This week, Türkiye’s Parliament rejected a bill that would have provided free school lunches to students. Critics called the proposal an “unnecessary burden” on the state budget, but economists point out that the real weight lies elsewhere—in the long-term social and economic losses of not investing.

Evidence from academic research suggests that expanding free school meal programs generates about 1.5 times the economic return for every £1 spent, thanks to improved health, attendance, and learning outcomes.

The same logic applies to broader education policy. An October joint report by the Turkish Industry and Business Association (TUSIAD) and the Education Reform Initiative (ERG) warns that Türkiye’s education financing structure—already under strain—risks missing its moment.

Over the past decade, the country has quietly rewritten the grand strategy behind its public education budget: shift more of the burden onto citizens, and let the state cover the rest. Scholarships and equality of opportunities have steadily narrowed, and the early effects of this shift are now becoming impossible to miss.

With one-third of its population under 14 and its “demographic window” beginning to narrow, Türkiye is at a crossroads: it can either invest now in inclusive, well-funded education or face the compounded costs of inequality later.

The report’s fiscal findings are stark. Only 2.6% of Türkiye’s gross domestic product (GDP) goes to education—well below the global average of 4.5% and the U.N.’s target range of 4%–6%. Education’s share of total government spending stands at 10.6%, far short of the recommended 15%–20%.

This funding gap has shifted the burden onto households. In 2022, public sources covered 78.9% of total education spending, while families contributed 20.3%. In practice, this means that access to quality schooling is increasingly determined by a family’s ability to pay, through private tutoring, school meals, transport, and extracurriculars.

