Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) leader Devlet Bahceli closed his party’s Tuesday parliamentary group meeting with a carefully worded message that quickly drew nationwide attention: “Our decision is clear until Anatolia finds peace, Ocalan has hope, the Ahmets return to office, and Demirtas returns home.”

For much of the past year, developments in northern Syria were widely viewed as the main obstacle to progress on the domestic Kurdish file.

Ankara’s security concerns regarding YPG and SDG structures, combined with uncertainty over post-conflict governance, had frozen political maneuvering at home.

That constraint now appears to have eased. Turkish officials and political observers increasingly describe the Syria file as largely managed, particularly following new security arrangements and integration mechanisms on the ground. With that burden reduced, attention has shifted back to domestic legal and political steps.

By framing the process as ongoing and settled in principle, the party leader signaled that external developments should no longer be used as justification for indefinite delay.

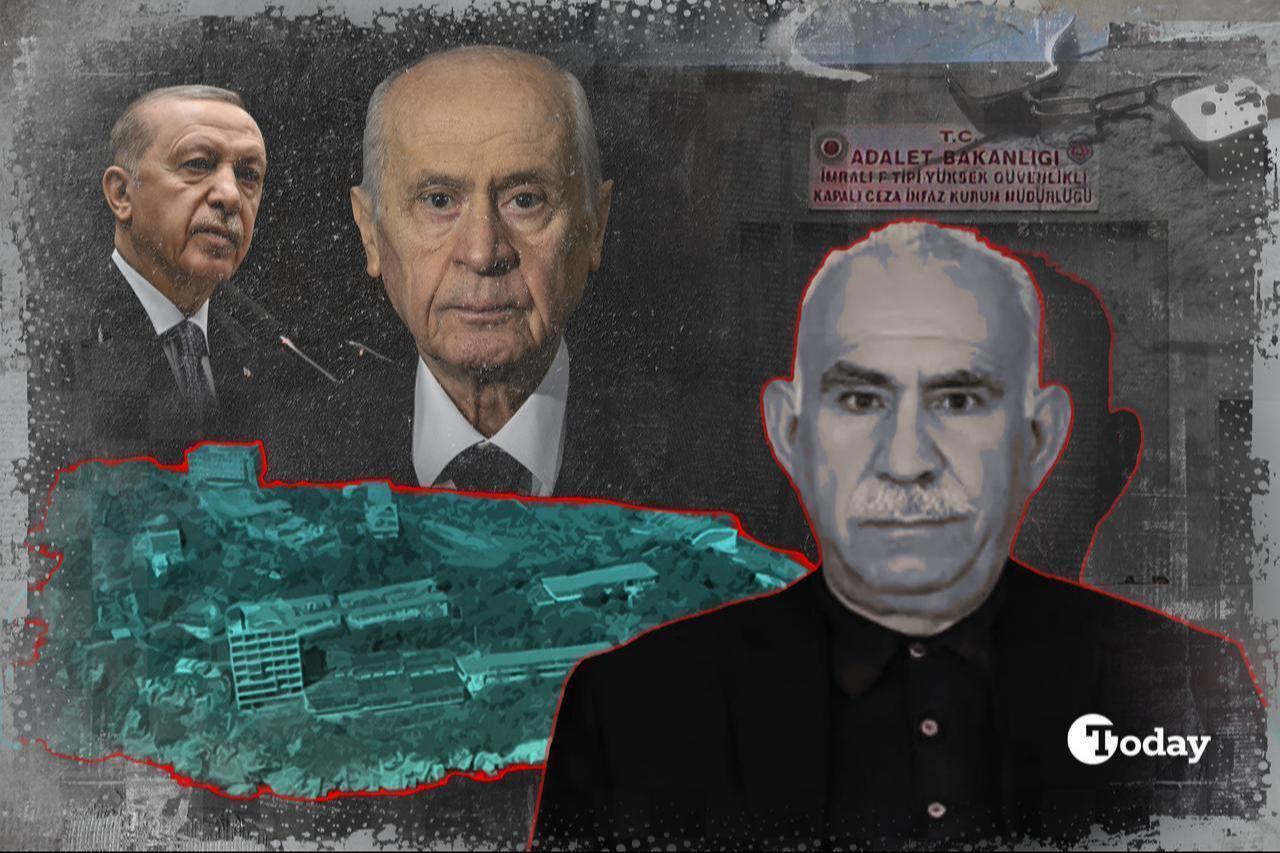

One of the most sensitive elements of Bahceli’s statement was his reference to Abdullah Ocalan and the concept of “hope.” The term is closely associated with the “right to hope,” a principle rooted in European human rights jurisprudence that argues life sentences should not amount to irreversible punishment without review.

Bahceli has previously argued that Ocalan could be entitled to this right if he contributes to the dissolution of the PKK. In the current debate, the emphasis appears to be less on release and more on the normalization of conditions and legal status within existing frameworks.

Political circles in Ankara have pointed to recent improvements in communication and visitation conditions as evidence that limited steps are already underway. These include expanded access to lawyers and controlled channels of contact.

Another key pillar of Bahceli’s message concerned elected local officials removed from office and replaced by state-appointed trustees. His reference to “the Ahmets” was widely understood as pointing to Ahmet Ozer and Ahmet Turk, two figures whose cases have become emblematic of the trusteeship debate.

Ozer, a member of the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), was suspended from office and arrested in 2024 while serving as mayor of Istanbul’s Esenyurt district over alleged links to the PKK.

Turk, a veteran Kurdish politician, was removed from his post as mayor of Mardin the same year for similar allegations. He had been elected under the banner of the Kurdish-oriented Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party).

By invoking these cases, Bahceli appeared to acknowledge that the peace process cannot advance while questions over elected representation remain unresolved.

Selahattin Demirtas, former co-chair of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), has been imprisoned since 2016 and was later sentenced on charges related to the deadly 2014 Kobani protests. His case remains one of the most closely watched by international legal institutions.

Bahceli’s reference to Demirtas “returning home” was interpreted not as an immediate signal of release but as a nod to broader debates over compliance with European Court of Human Rights rulings and the application of the rule of law.

Within this framing, Demirtas’s situation is increasingly treated as part of a systemic legal question within the government’s “terror-free Türkiye” narrative, rather than as an isolated political exception.

However, in the second half of 2025, numerous articles and reports—including in pro-government newspapers—predicted that decisions paving the way for Demirtas’s release were imminent. None of these forecasts altered reality, and Demirtas remained in prison.

At one point, several reports even claimed he would be released over a particular weekend. No such release occurred, and no formal update followed either that weekend or in the period afterward.

The remarks of the nationalist party’s leader also stood in quiet contrast to statements made just three weeks earlier by Justice and Development Party (AK Party) parliamentary group chair Abdullah Guler, who said there was “no item such as an amnesty for Ocalan on our agenda.”

The discrepancy highlighted ongoing uncertainty within the governing bloc over the scope and sequencing of potential steps.

While this does not amount to an open rift, the difference in emphasis suggests that consensus within the People’s Alliance is still evolving.

Parliamentary mechanisms, including the possibility of new commissions, are increasingly discussed as tools to manage this process.

The key government ally has long positioned himself as an early risk-taker on the issue. With Syria’s impact diminished, the government currently appears to have limited incentive to accelerate further steps, and deeper engagement may carry higher political costs than continued caution.

In the coming days, MHP members will have an opportunity to push these goals within parliamentary commission work and frame them as formal party policy.

How much of Bahceli’s Tuesday speech is carried into that arena will offer a clearer indication of how seriously the party intends to pursue these three objectives.