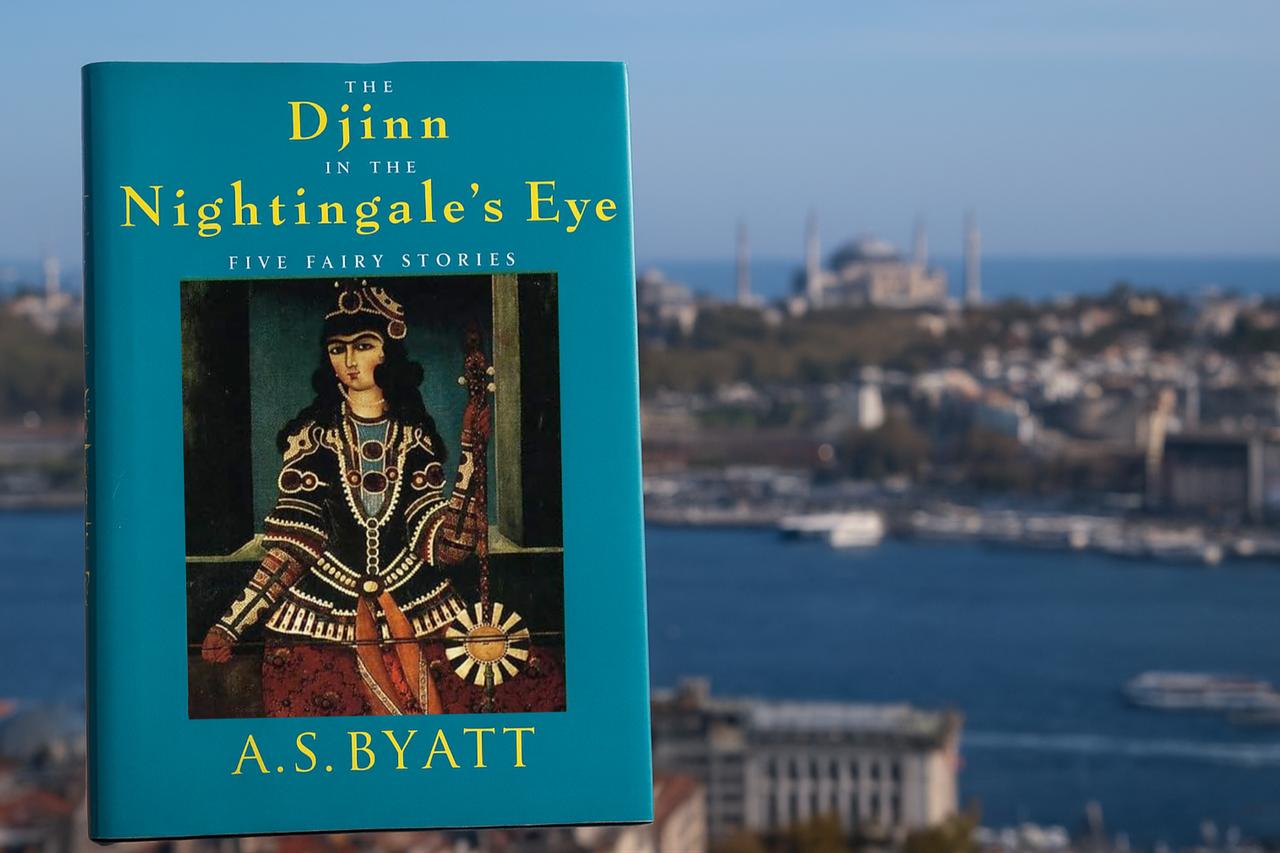

A.S. Byatt’s "The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye" is arguably her most remarkable short story, combining the intellectual play of her novels with the enchantment of myth.

At its center is Gillian Perholt, a narratologist whose professional life revolves around stories. When she travels to Türkiye for a conference, she encounters an ancient bottle in Istanbul and releases a Djinn, setting into motion a tale that revolves around the desire for freedom and the power of narrative.

Unlike most works set in the non-Western world, in Byatt's story, Istanbul is far from an incidental backdrop but functions as the beating heart of the novella. Byatt uses the city as the place where Gillian’s carefully ordered academic life begins to dissolve, allowing wonder, magic, and danger to seep in.

“She could not resist the idea of the journey above the clouds, above the minarets of Istanbul, and the lure of seeing the Golden Horn, the Bosphorus and the shores of Europe and Asia face to face,” Byatt writes, connecting Gillian’s physical arrival to a metaphorical crossing into story-space.

So, let's explore how Booker Prize winner A.S. Byatt’s representation of Türkiye combines enchantment and complexity, a delicate balance for an English author.

Even though her Istanbul is richly layered, intellectually alive, and grounded in real detail, some of her narrative choices echo older Orientalist tropes that turn the city into a site of Western self-discovery.

The tension between Byatt’s conscious literary play and these lingering gazes makes "The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye" both a work of admiration and a text that encourages us to think about how the West writes the East.

As mentioned before, Byatt’s Istanbul is not a one-dimensional Orientalist fantasy but a city brimming with historical and intellectual life. Her descriptions are textured and precise, weaving together the city’s Byzantine, Ottoman, and modern layers.

Furthermore, Gillian Perholt does not choose Türkiye to simply wander through an exotic landscape but attends an academic conference, which she believes “resembles a bazaar, where stories and ideas were exchanged and changed.”

This metaphor signals that Byatt sees Istanbul as a place of active cultural and intellectual production, not a static relic of the past, which has been the fallacy of several Western writers.

