Europe is enduring another summer marked by extreme and persistent heat.

Successive heat waves in 2025 have pushed temperatures to record levels in France, Spain, Türkiye, Greece, Hungary and beyond, straining health systems, fueling wildfires and testing the resilience and sustainability of urban infrastructure.

The question remains: is this Europe’s new reality, or merely the calm before the next wave of the climate crisis?

The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre reports that surface temperatures in cities can be up to 10–15 degrees Celsius (50-59 degrees Fahrenheit) higher than in surrounding rural areas during the summer.

This is largely due to the urban heat island effect, in which materials such as asphalt and concrete absorb and retain heat, raising city temperatures by two to four degrees compared to the countryside.

Tall buildings, dense street networks and heavy traffic trap hot air and block cooling winds, especially in poorer neighborhoods where green spaces are scarce.

Why are urban heat centers a problem in Europe?

Almost 70% of Europe’s population lives in urban areas, making this a major public health concern. In Portugal, researchers from the NOVA National School of Public Health found hospital admissions rose by 18.9% during heatwave days.

“Especially the elderly with underlying health conditions, for example respiratory illnesses or cardiovascular illnesses, are worst affected,” said Niels Souverijns, a climate expert at VITO in Belgium, as reported by Euronews.

Nighttime offers little relief. Heat islands often persist after sunset, preventing the body from cooling during sleep and increasing risks to cardiovascular health.

Climate scientist Wim Thiery of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel warns that the problem is set to worsen as climate change drives hotter days and warmer nights.

This summer’s heat has broken long-standing temperature records.

Türkiye established a new all-time European temperature record in late July when the southeastern province of Sirnak recorded 50.5 °C, according to data from the Turkish State Meteorological Service.

In Bordeaux, France, the mercury reached 41.6°C, exceeding the previous 2019 high.

Other French cities, including Bergerac, Cognac and Saint Girons, also set all-time records. Parts of Spain and Portugal have reached 43°C–44°C, while the U.K. has faced its fourth heat wave of the season.

Extreme heat has amplified wildfire risks.

The U.K.-based Carbon Brief warns that Europe is the fastest-warming continent, with land temperatures rising about 2.3°C above pre-industrial levels, nearly double the global rate. The EU’s Copernicus climate service predicts 2025 will be one of the hottest years on record.

A recent study in Nature Communications by Wu, Wang, Ge and colleagues highlights the growing threat from compound day-night heat waves, which are periods when high temperatures persist both during the day and night. These events severely limit physiological recovery, increase cardiovascular strain and disrupt sleep.

The study projects that such heat waves will become more frequent and intense across Europe this century, affecting even northern and eastern regions historically spared from extreme heat. Aging populations in many countries will compound health risks, with older adults especially vulnerable.

Urban areas will face the worst impacts because of heat island effects, particularly at night. “We have to redesign cities to remove as much concrete as possible,” said Souverijns.

Solutions include planting trees, creating wind corridors, expanding shaded public spaces and increasing water features. Yet experts caution that adaptation alone is insufficient without rapid emissions cuts.

Data from the 2024 European State of the Climate report shows that last year was the warmest on record in Europe, with record sea surface temperatures and unprecedented numbers of extreme heat days.

