In recent months, a peculiar detail has caught the eye in Türkiye’s headlines. Several high-profile murders—ranging from the killing of Hilal Ozdemir to the murder of Italian-Turkish national Mattia Ahmet Minguzzi in Istanbul, the double homicide of Ilayda Alkas and Helin Eren in Diyarbakir, and the shooting of school principal Ibrahim Oktugan in Eyupsultan—have shared an unexpected commonality: suspects sporting the same haircut.

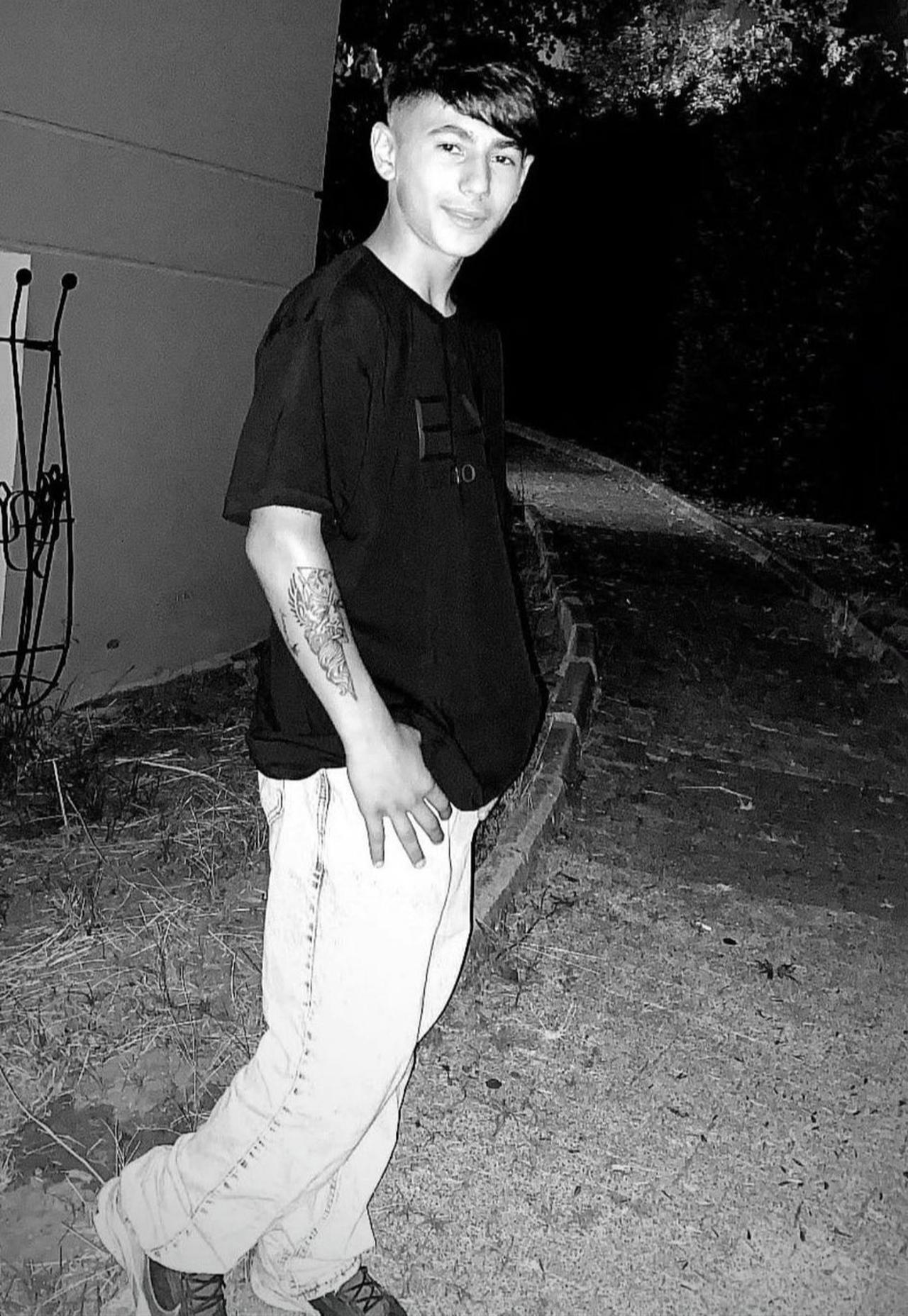

Known locally as tas tirasi (bowl cut fade) or the “Turkish Edgar Cut,” the style features closely cropped sides with the top left longer.

