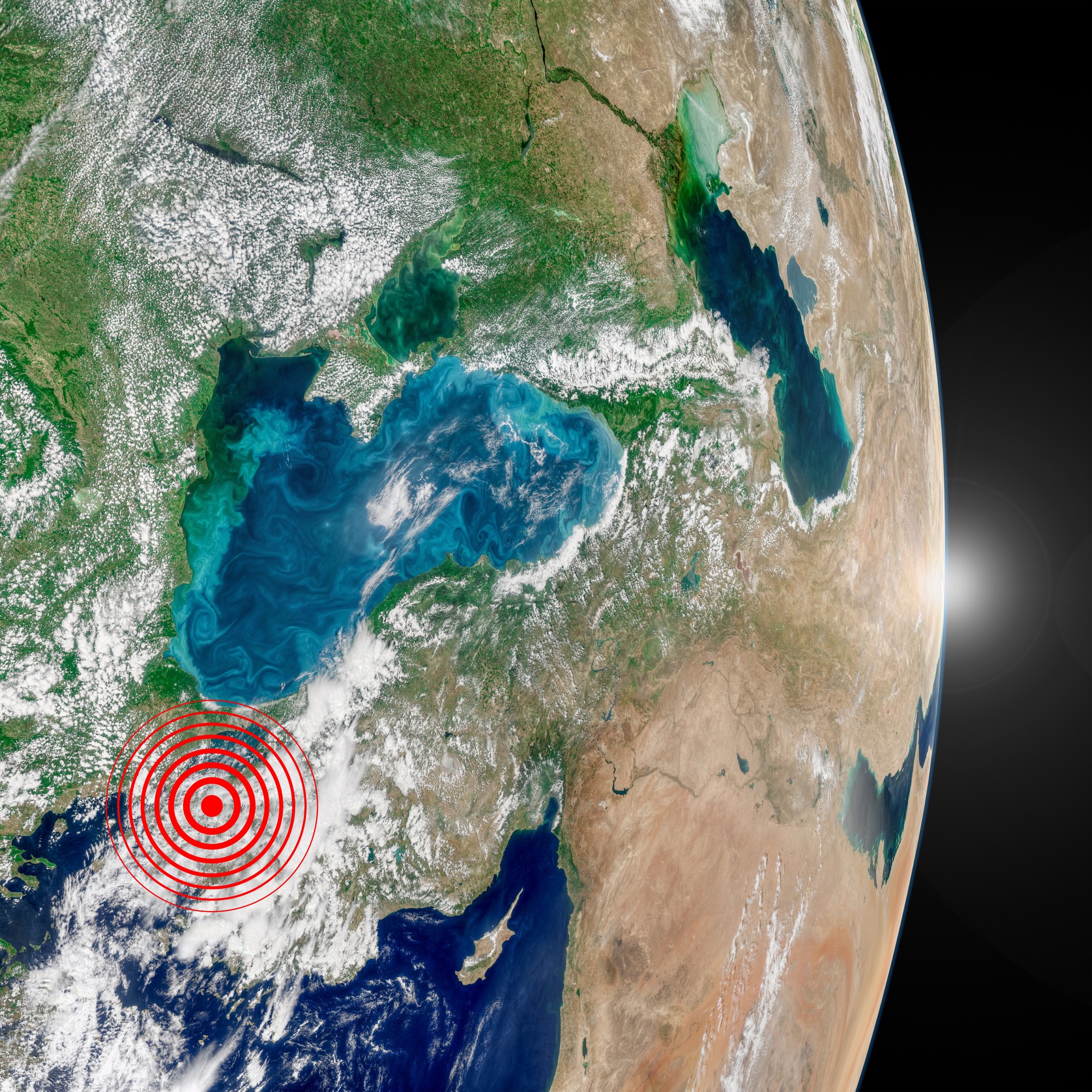

After the 6.1 magnitude earthquake in Balikesir’s Sindirgi district shook both the Aegean and Marmara regions, experts renewed their warnings about the expected Istanbul earthquake.

Speaking at a public awareness event hosted by Atasehir Municipality, earthquake scientist Naci Gorur said the North Anatolian Fault is among the most active in the world.

“This fault, wherever it breaks, targets its west for the next earthquake. It broke in Kocaeli in 1999. We are to its west. The probability of at least a 7.2 magnitude earthquake in Istanbul is very high,” he said.

Gorur explained that the fault produces major earthquakes about every 250 years.

“The last big earthquake happened in 1766. Add 250 years and you get 2016. Marmara’s time to produce an earthquake has run out. No amount of prayer can stop this mechanism. It happens according to the unchanging laws of nature,” he said.

He warned that the most severe destruction will occur on Istanbul’s European side, where the soil is young, water-saturated, and amplifies seismic waves.

“Residents on the coastline enjoy the view, but in a possible earthquake, the risks of acceleration and collapse are much higher,” he said. Gorur added that even the most solid buildings could sustain damage in an intensity 9 earthquake.

He stressed that the only way to prevent mass casualties is to create earthquake-resistant cities. He urged municipalities to take urgent action and called on voters to demand seismic safety commitments from politicians.

Gorur proposed that municipalities form six-person crisis teams that include coordinators for the public, infrastructure, building stock, ecosystem, and economy, all working on-site around the clock.

While Gorur warned of an urgent risk, Sener Usumezsoy told CNN Turk that Istanbul faces no imminent earthquake danger.

He argued that the Adalar fault and other segments often described as threats are not active. According to Usumezsoy, stress is building in other regions of western Türkiye, including areas between Manisa and Turgutlu, and the Alasehir and Sarigol region.

Usumezsoy said aftershocks from the Sindirgi earthquake could continue for two months and may trigger nearby faults such as Simav, Demirci, and Usak. He pointed out that some models linking Bursa to the North Anatolian Fault are incorrect and that no such fault exists in Bursa’s southern zones.

He explained that past earthquakes in the area, such as the 1968 Demirci quake, happened on smaller fault lines that do not produce the scale of a 7.6 magnitude event.

He added that the Kumburgaz segment had already broken and that the most active stress zones lie further south, making a large Istanbul earthquake unlikely in the immediate term.

As debate continues among experts, Istanbul’s seismic monitoring network is expanding to improve earthquake preparedness.

Bogazici University’s Kandilli Observatory operates 24 seismic devices across the city, measuring either the speed or acceleration of ground motion. These devices are installed in districts including Avcilar, Bakirkoy, Buyukcekmece, Kartal, Kilyos, Silivri, and Sile, as well as on the Princes’ Islands.

Officials say the data from these devices allows them to assess potential earthquake impacts in advance. This technology plays a critical role in planning and preparedness for the expected Istanbul earthquake. Nationwide, the Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD) operates 950 seismic monitoring stations, while Kandilli Observatory manages 309.