When Venezuelan opposition leader Maria Corina Machado was awarded the 2025 Nobel Peace Prize, it sparked a storm of debate across Latin America and in global media.

The official rationale cited her “efforts toward a peaceful and democratic transition in Venezuela.”

Yet, this simple explanation fails to capture the region’s historical, political, and diplomatic complexities.

Machado’s past maneuvers, her strategic ties with Israel, and emerging documents suggest the prize represents more than a recognition of democratic leadership—it signals alliances with the West.

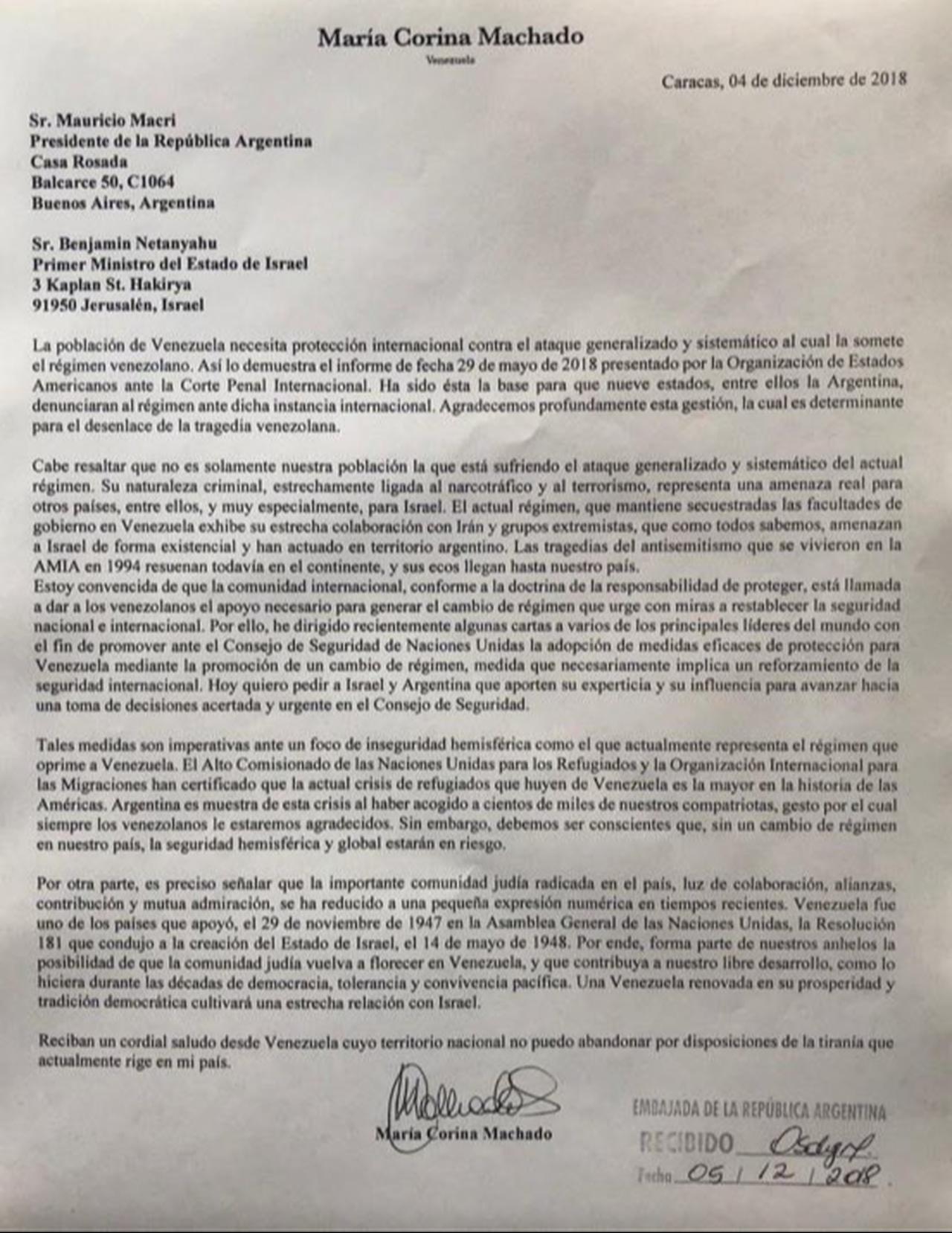

The first key document, dated Dec. 4, 2018, is a letter Machado sent to then-Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

She highlighted the Venezuelan people’s need for international protection against the “widespread and systematic attacks” of the Maduro regime. She argued that regime change should be encouraged, particularly with support from Israel and Argentina.

The letter also alleged collaboration between Maduro’s government, Iran, and extremist groups, framing it as a threat to national and regional security.

The correspondence illustrates Machado’s diplomatic approach and the political message she conveyed to the West: the Nobel Peace Prize acknowledges Venezuela’s democratic struggle while symbolizing strategic Western connections. The letter is documented as an official source, though some claims remain unverified.

The second document is a “Partisan Agreement” signed on July 21, 2020, between Machado’s party, Vente Venezuela, and Israel’s ruling Likud party.

It commits both parties to collaboration across political, ideological, and social domains, emphasizing joint action on geopolitical and security issues.

The agreement seeks to bring Venezuelan and Israeli interests closer together, promoting “freedom, democracy, and market economy” as shared values.

In this context, Machado’s award reads not only as recognition of democratic leadership but also as a tangible symbol of pro-Western strategy.