The visual pattern across unrelated cases has fueled speculation about whether this haircut has become more than a fashion statement—possibly evolving into a symbol of youth subcultures linked to violence.

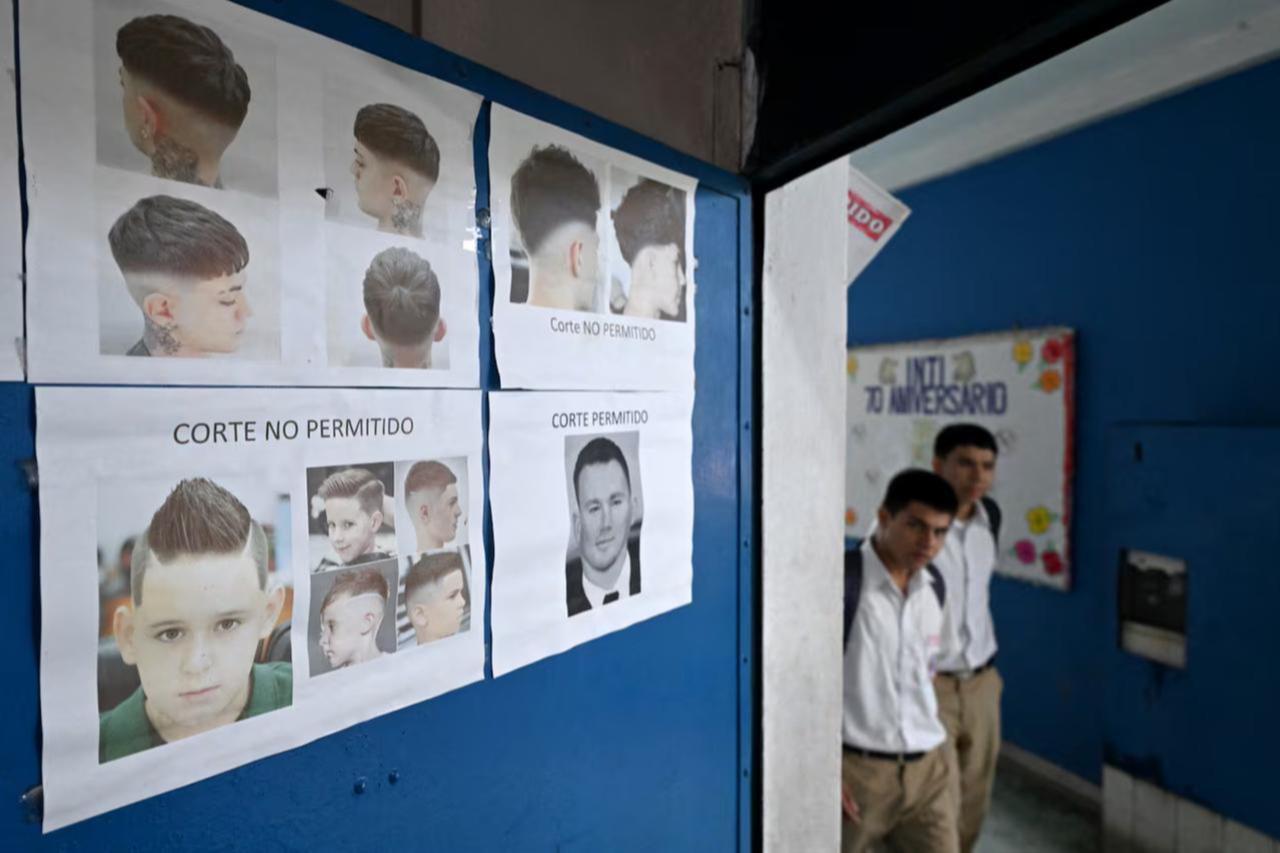

Earlier this month, one public school in Türkiye formally banned what it described as the “Turkish-style Edgar Cut,” informing students they could no longer attend class with this haircut.

The decision sparked debate on social media, reflecting wider unease about the style’s associations and its spread among adolescents.

For specialists, the repeated presence of the bowl cut among perpetrators is difficult to dismiss as a mere coincidence.

