When Sipan Hamo, a key SDF figure in their negotiations with Damascus, declared that his forces were “ready to join the new Syrian army, provided our identity and people’s rights are respected,” he framed it as a gesture of reconciliation. To many Western observers, it sounded like progress: a U.S.-backed militia signaling its willingness to fold into a national structure.

But to anyone who has studied the SDF’s history, this announcement reveals something far more complex—and potentially dangerous. Behind the rhetoric of unity and coexistence lies a network of interests, loyalties, and criminal economies tied to one organization that has haunted the region for decades: the PKK terrorist organization.

This is not merely a question of integration. It is a question of sovereignty—and whether the Syrian state can ever be whole while the PKK’s proxy remains entrenched within its borders.

The SDF was born out of war but molded by ideology. When the YPG began expanding across northern Syria in 2013, it did so under the banner of “democratic autonomy.” Yet its command, structure, and doctrine were directly derived from the PKK’s central leadership in Qandil, northern Iraq.

The United States, desperate for an on-the-ground ally against Daesh, chose to overlook that connection. Washington armed and trained the SDF, even as European and American intelligence agencies confirmed that senior SDF commanders maintained constant contact with PKK military councils. The fiction of separation—YPG in Syria, PKK in Türkiye and Iraq—became a convenient diplomatic cover, one that allowed U.S. military support to flow without triggering counterterrorism restrictions.

But inside Syria, the distinction never existed. The PKK’s Marxist-Leninist-inspired governance model was imposed on the population through the PYD, its political wing. Local councils became tools of ideological control, and dissent was punished as “treason.”

Kurdish activists who refused to bow to the PKK line were silenced, imprisoned, driven into exile, or killed.

By 2017, the SDF controlled one-third of Syria—including most of its oil and wheat resources. Instead of building inclusive institutions, it built an economy of extraction and patronage—a shadow state that owed its survival to foreign protection and illicit finance.

Nothing illustrates the PKK’s grip over Syria’s northeast better than its control of the oil fields around Rumelan and Deir el-Zour. After expelling Daesh from these areas, the SDF turned them into a private treasury. Tankers moved daily through smuggling corridors, sometimes across Daesh-held terrain, trading crude for cash and fuel.

According to sources inside the SDF’s own financial administration, figures like Ali Seyr, the PKK’s financial operative in the Jazeera region, directed oil sales and managed revenues through front companies in Lebanon.

From there, profits were wired to accounts in Europe linked to PKK networks. Only a handful of insiders knew the full scope of these transfers, but the scale was enormous—hundreds of tankers leaving Rumelan each day, while local populations remained impoverished.

This wasn’t governance. It was an organized theft.

For a decade, the PKK has weaponized resources meant for Syrians to fund its insurgency across borders. Its oil dealings enriched the same hierarchy that sustains violence in Turkey and Iraq.

Any notion that the SDF represents local self-rule collapses under this reality: it is an armed franchise of a transnational terrorist group, exploiting Syrian territory as a financial and political sanctuary.

To Western diplomats, the SDF presented itself as pluralistic and gender-progressive—a secular, democratic alternative to both Assad’s regime and other rebels. In practice, however, it is ruled by coercion.

Arab tribes in Deir el-Zour were marginalized or purged. Arab youths were forcibly conscripted. Property seizures and arbitrary detentions became routine. Even among Kurds, opposition voices such as members of the Kurdish National Council (KNC) were persecuted.

Schools were forced to teach PKK-style ideological curricula glorifying imprisoned Abdullah Ocalan—the same man who founded a movement responsible for tens of thousands of deaths across the region.

This model created deep resentment. Today, “Rojava” stands not as a beacon of freedom but as a failed experiment sustained by U.S. air power. The rise of anti-Kurdish sentiment—“kurdophobia”—in parts of Syria is not born of ethnic hostility but of exhaustion. Syrians, Arab and Kurdish alike, are weary of living under militias that claim to represent them while serving foreign agendas.

Now, with shifting U.S. policy and the emergence of a new government in Damascus, the SDF faces an existential question: survival or surrender. Hence the talk of “integration.”