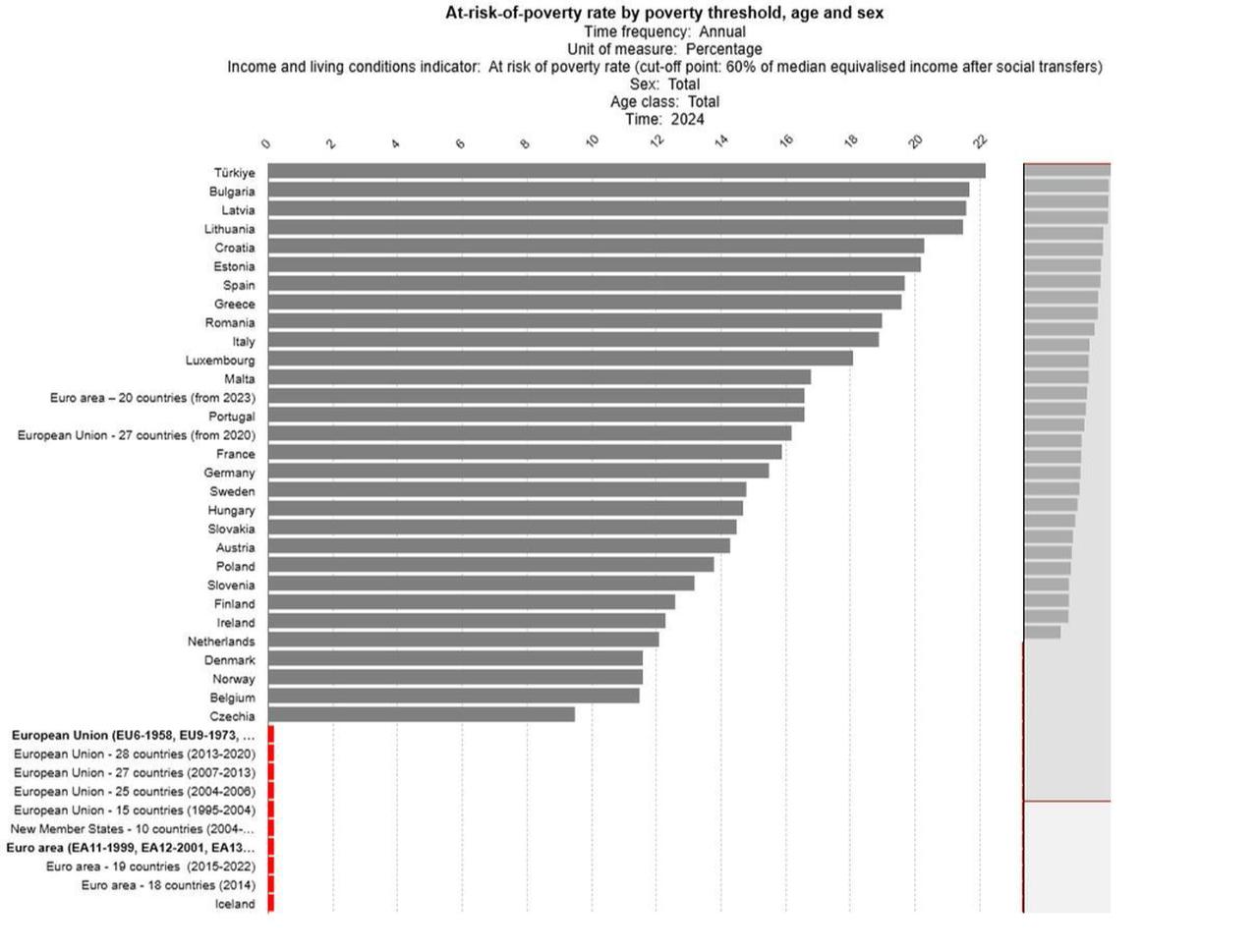

This load borne by households, according to the findings, makes Turkish families contribute nearly one-fifth of total education spending, one of the highest shares in Europe. The report notes that the situation basically translates into unequal access and growing social divides.

For a solution, the authors urge the government to introduce targeted support programs, including free school meals, transportation assistance, and need-based scholarships, to relieve families and prevent learning disruptions linked to poverty. Expanding such measures, they argue, is not welfare but strategy—a way to keep education accessible and socially cohesive.

The imbalance is compounded by how resources are distributed. Just 7% of the education budget goes to preschool, while about one-third is spent on higher education—one of the highest ratios in the OECD. With preschool neither free nor mandatory, inequality begins early and tends to persist. Per-student spending, adjusted for purchasing power, is roughly a third of the EU average, leaving classrooms crowded and teachers overextended.

At the governance level, the report advocates for participatory budgeting, ensuring that teachers, parents, civil society groups, and local communities have a voice in how education resources are allocated. Transparent publication of budget data by region and level of schooling is cited as essential for accountability.

Despite the odds, one piece of good news stands out: while education spending accounted for just 10% of total government expenditure in 2023, the 2025 budget plan is set to reach 15%—the threshold value outlined in the Education 2030 Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action.

The February 2023 earthquakes forced an abrupt reshuffling of the national budget. Education spending rose by 25% in real terms that year, but much of the increase went to reconstruction, housing, and emergency response. The share of education in total government spending remained static at 10%.

The report warns that post-disaster priorities—while urgent—have delayed necessary reforms in school infrastructure, learning recovery, and psychosocial support. As the immediate crisis response gives way to reconstruction, education funding must shift from emergency relief to resilience and quality-building.

Without multi-year budget commitments, analysts caution, Türkiye risks repeating a familiar pattern: short-term surges followed by long-term stagnation.

The findings suggest that Türkiye’s heavy reliance on household contributions, limited capital investments, and declining early childhood spending are undermining long-term goals of equity and competitiveness. As the country’s once-favorable demographics begin to shift, the report delivers the message that Türkiye’s economic and social trajectory will depend on how—and where—it spends on education in the next few years.

At the heart of the report is a simple proposition: investing in the earliest years of education delivers the highest return. Yet Türkiye remains one of the few OECD countries where preschool at age 5 is neither free nor compulsory.

In 2023, only 7% of public education resources went to early childhood programs, compared with over 21% for secondary and 33% for tertiary education. The imbalance undermines efforts to ensure equal starting conditions and narrow learning gaps.

One in three Turkish students reports attending school without breakfast, and nearly one in five says they went hungry at least once in the past month due to lack of money. These figures, the report argues, illustrate how socioeconomic inequality has become one of the education system’s defining features.

To address this, the study recommends making preschool universal and free, expanding independent kindergarten infrastructure, and reallocating a portion of higher education spending to early and primary levels. At the same time, capital investments should prioritize digital infrastructure, disaster resilience, and school modernization—particularly in disadvantaged and rural areas.