Neslihan Inal, head of the Turkish Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, told local media that symbolic markers often emerge in criminal or semi-criminal youth circles.

“Throughout the world, gangs adopt their own signs—haircuts, tattoos, and clothing codes—that serve as visible indicators of belonging,” she explained.

“When we look at the perpetrators of these violent crimes, each one has tattoos and prefers the Turkish Edgar. This cannot be coincidental. In adolescent culture, appearance is a way of saying, ‘I am one of you.’”

At the same time, Inal is careful to underline that hairstyle alone is not predictive of criminal behavior. Adolescents often use hair, clothing, or accessories simply to experiment with identity.

The concern, she noted, is that within violent circles, such signals can become symbolic tools of cohesion and recognition.

From the vantage point of forensic medicine, the phenomenon is not unprecedented. Nevzat Alkan, a professor at Istanbul University’s faculty of medicine, said the trend reflects a broader pattern of style codes within youth subcultures.

“Today, we clearly see a single haircut model dominating gangs and some adolescents. This is a subject worth academic study,” he said. “These styles are not static—they shift with trends. In the past, for example, Neo-Nazi and skinhead groups used shaved heads as a symbolic identity marker within their subcultures.”

Alkan emphasized that international literature does not establish any scientific correlation between hairstyle and criminality.

Still, he argued that the recurrence of such a visual cue in violent cases makes it a phenomenon that criminologists and sociologists cannot afford to ignore.

What is notable in Türkiye, observers say, is that the haircut’s popularity is strongest in provinces and districts with the lowest socioeconomic development levels.

The style has spread in disadvantaged regions where youth often search for ways to assert identity and belonging.

The debate reflects deeper anxieties over how Turkish youth navigate identity, peer pressure, and belonging in an era of rapid social change.

Experts point out that adolescence is a time when external appearance often carries heightened meaning.

Tattoos, clothing, or hairstyles can function as badges of solidarity, particularly in groups that feel marginalized or seek to project toughness.

“In these cases, we are not just looking at haircuts,” Inal said.

“We are looking at how young people choose symbols that reinforce their sense of community, even when that community is bound by violent behavior.”

The role of social media also looms large. Stylized looks, from fashion trends to haircut patterns, spread rapidly online, where they can gain currency as emblems of defiance or group identity.

When reinforced within delinquent peer groups, such symbols may inadvertently acquire an association with aggression or crime.

This is not the first time such a phenomenon has surfaced internationally.

In El Salvador, authorities moved to ban the style in schools in recent years, concerned about its links to gang identity.

In Japan, certain symbols tied to organized crime syndicates have also been subject to restrictions. Yet unlike El Salvador or Japan, Türkiye’s case is different: the haircut has not been formally associated with any single group, gang, or criminal organization.

Instead, it circulates more broadly as a youth trend that, in certain cases, overlaps with violent behavior.

For some observers, the issue is less about style itself and more about incentives. In El Salvador and Japan, political and social authorities moved proactively to stigmatize and marginalize certain symbols, hoping they would fade away under public pressure. Türkiye’s case is more complicated. In some circles, the haircut is used provocatively, even as a prelude to racist posturing, while in others it speaks more about socioeconomic realities than ideology. The spread of the “Edgar” or bowl cut in Türkiye’s least developed districts illustrates how style can mirror broader social divides.

Moreover, the model is not confined to Türkiye or El Salvador. Across Latin America, the same cut is widely seen in music, sport, and popular culture, far removed from crime. This raises a central question for Türkiye: will the struggle be waged against the haircut itself, against the incentives that allow it to thrive, or against the deeper conditions of poverty and uneven development? The answer may determine how this debate evolves in the years ahead.

The recurring appearance of the bowl cut among suspects underscores broader concerns over youth dynamics in Türkiye. Rising cases of youth-involved violence, coupled with visible subcultural markers, suggest a need for closer study of how identity, peer groups, and violence intersect.

Experts agree that the haircut itself does not predispose anyone to crime. But in a society where visual cues can be quickly politicized or stigmatized, their adoption by violent offenders highlights the role of symbols in shaping group belonging. Whether the Turkish way of Edgar cut becomes entrenched as a subcultural marker—or fades as trends shift—may depend less on fashion than on how Turkish society addresses the deeper currents of alienation, identity, and youth violence.