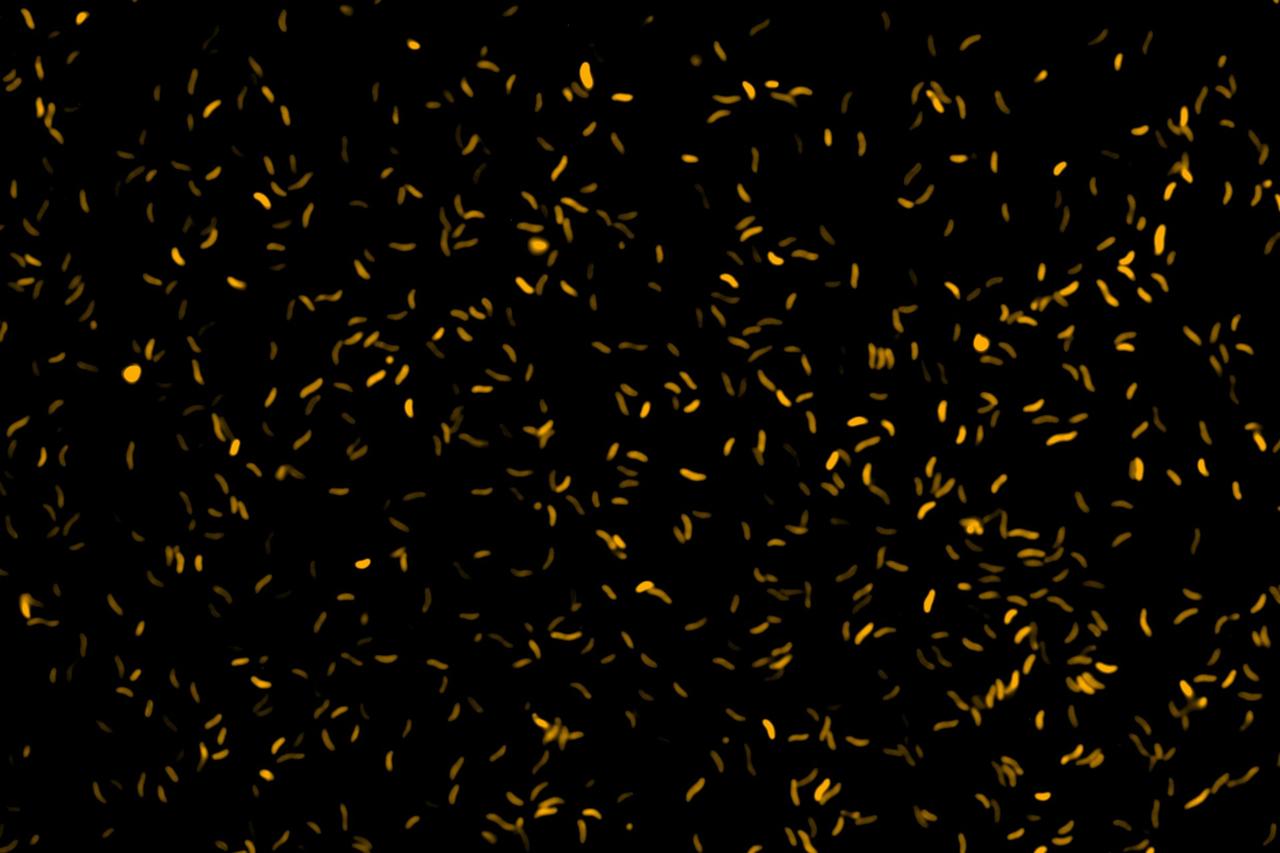

These bacteria thrive in warm, low-salinity environments, making the warming waters along Türkiye’s Marmara, Aegean, and Mediterranean coasts increasingly suitable for their proliferation. Recent scientific studies have confirmed the presence of Vibrio species such as Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus in Türkiye's coastal waters.

The primary health risk linked to Vibrio stems from its ability to enter the body through open wounds. Once inside, it can trigger severe infections, including necrotizing fasciitis—a rare but potentially fatal condition often described as the work of “flesh-eating bacteria.”

Urology specialist Dr. Ugur Aferin of Istanbul Florence Nightingale Hospital explains that Vibrio vulnificus, when in contact with damaged skin, can cause soft tissue infections that progress rapidly. He also warns that ingesting seawater contaminated with Vibrio cholerae—especially during recreational swimming—can result in cholera, a disease marked by severe diarrhea and dangerous fluid loss. Although cholera cases in Türkiye are rare, the risk cannot be dismissed entirely.

Vibrio-related illnesses are not confined to swimmers alone. The bacteria can also be contracted through consumption of undercooked or raw seafood, especially shellfish like oysters. When contaminated, Vibrio parahaemolyticus can lead to symptoms including abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever.

According to Dr. Aferin, the danger intensifies for individuals with compromised immune systems. In such cases, the infection can spread to the bloodstream, resulting in sepsis—a potentially fatal condition that demands immediate medical intervention.

In the context of urology, prolonged exposure to wet swimsuits, particularly after sea bathing, poses another health risk. Aferin notes that staying in damp swimwear increases genital moisture and warmth—ideal conditions for bacterial growth. This may facilitate the spread of Escherichia coli (E. coli) to the urinary tract, especially in women, increasing the likelihood of urinary tract infections. The effects may be more severe in those with weakened immunity.

Experts emphasize that artificial swimming environments are not exempt from microbial threats. Pools can harbor pathogens like rotavirus, hepatitis A, salmonella, shigella, and E. coli—especially when hygiene and chlorination are poorly maintained.

Children are particularly susceptible. Pediatric specialist Dr. Huseyin Yildiz cautions against allowing infants younger than four months to enter the sea, or younger than six months to enter pools. Their underdeveloped neck and head control, paired with higher risk of fluid and heat loss, make them especially vulnerable to illness.

If children already suffer from gastrointestinal issues or have open wounds, medical professionals strongly advise keeping them out of the water entirely.