A new academic study uncovered the enduring impact of Ottoman and Islamic culinary traditions on contemporary Greek cuisine, revealing how centuries of cultural interaction have reshaped the nation's culinary identity. The research, led by scholars from the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, explores how Islamic cooking techniques, ingredients and dining customs have been absorbed and adapted within Greek gastronomy.

The study combines historical analysis with fieldwork, surveys and interviews to demonstrate the depth of this culinary fusion. From the streets of Thessaloniki to the Muslim-majority region of Thrace, evidence of this shared legacy appears in both everyday meals and festive dishes.

According to the research, the period of Ottoman rule acted as a turning point for Greek cuisine. It introduced spices such as cumin, coriander and saffron into Greek kitchens, transforming flavor profiles. Coastal cities like Thessaloniki, historically home to diverse communities including Jewish and Muslim merchants, became centers where chefs reimagined traditional Ottoman dishes with Greek ingredients.

This culinary exchange is visible in seafood recipes that reflect both Islamic and Mediterranean influences—once status symbols in Ottoman courts, these dishes now define Greek coastal dining.

One of the most striking findings is the influence of Islamic festivals on Greek food customs. Shared celebrations like Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha have introduced festive dishes such as baklava into broader Greek culinary culture. These events, often featuring communal meals, highlight a philosophy of hospitality rooted in both traditions.

The layering of baklava—its phyllo dough and nuts—symbolizes the layered history of Islamic and Greek cultural exchange, making food a powerful vehicle for connection.

Islamic and Greek cuisines share a number of key ingredients, with olive oil serving as a culinary and cultural staple. Spices such as cinnamon, allspice and cardamom also crossed over from Islamic culinary traditions into Greek pantries.

Perhaps most notably, rice—once regarded with indifference—has evolved into a foundational component in Greek cooking, particularly in pilafs. These dishes have retained their Islamic roots while adopting local twists.

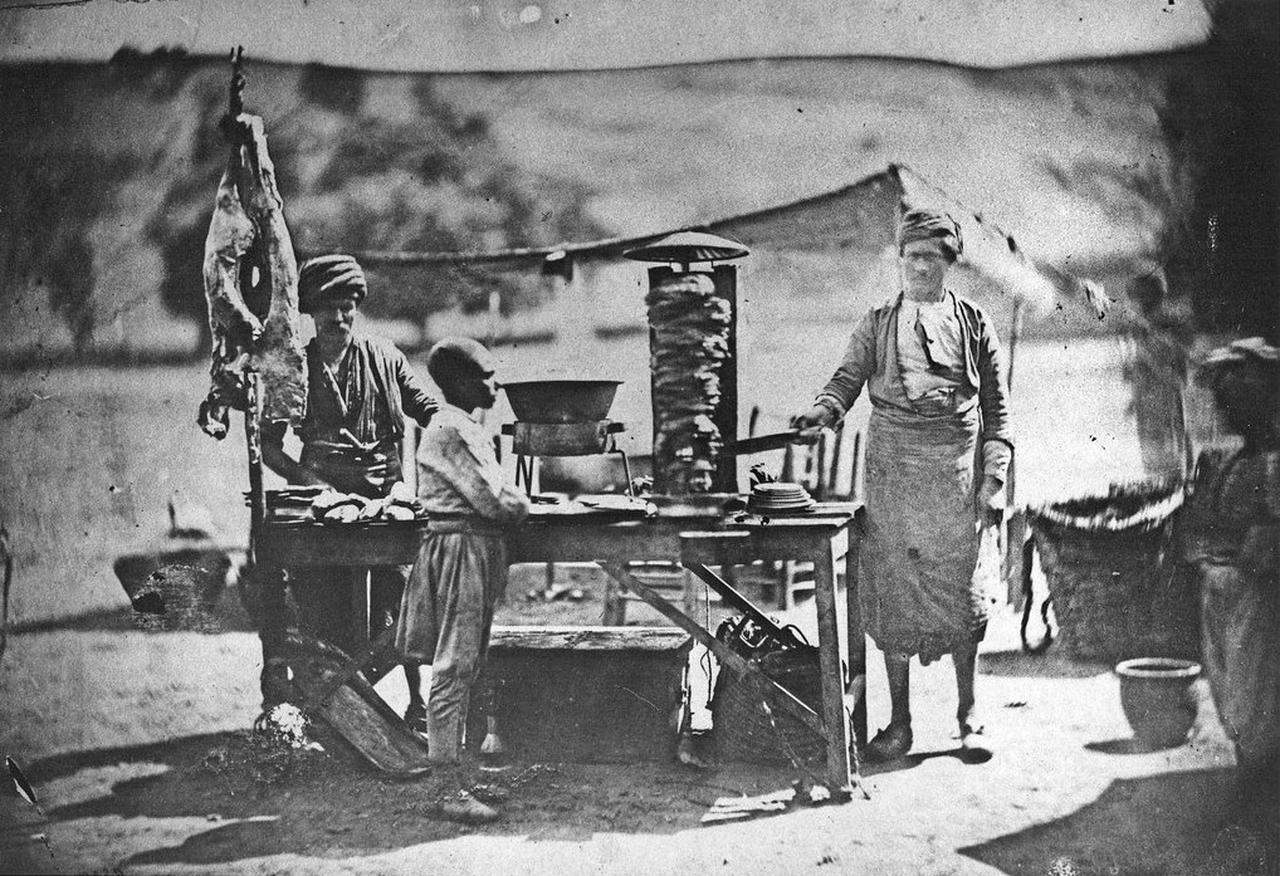

Modern Greek restaurants increasingly experiment with these historical influences. The doner kebab, an Ottoman staple, has been transformed into a Greek street food favorite. Fusion eateries embrace Turkish cooking techniques while maintaining distinctly Greek presentations, offering patrons a taste of shared heritage in each bite.

Street food festivals, such as those in the city of Chalkis, further showcase how local vendors reinterpret global dishes using Greek ingredients—a process known in cultural studies as “glocalization.”

The rise of social media has breathed new life into traditional recipes, with platforms like Instagram and TikTok helping young Greeks rediscover and reinterpret their food heritage. Female chefs and writers have played a key role in this revival, blending personal stories with historical narratives to engage new audiences.

This digital wave, described as a “neo-Ottoman” culinary movement in the study, underscores how old recipes gain fresh meaning when told through modern lenses.

In Thrace, where a significant Muslim population remains, the Islamic culinary heritage is still practiced in homes and local eateries. Here, traditional recipes are not just followed but passed down as a form of cultural storytelling. Each meal becomes a symbol of memory and identity.

These practices have proven resilient even in a globalized food world where many local traditions face the threat of standardization.

The researchers conclude that Greek cuisine continues to evolve through ongoing engagement with Islamic culinary traditions.

Chefs and home cooks alike are reinterpreting old dishes using new techniques while preserving their historical significance. More than anything, the study emphasizes that food remains a powerful medium for cross-cultural appreciation.