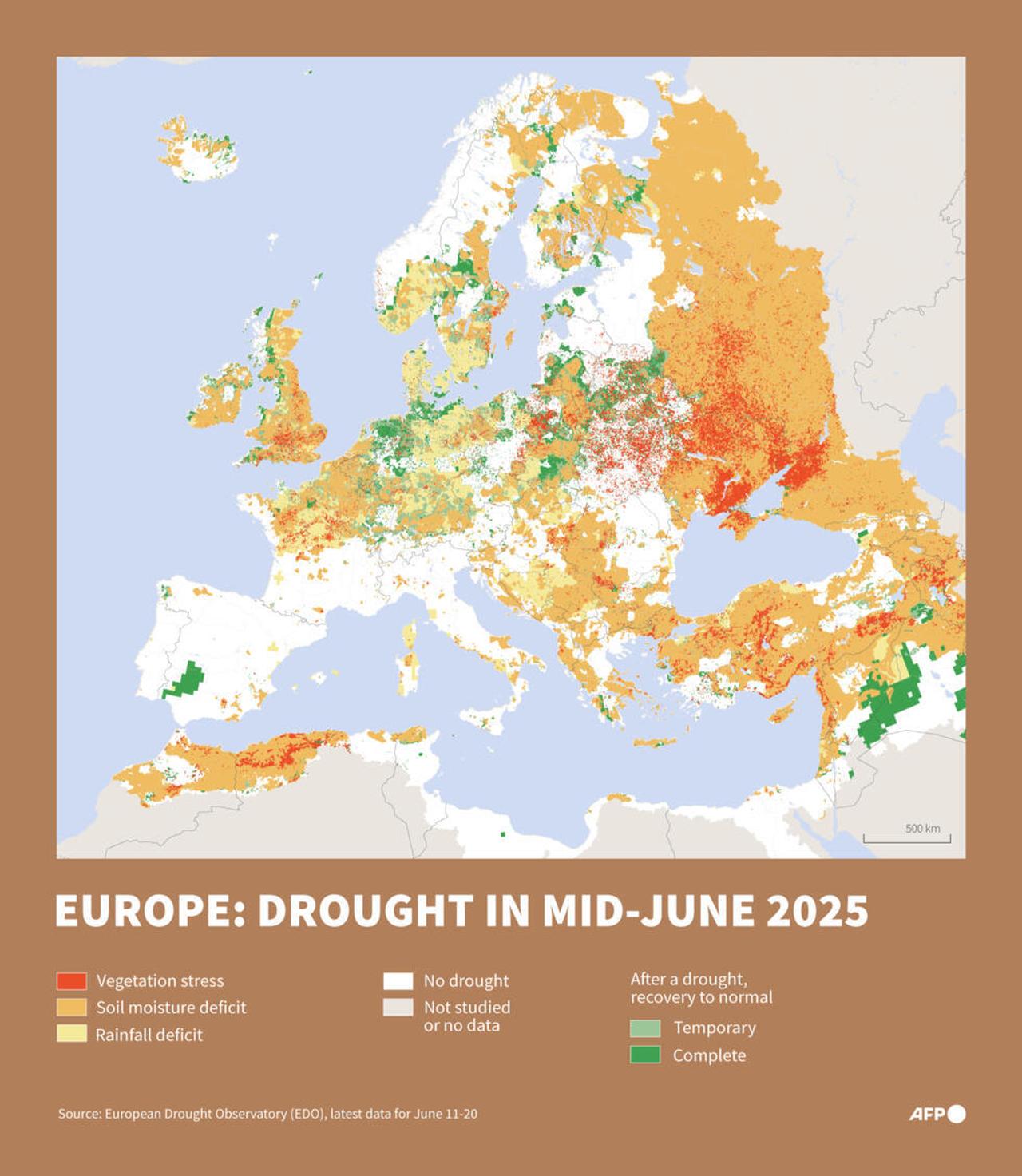

Glaciers in Scandinavia and Svalbard suffered their highest-ever annual mass loss. Southeastern Europe saw its driest summer in 12 years, while western Europe endured one of its wettest years on record.

Southern regions are also facing longer-term shifts. Researchers at the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya project that by 2050, parts of Spain and the Balearic Islands will transition to a steppe- or desert-like climate, with rainfall falling up to 20% and tropical nights increasing sharply.

The number of summer days over 25°C has already risen by 43% since the 1970s.

Türkiye is facing its own climate challenges.

A high-resolution ocean circulation model developed by Istanbul Technical University projects that, under the worst emissions scenario, the Black Sea’s average surface temperature could rise by up to 4°C by 2100.

Warmer waters will increase the intensity of storms along Türkiye’s northern coast, raising the risk of flooding, storm surges and coastal erosion. Higher sea levels could cause salinisation of farmland near the shore, threatening agricultural productivity.

Warmer seas will also affect marine ecosystems. Increased temperature and salinity could reduce fish populations, with more frequent marine heatwaves causing mass die-offs.

“The Black Sea may shift from being a living sea to a much less vibrant one,” Professor Mehmet Ilicak, told Anadolu Agency, warning that only global emissions cuts can prevent the worst outcomes.

Türkiye is also among the countries most at risk of severe drought.

A U.N.-supported report warns that 88% of the country is vulnerable to desertification, with rainfall projected to fall by up to 30% by the end of the century.

The U.N. report describes drought as a “silent killer” that depletes resources and worsens poverty and ecosystem collapse.

The 2025 winter was the driest in 24 years, with southeastern Türkiye receiving just 6% of its average January rainfall.

Across Europe, cities are experimenting with solutions to reduce heat stress, from shaded structures in Brussels to green roofs in Paris.

However, experts agree that mitigation, meaning cutting greenhouse gas emissions, remains essential. Without it, adaptation measures will be overwhelmed by the scale of warming.

The European Commission warns that without stronger action, climate damage to cities could be up to ten times worse by 2100. A continent-wide adaptation plan is under development, focusing on urban resilience, flood protection and sustainable energy use.

On the other hand, investment in water management, coastal protection and climate-resilient agriculture will likely be critical for Türkiye.

High-resolution modelling for the Black Sea, Mediterranean and Aegean could help forecast local impacts and guide responses. As Professor Ilıcak explains, “Even if Türkiye reduces its emissions, the Black Sea will not recover unless other countries act as well. This is a global responsibility.”

Can European cities adapt quickly enough to rising temperatures?

The summer of 2025 has seen successive, record-breaking heatwaves across much of Europe, with impacts ranging from increased hospital admissions to large-scale wildfires.

Data from the European Commission and Copernicus show that Europe is the fastest-warming continent, with land temperatures about 2.3°C above pre-industrial levels.

Researchers warn that compound day–night heatwaves are expected to become more frequent and intense, affecting both southern regions already accustomed to high temperatures and northern areas previously less exposed.

Urban heat islands, warmer nights and demographic trends such as population ageing are projected to increase vulnerability, while regional studies highlight additional risks including drought, sea level rise and ecosystem changes in countries such as Türkiye.