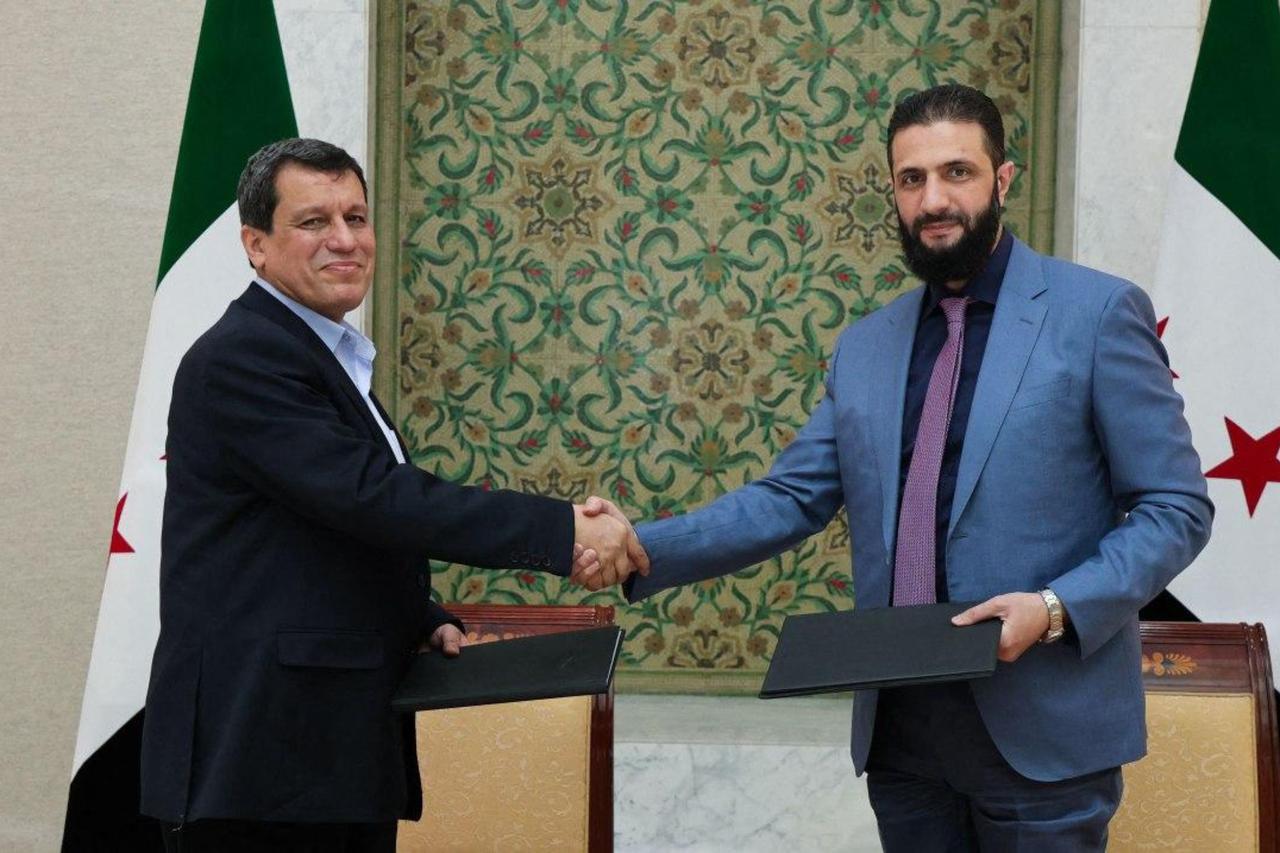

Mazloum Abdi, the SDF’s so-called commander, has already announced a “preliminary agreement” to merge his forces into the Syrian army. But the wording of these proposals is revealing. The SDF insists on joining “as a cohesive bloc” rather than as individuals—effectively demanding institutional recognition as an autonomous army within the state. It also insists on preserving its “identity,” a term so ambiguous it could mean anything from ethnic representation to political autonomy.

This is not reintegration. It is rebranding.

If Damascus accepts these terms, Syria risks legitimizing a parallel military command loyal not to the state, but to the Qandil leadership. Such an outcome would reproduce the very fragmentation that plunged the country into chaos in the first place.