These documents highlight critical points. Machado’s diplomatic and political initiatives deepen the symbolic weight of the prize. While it can be interpreted as a victory against the Maduro regime, it also serves to bolster international legitimacy and prestige.

Yet they raise a question: is the award an objective “peace prize” or a tool supporting pro-Western political messaging?

The letter to Netanyahu underscores the limits of the award’s practical impact. Framing the Maduro regime as “terrorist and criminal,” Machado requested concrete intervention from the international community.

Latin America’s historical memory of U.S. and Western interventions—in Nicaragua during the 1980s or Chile in 1973—remains vivid, raising questions about the moral and political dimensions of the prize.

The Likud-Vente agreement places Machado’s award within a strategic framework. It suggests the prize is not solely about democratic struggle but also represents a pro-Western alliance. While it may be read as a Maduro-opposing “victory,” it does not guarantee democratic change on the ground; instead, it provides international messaging and diplomatic prestige.

Historical precedents highlight this tension. In 1973, Henry Kissinger received the Nobel Peace Prize while the Vietnam War raged, and civilian suffering continued.

The award symbolized Washington’s diplomatic efforts, yet the human toll persisted.

Similarly, in 1994, Yasser Arafat, Shimon Peres, and Yitzhak Rabin were honored for the Oslo Accords, but the collapse of the peace process revealed the prize’s symbolic nature.

In 2009, Barack Obama received the award early in his presidency despite ongoing military interventions and drone operations in the Middle East, illustrating the gap between intent and action. In 2019, Abiy Ahmed’s temporary peace efforts between Ethiopia and Eritrea were overshadowed by renewed conflict in Tigray.

Earlier examples, such as Carl von Ossietzky in 1939, show that the prize’s applicability and impact have long been debated.

Similarly, Jean-Paul Sartre famously declined the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964, arguing that institutional recognition could compromise intellectual independence.

His refusal underscores a broader lesson: awards, even when prestigious, do not always align with the recipient’s principles or on-the-ground realities, highlighting the complex interplay between recognition, ethics, and influence. Machado’s award fits squarely within this historical pattern: intentions are rewarded, and outcomes remain secondary.

Machado’s political record underscores the award’s controversial dimensions. In 2020, Vente Venezuela signed a “strategic cooperation” agreement with Israel’s Likud party, emphasizing “democracy and security partnership.”

Machado openly supported Israel, even suggesting Venezuela might move its embassy to Jerusalem. This stance drew criticism across Latin America, where public opinion largely favors anti-imperialist and pro-Palestinian positions.

The Palestinian cause is deeply intertwined with historical memory, justice, and anti-imperialist struggle in the region.

Maduro maintains a strong, authoritarian grip on Venezuela. Opposition leaders like Machado contest the legitimacy of elections, challenge media restrictions, and denounce economic mismanagement and hyperinflation.

Her opposition resonates within Venezuela and the broader region, offering both moral support and international visibility, though tangible change remains uncertain.

Here, the causal link is clear: international recognition elevates visibility and legitimacy but does not automatically translate to internal systemic reform, as structural political realities—authoritarian control, economic collapse, and institutional weakness—limit impact.

Awards given during and after the Trump era illustrate how Nobel deliberations can be shaped by political context. Following the Abraham Accords in 2020, discussions about potential recipients highlighted that the prize often recognizes political messaging rather than actual peace on the ground. U.S. domestic politics and Middle East policy can influence committee decisions.

Machado’s award aligns with Trump-era regional policies, projecting a pro-Western profile while reaffirming the historical tension: the prize emphasizes prestige and diplomatic signaling over concrete peace outcomes.

In 2025, Donald Trump brokered a ceasefire in Gaza, ending a two-year conflict, securing the release of 48 Israeli hostages and an exchange involving roughly 2,000 Palestinian prisoners. Plans included the disarmament of Hamas and governance of Gaza by an international transitional authority.

Trump claimed this achievement entitled him to the Nobel Peace Prize, yet the award went to Machado.

The decision underscores how international critiques of Trump’s policies and alliances may influence award deliberations, demonstrating a causal chain where political perception and strategic alliances shape award decisions more than immediate conflict resolution.

Latin America’s political culture remains sensitive to foreign intervention and imperial ambitions. Revolutions in Cuba (1959), Nicaragua (1979), and leftist governments in Bolivia have long tied their struggles to solidarity with the Palestinian cause. Slogans such as “Palestina Libre!” and wall inscriptions reading “No hay paz con ocupación” still appear in Buenos Aires, Santiago, La Paz, and São Paulo.

Machado’s award contrasts sharply with this collective memory: destroyed Palestinian cities on one side, a Nobel Peace Prize on the other.

The causal implication is clear: historical solidarity shapes public perception, generating skepticism toward awards perceived as aligned with Western interests.

The prestige of the Nobel Peace Prize has long been a subject of debate. Machado’s award fits squarely within this historical pattern, serving both as a symbolic triumph and an international political statement. While it offers moral support and visibility to the Venezuelan opposition, it does not ensure meaningful change on the ground.

Latin America’s longstanding solidarity with Palestine helps explain much of the ensuing controversy. The prize rewards intentions, often leaving tangible outcomes in the background; Machado’s ties with Israel and her stance against Maduro raise serious ethical and moral questions.

Ultimately, the gap between prestige and genuine peace invites a global reconsideration of what true peace really means.