A widely read column argues that the latest wildfire on the Gallipoli Peninsula (Gelibolu) in Canakkale stems from a century of planting fire-prone red pine, rather than from organized arson.

According to Eray Ozer from T24, building on historical botany and wartime records, the piece states that policymakers ignored the area’s natural vegetation and prevailing winds, and that everyday human activity continues to set off fires. As the writer put it: “They did not burn it. We did.”

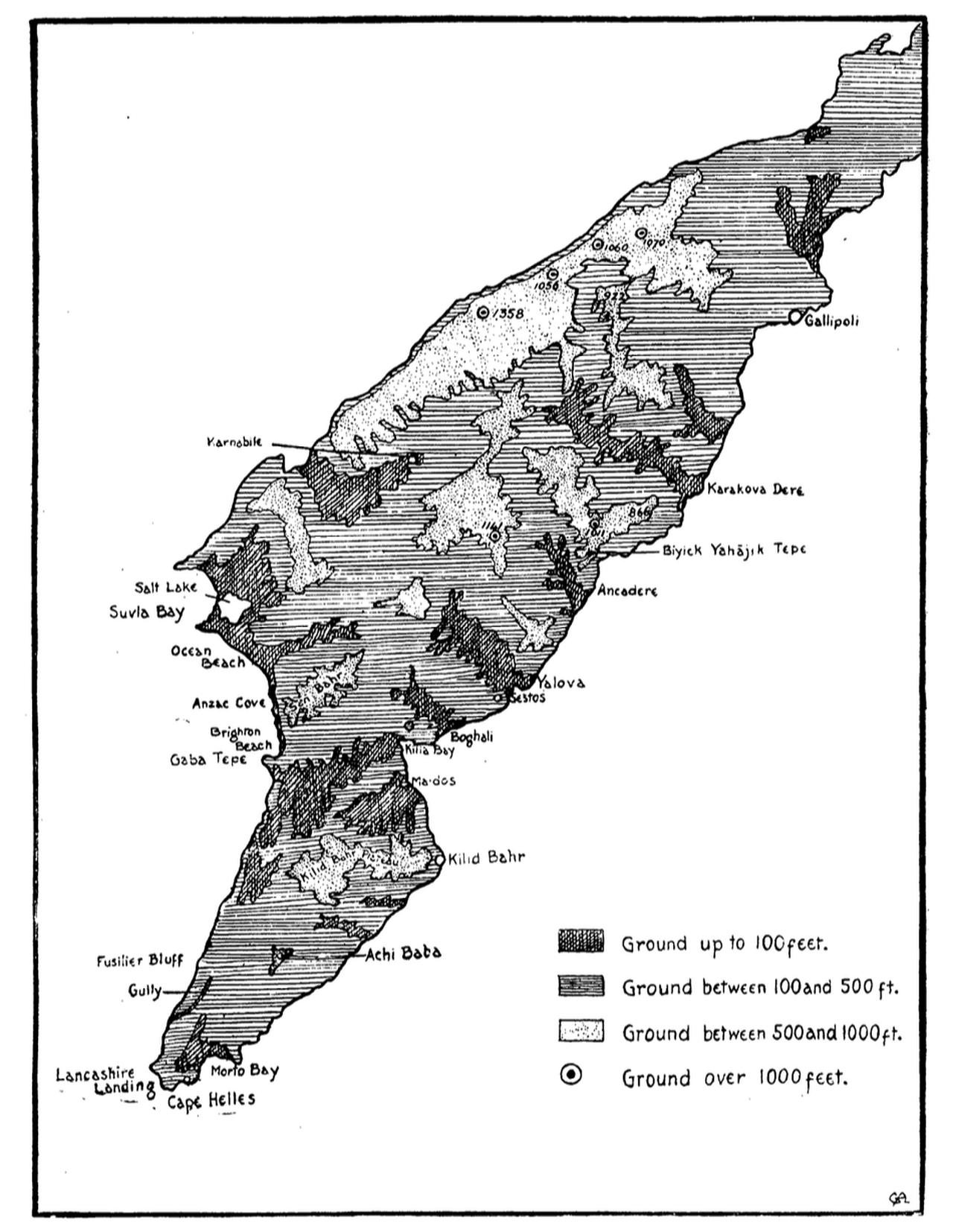

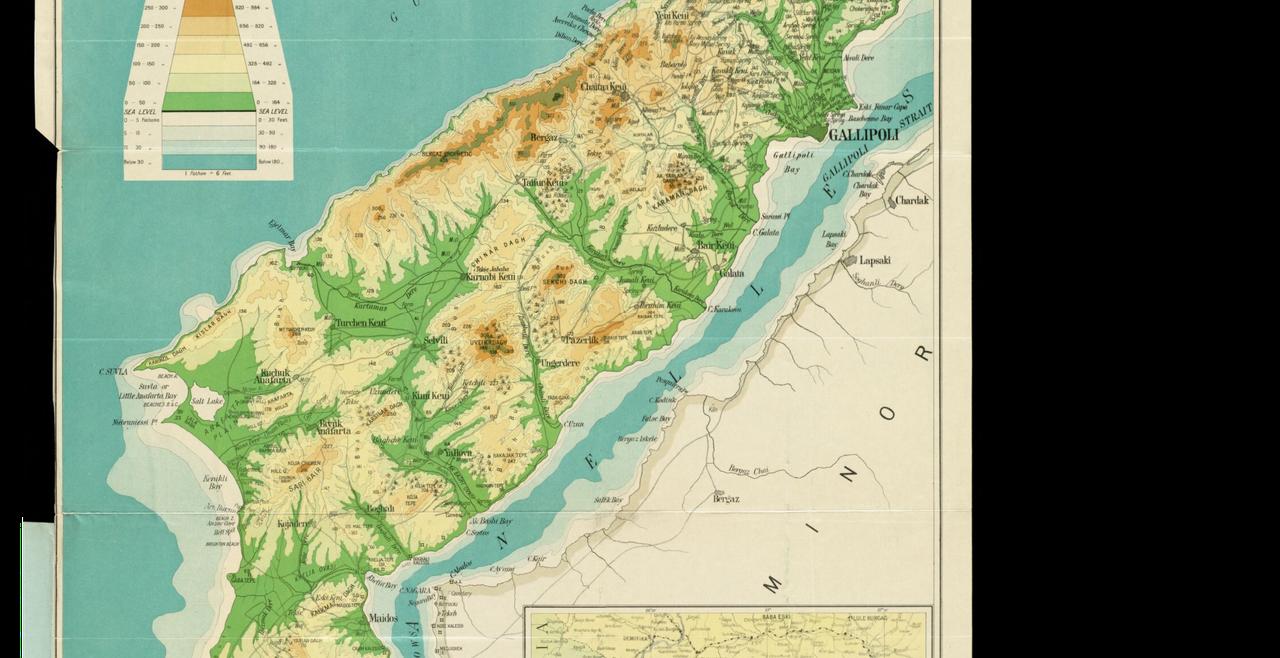

Citing British botanist William Bertram Turrill’s 1924 paper “On the flora of the Gallipoli Peninsula,” the column says the peninsula historically lacked a continuous forest. Turrill reportedly found “no trace of forest,” apart from a small stand of Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis) near Kilitbahir, and noted that trees did not grow above about 150 meters (500 feet). Instead, the terrain was dominated by maquis (Mediterranean scrub), low oaks, and herbaceous plants; of 472 recorded species, 315 were shrubs or herbs.

The writer adds that the higher ground stayed treeless due to scarce water and long-standing use as pasture.

The piece argues that Türkiye has repeatedly replanted Turkish red pine (kizilcam, Pinus brutia) after big fires, even though oak (mese) better fits the peninsula’s ecology.

It points to a 2001 study by Okan Yasar describing oak as the primary native tree and says oak is more fire-resistant and easier to extinguish. The mayor of Eceabat is noted as having objected to replanting red pine after each blaze.