The Syrian army can absorb soldiers, not militias. The PKK cannot be allowed to survive under the camouflage of national unity.

Washington’s policy toward the SDF has been one of moral contradiction. Officially, the United States recognizes the PKK as a terrorist organization. Unofficially, it has spent billions of dollars arming and training its Syrian branch. The justification—defeating Daesh—was pragmatic, but the long-term consequences have been disastrous.

By elevating the SDF, the U.S. created a state-within-a-state that alienated Türkiye, destabilized Iraq, and prolonged Syria’s fragmentation. Even American military officials admit privately that the SDF cannot hold its territory without U.S. troops. As the region recalibrates, the illusion of a sustainable Kurdish-led enclave is collapsing.

Washington’s gradual disengagement leaves the SDF facing a choice: return to the Syrian fold or face irrelevance. The group’s recent statements about joining the “new Syrian army” are less a diplomatic gesture than a survival tactic—an attempt to secure amnesty and institutional protection before the inevitable.

For Damascus, the strategic calculus is delicate. Reclaiming the northeast means regaining access to oil, wheat, and border crossings—vital to national recovery. But integration must not come at the cost of sovereignty.

The Syrian state should pursue a two-tiered approach:

1. Individual integration—absorbing SDF fighters who are Syrian citizens into the national military through retraining and vetting programs, while excluding and prosecuting PKK cadres involved in terrorism or corruption.

2. Political deconstruction—dismantling the PYD’s parallel institutions, replacing them with elected local councils under Syrian law, and restoring state services.

Symbolic gestures, such as offering formal military titles or amnesty to figures like Mazloum Abdi, may be necessary for a smooth transition. But under no circumstance should these figures retain command autonomy or political leverage once integrated.

Anything less than full subordination to the Syrian chain of command would be a fatal compromise.

The SDF’s condition—that its “identity” be respected—is at the heart of the problem. What identity? The SDF is not an ethnic or cultural movement—it is a political-military construct born of war. It's supposed that pluralism masks PKK domination, where non-Kurdish members serve as window dressing to secure Western legitimacy.

In policy terms, “respect for identity” should mean protection for civilians, language rights, and local participation in governance. But for the SDF, it means retaining ideological control. Damascus cannot afford to confuse cultural inclusion with political separatism. A pluralistic Syria is possible only when armed ethnopolitical movements disband, not when they are institutionalized.

The PKK’s entrenchment in Syria also threatens broader regional stability. For Türkiye, any PKK foothold along its border is intolerable. For Iraq, it risks spillover as PKK fighters move between Sinjar and Hassakeh. For the Gulf and Jordan, the continuation of PKK-linked enclaves undermines the prospects for trade and reconstruction.

If Damascus succeeds in reasserting control, it will send a clear message: the era of militias carving out fiefdoms in the name of “federalism” is over. That would not only stabilize Syria but also restore a semblance of balance in a region exhausted by endless proxy wars.

True stability in Syria requires two uncompromising principles:

1. There can be no parallel armies. Every armed group must either integrate under full state authority or disarm.

2. There can be no coexistence with the PKK. Its ideology, structure, and funding networks are incompatible with Syrian sovereignty.

The international community should support Damascus in achieving this—not by turning a blind eye to abuses, but by recognizing that dismantling the PKK’s shadow rule is a prerequisite for any genuine peace process.

The SDF’s signal of “readiness” must therefore be treated not as an act of goodwill but as an opportunity for decisive state restoration.

The SDF’s announcement marks the beginning of the end for Syria’s most powerful non-state army. Whether this end is peaceful or violent will depend on how Damascus and its allies handle the transition.

If integration proceeds on the SDF’s terms, the PKK will simply reappear under a new name—stronger, richer, and legitimized. But if Damascus enforces genuine integration, disbands the PYD’s structures, and reclaims control of the oil fields, Syria can finally begin to heal.

The lesson is clear: there can be no federal Syria built on terrorist foundations. The PKK cannot be reformed through dialogue—it must be dissolved through law, integration, and state authority.

Only then can Syria be free—not partially, not symbolically, but completely.