Independent theaters have become some of the most inventive cultural spaces in Istanbul. Some are hidden in basements, tucked inside old shops, or improvised in apartment blocks. They give voice to new playwrights, nurture young actors, and provide audiences with alternatives to the mainstream, while drawing on local or international stories. But they also operate on the edge of survival.

A new report by the Association for Communicating Social Good titled “Communication Habits of Theater Venues” reveals how these stages function behind the curtain. Surveying 68 independent theaters across the city, the study highlights an ecosystem that is both vibrant and precarious: creative in adapting to constraints, but constantly under threat from financial shortages, bureaucratic hurdles, and communication gaps.

The research focuses on the surviving theaters that the artistic environment of the city couldn't eliminate. One striking detail concerns longevity. More than half of the theaters interviewed (53%) were established during or after the pandemic (2020 and later), while 32% opened between 2013 and 2019. Not a single theater founded between 1991 and 2001 has survived to the present, and of those set up in the early 2000s, only five remain open today.

In today’s theater world, visibility is everything—and in Istanbul, visibility mostly means Instagram. The report found that nearly every independent venue uses the platform as its primary communication tool. For many, it has replaced posters, brochures, and even websites. Audience engagement is almost exclusively digital, and Instagram has become the ticket counter, noticeboard, and publicity office rolled into one.

Yet this dependency is risky. Algorithm changes or account hacks can derail months of preparation. Some theaters reported losing entire followings overnight due to technical issues. With no backup strategies in place, visibility rests on a fragile digital infrastructure controlled by external platforms, mostly managed by young interns or staff themselves.

Theaters know that sustained communication requires strategy, but very few can afford it. Almost 90% of independent venues receive no sponsorship or external funding for outreach. With limited staff, directors and actors often double as publicists, juggling press releases with rehearsals.

The result is improvised communication. Media coverage depends on personal ties rather than structured relationships, and audience development is intuitive rather than data-driven. Many describe the biggest challenge as time: every hour spent on publicity is an hour not spent on production.

On the other hand, systematic crisis management is virtually absent. Most responses are reactive: reopening hacked accounts, reposting damaged flyers, or ignoring harassment campaigns. In the absence of formal protection or support, survival often depends on improvisation and ad hoc measures.

Volunteerism is the lifeline of independent theaters, but also their greatest weakness. According to the study, nearly three-quarters of venues employ no full-time staff at all. Instead, work is shared among freelancers, part-timers, or unpaid volunteers.

This model fosters flexibility and solidarity, but it comes at the cost of continuity. Without stable staffing, institutional memory is lost, making it difficult to build consistent audience relationships or long-term strategies. Artists often speak of “doing everything”—performing, producing, managing finances, even cleaning the stage. Their resilience keeps the curtain up, but burnout looms large.

Considering that theater is an endeavor of tradition, it is unclear how far one can rise through individual sacrifices alone.

Audience numbers alone expose another challenge. In the 2023–24 season, the average annual audience across 52 surveyed theaters was around 10,000, but the median was only below 4,000. That is, while a few larger venues pull up the average, most theaters remain far below that threshold.

While Istanbul is a city of over 20 million people, many theaters struggle to fill even small halls. Nearly 40% reported reaching fewer than 2,500 spectators across an entire season. A third failed to draw even 1,000 as their audience.

Only one in five theaters managed to surpass 10,000 spectators, and those were mostly high-capacity venues or those operating within malls.

The majority operate on shoestring audiences, where the difference between 800 and 1,200 spectators can determine whether they survive another year.

