The idea of observing marginalized communities for leisure is not new. According to urban sociologist Ozgur Ozturk, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, European and American exhibitions displayed colonized peoples in so-called “human zoos,” where cultural difference was consumed as entertainment. Today, the logic of these spectacles echoes in “ghetto tourism,” a phenomenon that has become increasingly popular not only in Latin American favelas but also in parts of Istanbul such as Tarlabasi/ Beyoglu.

These tours are marketed as authentic cultural encounters. Visitors are guided through impoverished neighborhoods, sometimes by locals themselves, and are offered the chance to “experience” a different side of the city. Much like the favela tours in Rio de Janeiro, where tourists ride jeeps through narrow alleyways to observe daily life, Istanbul’s versions frame poverty as a consumable experience. The poor are no longer invisible; they are staged as part of the city’s cultural landscape, their environment turned into an urban safari.

Proponents argue these tours provide opportunities for disadvantaged communities to showcase their culture, generate income, and foster dialogue between social classes. Yet critics see them as exploitative. By turning hardship into spectacle, they risk reinforcing social distance rather than bridging it. The dynamic reduces inequality to entertainment, where poverty becomes an “authentic” product for middle-class and foreign consumption.

The backdrop to this phenomenon lies in Türkiye’s urbanization story. Since the 1960s, waves of migration from rural areas to cities created vast informal settlements, particularly around Istanbul. With inadequate infrastructure, limited services, and high unemployment, these neighborhoods became symbols of urban poverty.

By the 2000s, urban transformation projects sought to modernize cities but often displaced vulnerable groups, further entrenching social divides. However, the very same years for the nation witnessed a relative democratization, and the masses of new urban reality, who had previously been rendered invisible particularly in the media, gradually became more visible as they gained more political power.

As disadvantaged communities became physically more distant from middle- and upper-class lives, they simultaneously grew more present in the cultural sphere. Popular culture began to turn urban poverty and slum life into recurring themes, repackaging inequality as aesthetic content. This mirrors global trends, where marginalized neighborhoods are consumed not only through tourism but also through music, fashion, and film.

In Türkiye, the cultural representation of poverty has evolved alongside shifting social and economic realities. The “dangerous neighborhood” has become a brand of its own, feeding a cycle in which marginalized communities are distanced in real life but symbolically omnipresent in entertainment.