One of the most striking features of the novella is the presence of Turkish characters with authentic names, such as Orhan Rifat and Leyla Doruk, who are portrayed as equal participants in the intellectual conversation.

This is a small but significant detail: Byatt resists the temptation to populate her Turkish setting only with nameless “locals” or anonymous vendors. Instead, she places Gillian in a community of colleagues, showing that Türkiye is not just a setting but a site of scholarship. This choice lends realism to the narrative and demonstrates a measure of respect for Turkish intellectual culture.

However, Byatt’s attention to material detail extends beyond conference rooms. She captures the feel of Istanbul’s streets and its storied landmarks, bringing Hagia Sophia, Topkapi Palace, and the city’s minarets vividly to life.

The result is a vision of Istanbul that is busy, layered, and alive; a palimpsest where Gillian’s modern Western perspective intersects with centuries of history. This richness keeps Byatt’s depiction from sliding into a flat, touristic or Orientalist gaze.

Istanbul in Byatt’s novella becomes the threshold through which Gillian moves from the ordinary to the extraordinary. The shift begins subtly, with the heightened sensory experience of the city.

Gillian settles in at the Peri Palas Hotel “across the Golden Horn,” a space that blends modern comfort with local architectural elements, such as tiled fountains, Turkish tiles, airy courtyards.

This creates an atmosphere where the past feels present. The attention to setting prepares both Gillian and the reader for the moment when the real world gives way to the realm of myth.

The pivotal moment comes when Gillian acquires the bottle that contains the Djinn. Byatt describes the Grand Bazaar as “a warren of arcades, of Aladdin’s caves full of lamps and magical carpets, of silver and brass and gold and pottery and tiles,” a description that leans into the fairy-tale tone but also frames the bazaar as a place of possibility.

The purchase of the bottle is not casual; it is ritualistic, signaling Gillian’s crossing into story-space. What was once a conference trip has become an adventure that blurs the line between academic curiosity and personal transformation.

The Grand Bazaar and the atmosphere of Türkiye together create a liminal setting where time and space feel slightly unmoored.

Byatt’s Istanbul becomes a city where a middle-aged Englishwoman can step beyond the constraints of her daily life and into a narrative that allows for magic, desire, and risk.

Even though A.S. Byatt’s Istanbul is richly imagined, her portrayal occasionally risks reducing Türkiye to a backdrop for Western transformation.

The Grand Bazaar scene, for instance, is described in a way that turns the marketplace into a symbolic space rather than a realistic one, more of a narrative threshold than a living part of the city’s economy.

Gillian’s purchase of the bottle feels less like a transaction taking place in a contemporary metropolis and more like an initiation into a mythic tale designed to unfold for her benefit, which reproduces a familiar European fantasy of “finding” the East as a source of mystery and narrative fuel.

Byatt also uses bathing imagery to suggest renewal and transformation. Gillian’s hotel is filled with “tiled fountains, Turkish tiles with pinks and cornflowers in the bathrooms,” which create an atmosphere that merges modern comfort with Ottoman design.

After swimming, Gillian feels physically reawakened: “the nerves unknotted, the heart and lungs settled and pumped, the body was alive and joyful.” This sensory immersion is one of the key steps in her metamorphosis, marking a shift from purely intellectual engagement to embodied experience.

Later, at Topkapi Palace, Gillian looks into the sultan’s bath in the harem, which Byatt describes with archaeological precision. The narrative invites the reader to imagine the women who once inhabited this space, but it also risks turning the harem into a stage for Gillian’s historical imagination, projecting a Western curiosity onto Ottoman domestic life.

These moments are beautifully written, yet they construct a version of Türkiye that primarily serves Gillian’s narrative rather than reflecting its own complexity.

Istanbul’s historic spaces are transformed into thresholds of enchantment, sites that exist to propel the protagonist into a new story.

For some readers, this emphasis can feel less like representation and more like consumption as the city’s architecture and design become instruments of Gillian’s rebirth.

If some scenes risk turning Türkiye into a backdrop for Western transformation, Byatt also builds resistance into the text itself.

One of the most striking examples comes when the Djinn responds to Gillian’s memory of a friend with the observation, “Women have always found ways-.” Gillian immediately interrupts him by saying, “Don’t sound like the Arabian Nights. I am telling you something.”

This interruption reads not only as Gillian’s demand that her story be taken seriously but also as Byatt’s own refusal to let her narrative and even characters slide into the mode of romanticized Eastern storytelling.

This reads like a moment of narrative self-consciousness. Byatt acknowledges that she is working with material deeply associated with European fantasies about the East (bazaars, Djinn, and magical objects, to name a few) but refuses to let those elements take over entirely.

The line becomes a kind of brake, a signal to the reader that the novella is aware of its own position within the tradition of Orientalist storytelling.

Crucially, the Djinn is not a mute figure in this process. He has his own voice and history, and he does not always behave as Gillian expects. Their dialogue is full of push and pull, moments where the Djinn’s stories resist easy interpretation and where Gillian’s responses complicate her role as the Western listener.

Byatt turns their conversation into a meditation on power, interpretation, and cross-cultural storytelling.

So where does this leave us?

Ultimately, Byatt’s "The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye" leaves readers with a sense of Istanbul as both enchanted and mediated, a city of thresholds where magic feels possible but whose primary work is to host a Western protagonist’s transformation.

The novella’s strength lies in its refusal to offer a simple vision: it both revels in Türkiye’s layered history and interrogates its own storytelling choices.

What remains is a text that invites admiration and discomfort at once, asking us to consider not only what we see in Istanbul, but how, and why we choose to tell its stories.