The article was first published by the Türkiye-based think-tank Istanpol in a longer format.

Europe’s security order is being rapidly redrawn. The combination of Russia’s long-term threat, the erosion of the transatlantic safety net, and the urgency to rearm has pushed the European Union into a new era of defence integration.

The launch of the Security Action for Europe (SAFE), which is worth up to €150 billion in EU-backed loans, marks the first time the EU is using its collective financial power to underwrite military spending.

SAFE aims to help member states procure defence equipment jointly, strengthen Europe’s defence industrial base, and reduce fragmentation. The loans, raised on capital markets and repayable over 45 years, are part of the broader Readiness 2030 initiative, designed to translate higher national defence budgets into genuine collective capacity. The political message is clear: Europe must “spend better and more” to defend itself.

SAFE also represents a decisive step toward defining what European strategic autonomy actually means in terms of industry and finance. Yet, the very rules that make SAFE a credible integration tool, related to strict eligibility and supply-chain requirements, also make it exclusive.

This creates a paradox: as the EU consolidates its internal defense market, it risks deepening the divide with capable non-EU partners, above all Türkiye.

Under current regulations, only EU member states are eligible to receive SAFE loans. Non-EU countries can join common procurements only if they are EEA/EFTA members (Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein), Ukraine, or if they have special bilateral agreements, such as partners with Security and Defence Agreements with the EU, including the UK, Canada, Japan, and South Korea.

Türkiye is absent from all these categories. It is neither an EU member nor an EFTA partner, and despite being a NATO ally, it lacks any formal security or defence partnership with Brussels. Even more decisively, the presence of Greece and Cyprus, both of which are politically opposed to Türkiye’s participation, effectively blocks any attempt to open SAFE to Ankara in the short term.

Beyond these political obstacles, the lack of shared foreign and security policy objectives, as underlined in paragraph 28 of the latest Council statement and confirmed by the European Commission’s report on Türkiye’s low alignment with the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy, further hinders any prospect of structured cooperation.

This exclusion, however, tells only part of the story. As a recently published paper written by Alper Coskun also noted, the interdependence between Europe’s security and that of Türkiye has intensified, not diminished, since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The contradiction is striking: while Europe’s defense integration accelerates, the EU’s most militarily capable NATO ally remains institutionally sidelined.

Türkiye is not part of the EU’s institutional machinery, but it is deeply integrated into Europe’s security and defence ecosystem. Its strategic geography, military capacity, and growing defence industry make it an indispensable actor in the evolving continental order.

Türkiye’s defence industry has undergone a profound transformation over the past decade. Defense exports surpassed $7 billion in 2024 and now reach more than 170 markets, while companies such as Baykar, ASELSAN, Roketsan, and TUSAS co-produce with European partners in aerospace, missile, and naval systems.

This evolution has shifted Türkiye from a dependent buyer of Western systems to a technologically capable actor whose platforms and subsystems increasingly appear in European and NATO procurement chains. Its growing industrial links with Italy, Spain, Germany, Poland and Romania reflect not only greater competitiveness but also a deepening pattern of functional cooperation driven by shared operational needs and complementary capacities.

At the same time, Türkiye remains a frontline NATO ally, with the second-largest standing army in Europe, and serves as a key operational hub for the Alliance’s southern flank. The country’s strategic geography—straddling the Black Sea, Middle East, and Eastern Mediterranean—gives it an outsized role in managing crises that directly affect European security.

As many analysts and experts have noted, Türkiye’s security is closely intertwined with Europe’s—and Europe’s own resilience is diminished when Türkiye is kept at arm’s length. SAFE, therefore, represents not only a financial instrument but also a test of whether the EU can translate this strategic interdependence into coherent policy.

A recent signal of this shifting landscape came in November 2025, when the EU appointed a military advisor to its delegation in Ankara for the first time. Although largely symbolic, the move reflects ongoing discussions in Brussels about the need for a more structured defence dialogue with Türkiye and acknowledges growing pressure, particularly from Germany, to explore deeper cooperation in critical capability areas such as drone technology and defence industrial production.

From an industrial policy perspective, Europe wants to reduce its reliance on the U.S. and other external suppliers. Crucially, however, the regulatory framework itself does not prevent cooperation with Türkiye.

The 35% flexibility for non-EU components is broad enough to accommodate Turkish subsystems, provided that political conditions permit. What ultimately limits Türkiye’s inclusion is not the design of SAFE, but the political environment surrounding it.

Above all, the veto power exercised by Greece and Cyprus, Ankara’s low alignment with EU foreign policy positions, and persistent trust deficits linked to concerns over sanctions compliance and export controls.

In other words, the obstacles to cooperation are primarily political, rather than industrial, even if industrial rules reinforce a preference for inward-looking European solutions.

Türkiye’s exclusion is symptomatic of this tension. It highlights the disconnect between Europe’s pursuit of autonomy and its reliance on non-EU actors for actual military capabilities. Ankara’s ability to mass-produce drones, artillery, and ammunition at scale could make it a valuable partner for European states struggling to replenish their stocks after two years of war in Ukraine. Yet political obstacles, most notably Greek and Cypriot opposition, prevent even limited institutional engagement.