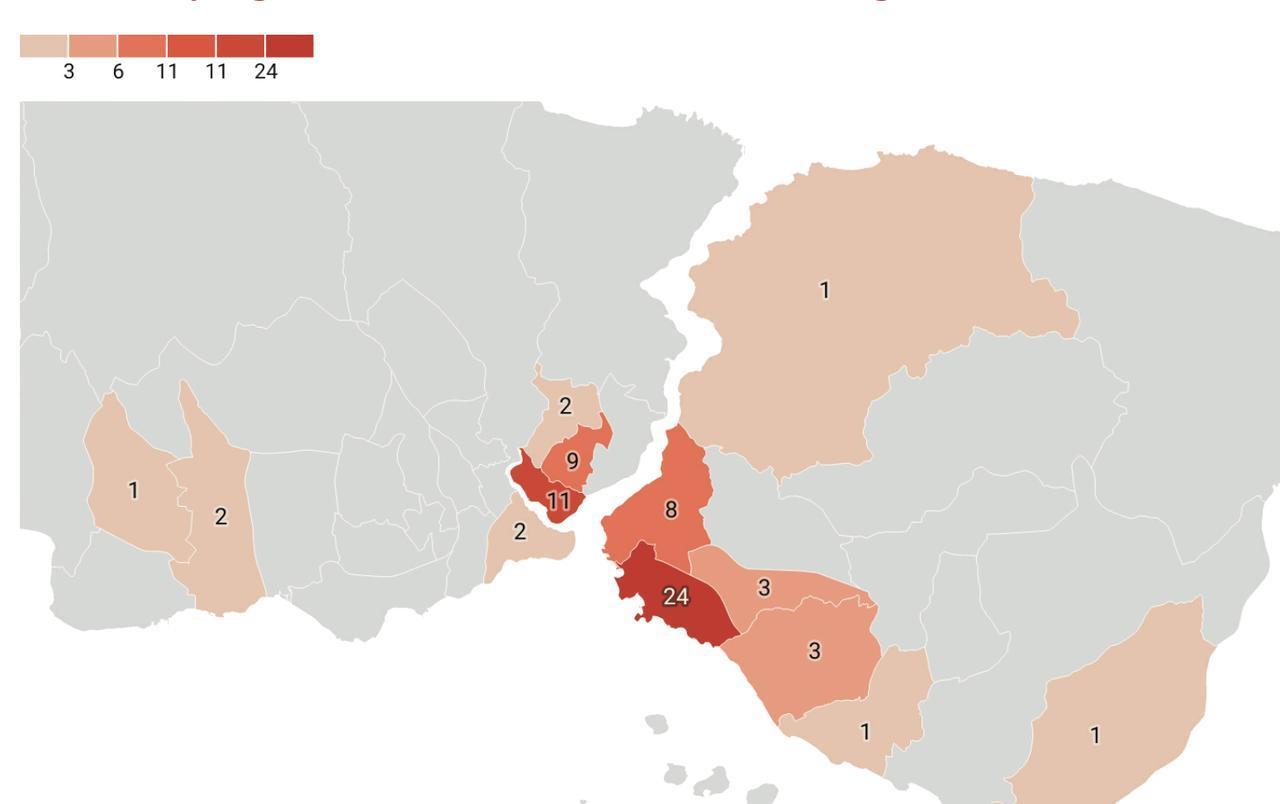

Geography matters. The report shows that independent theaters are clustered in a handful of central districts. Kadikoy leads with 24 venues, followed by Beyoglu. Together with Sisli and Uskudar, these districts host over three-quarters of all independent stages.

Other parts of the city are cultural deserts. Peripheral or central, most populous districts like Kartal, Kucukcekmece, Avcilar, or Fatih have only one or two venues. The uneven distribution highlights the barriers of accessibility: for much of Istanbul’s population, attending an independent play still requires crossing the city.

What independent theaters lack most is not creativity but support. The report calls for practical reforms that could ease financial and communication burdens. Municipalities, the report suggests, could allocate public advertising spaces for theater use, purchase bulk tickets to guarantee audiences and for people to have access to culture, or coordinate programming calendars to avoid overlap.

Indirect support measures such as tax breaks or subsidies for venue rentals could also free up resources for communication and audience engagement.

These proposals stop short of calling for direct subsidies but emphasize the need for recognition of independent theaters as cultural institutions, not just entertainment businesses.

Perhaps the strongest demand of the report is for a Theater Law, which comes as a framework that would formally recognize independent stages and enshrine their role in cultural policy. Without such recognition, theaters remain invisible in policymaking, excluded from institutional support mechanisms available to other cultural actors.

Advocates argue that legal recognition would not only stabilize finances but also professionalize communication. It would give theaters access to sponsorship incentives, structured media relations, and protection against arbitrary closures.

The report also highlights how theaters attempt to manage survival through market strategies. Around 42.6% of theaters use multiple ticketing platforms at once, both to diversify audience reach and to avoid dependency on a single intermediary. Many criticize conditions imposed by platforms, such as “exclusive cooperation” clauses. One common complaint is that theaters can no longer access their own audience data: “We used to know who bought tickets when we sold them ourselves. Now, we’ve lost the ability to track our own viewers.”

Despite their fragility, independent theaters remain central to Istanbul’s cultural life. They serve as rehearsal hubs, training grounds for young actors, and neighborhood cultural centers. They diversify the city’s cultural production in ways that commercial or state-backed venues cannot.