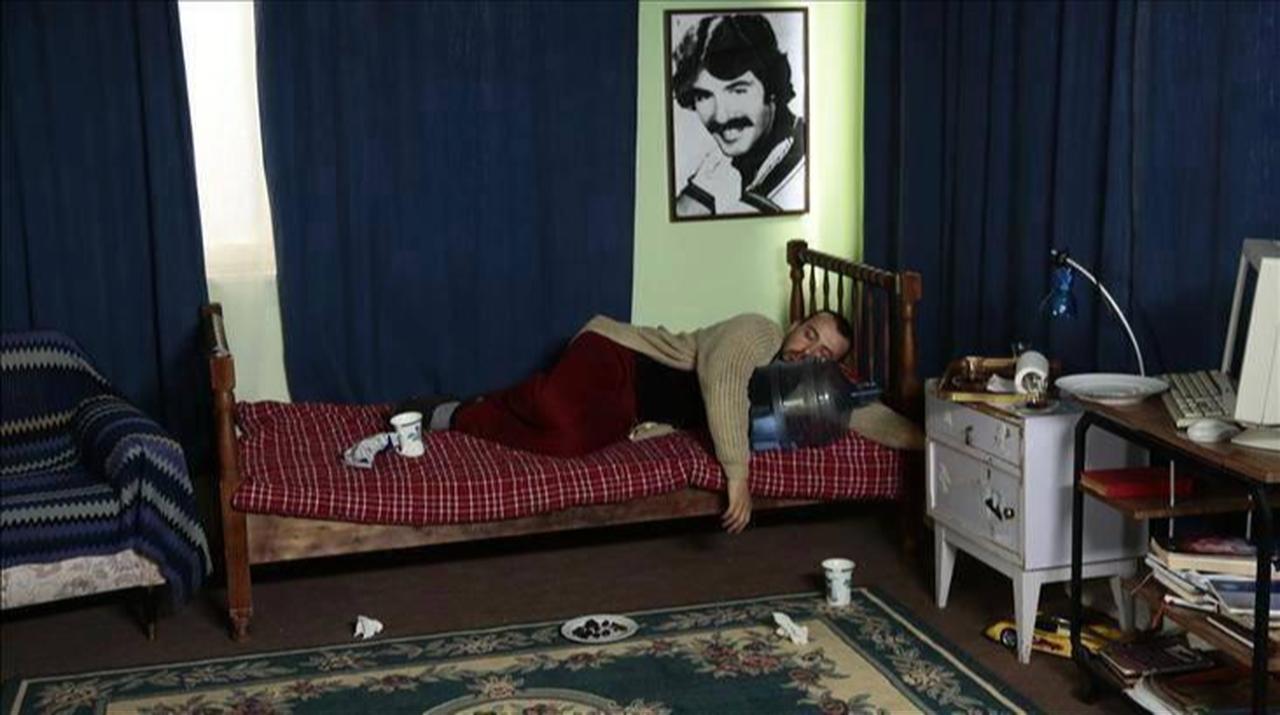

Music has been one of the most powerful mediums through which poverty and urban inequality are aestheticized. In the 1970s and 1980s, arabesk music gave voice to rural migrants grappling with hardship in big cities. Artists like Orhan Gencebay, Ferdi Tayfur, and Muslum Gurses became icons of an urban underclass struggling with poverty, exclusion, and fatalism. Their songs portrayed resignation, moral dignity of labor, and bitterness toward wealth, narratives that resonated with millions living on the margins.

However, the general perception was that the Turkish elite looked down on these artists and their listeners. Despite being listened to by a large enough audience to be considered mainstream, the figures were excluded by the established art community and the educated segment of the society.

Türkiye has overcome these challenges, and the lower income segments of society have become much more visible and respected in the arts and media circles.

Today, that space is increasingly occupied by rap and trap music. Streaming platforms in Türkiye are dominated by artists such as Uzi, Cakal, Lvbel C5, Blok3, and Poizi whose lyrics often highlight neighborhood pride, social exclusion, crime, and defiance. Unlike arabesk, which framed poverty in terms of struggle and destiny, contemporary rap frequently celebrates toughness and survival in disadvantaged areas, mixing pride with critique.

Digital media has played a key role in this transition. Platforms like TikTok allow performers from poor neighborhoods to bypass traditional music industries and present their realities directly. As a global trend, these tools also enabled the voices speaking for marginalized communities with a stage, but it has also commodified their imagery. Poverty is no longer confined to the neighborhoods where it originates, but it is repackaged and sold in cafes, clubs, and fashion across the country.

The consumption of poverty extends beyond music. Television series such as Cukur and Sıfır 1 have turned disadvantaged neighborhoods into cultural phenomena. These shows depict crime, community solidarity, and anti-heroes, offering dramatized versions of urban marginality that resonate widely. Their imagery travels beyond screens, appearing in tattoos, t-shirts, and social media memes.

Independent productions also highlight this trend. Low-budget series produced by residents of disadvantaged areas gain millions of views online, sometimes being picked up by major streaming platforms. Documentaries, YouTube vlogs exploring poor neighborhoods and their residents’ lives have found receptive audiences, further integrating poverty into mainstream cultural consumption.

Yet these portrayals come with contradictions. While stylized depictions of poverty are consumed enthusiastically in middle- and upper-class spaces, real-life encounters with violence or hardship in these same neighborhoods provoke fear and condemnation. The romanticization of “dangerous neighborhoods” in fiction coexists with social consensus to limit the public visibility of the poor in daily life.

As disadvantaged neighborhoods become fixtures in popular culture, poverty is increasingly stripped of its political and social context. Instead of being addressed as a systemic issue, it is reframed as an anthropological curiosity or an authentic experience. The images of inequality are consumed in ways similar to how colonial exhibitions once presented difference: as something to be observed, enjoyed, and then left behind.

This process carries risks. The more poverty is aestheticized, the more it risks being normalized as a form of entertainment rather than recognized as a structural problem. Urban segregation deepens, disadvantaged communities lose visibility in public life, and empathy is replaced by spectacle. In effect, poverty becomes part of the consumer economy, but the people who live it remain marginalized.

The growing popularity of ghetto tourism and the cultural mainstreaming of urban poverty raise difficult questions about the future of Türkiye’s most populous cities. On one level, these phenomena reflect global patterns of inequality in which marginalized groups are both excluded and commodified. On another, they point to specific dynamics of Türkiye’s urban development, where migration, informal housing, and rapid transformation have created lasting divides.

International organizations such as UN-Habitat warn that urban poverty is becoming entrenched and global, exacerbated by crises such as climate change, pandemics, wars, and economic shocks. In this context, the transformation of poverty into spectacle is not only ethically troubling but also socially destabilizing. Policies to combat inequality may be implemented, but without a cultural environment that acknowledges poverty as a serious challenge rather than entertainment, these efforts are unlikely to succeed, and the imagery of poverty is likely to be spread.

The consumption of urban poverty in Türkiye through tourism, music, or television should be seen as more than a passing cultural fad or a following patterns of global trends. It is a reflection of deeper structural inequalities which stems from its own structures and cultural shifts that could shape the country’s social fabric for decades to come.