Pushing back against conspiracy claims, the column lists familiar ignition sources: cigarette butts tossed from car windows, stubble burning (the practice of burning crop residues), glass bottles left in the brush, and welding sparks that jump into scrub.

It also underlines how strong northeasterly “poyraz” winds—locally known gusts that can reach around 50 kilometers per hour (km/h)—help fires take off and spread fast.

The writer notes that one recent fire near Sarıcaeli began when a hawk perched on power lines and sparked an ignition. The column argues that the rapid spread of overhead lines across open ground has boxed wildlife into risky contact with electrical infrastructure, which can set off blazes in dry weather.

The analysis also points to 1915 war maps published by The Daily Telegraph, which marked only a small number of trees on the peninsula during the Gallipoli campaign.

Historians Gursel Goncu and the late Sahin Aldogan are cited as long warning that blanket afforestation not only fuels fires but also buries traces of World War I battlefields.

While the piece was being written, smoke reportedly rose again from the burned area. After firefighters seemed to get on top of the blaze in the morning, flames flared up around Ilgardere and Besyol by midday, according to the writer’s on-the-ground account.

Bringing the strands together, the column urges a shift away from planting red pine across the peninsula and toward science-based restoration that matches native cover. It frames the issue as listening to the land’s history rather than chasing culprits, quoting Turrill to stress the baseline: there once was “no trace of forest” to burn on much of Gelibolu.