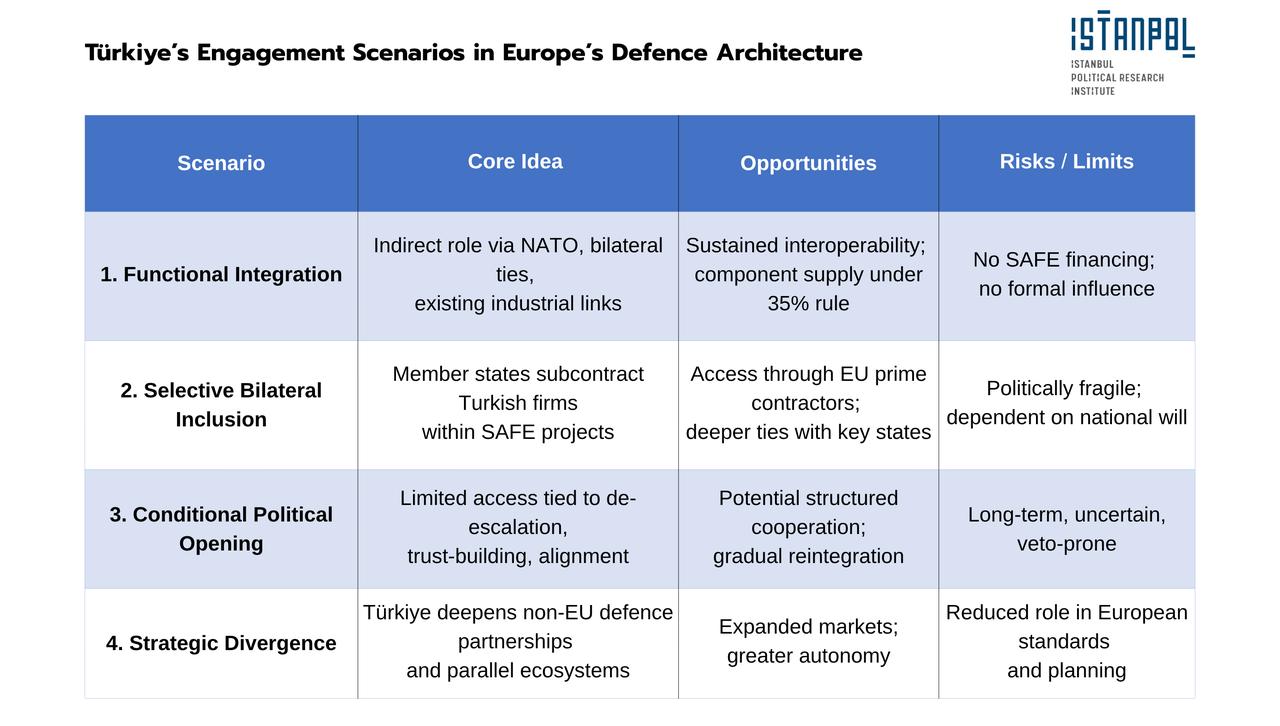

Although Türkiye cannot formally join SAFE, its interaction with the emerging European defence order can evolve along several plausible pathways. These scenarios range from pragmatic adaptation to strategic divergence.

Scenario 1: Functional integration without formal access

The most likely short-term scenario is one of indirect participation through NATO mechanisms and bilateral industrial partnerships.

Türkiye already collaborates with Italy and Spain on aerospace systems, participates in the German-led European Sky Shield Initiative, and engages with Poland, Romania, and Portugal on joint defence ventures. These arrangements allow Türkiye to remain functionally integrated into Europe’s rearmament drive even while excluded from SAFE’s financing.

Within this framework, Turkish firms could continue supplying components under the 35% non-EU content rule, particularly in ammunition, UAV systems, and naval platforms. Such arrangements would preserve interoperability and sustain industrial ties, albeit without access to EU-backed financing or political visibility.

Scenario 2: Bilateral inclusion via selective partnerships

A second, more ambitious path would involve Türkiye’s selective participation through member-state-driven consortia, in which an EU-based company leads a SAFE-funded project while subcontracting to Turkish partners.

This arrangement would depend on the political flexibility within the Council and the practical necessity among member states to achieve rapid production at lower costs. Germany, Italy, or Spain could champion such cooperation, especially if SAFE’s rigid industrial clauses prove counterproductive to meeting urgent defence needs.

This approach mirrors existing pragmatic patterns in migration, energy, and trade: cooperation by necessity rather than consensus. It would also help anchor Türkiye in Europe’s industrial network without triggering institutional confrontations.

Scenario 3: Conditional pathway through political normalisation

A third, medium-term scenario would link any SAFE-related participation to improvements in Türkiye–EU political relations, particularly de-escalation with Greece and Cyprus or renewed dialogue under a renewed EU–Türkiye Statement.

This would not imply renewed accession talks but rather sectoral integration based on mutual interest and conditional trust. Under such a framework, Türkiye could gain partial access to European procurement programs in exchange for progress on regional confidence-building measures and alignment with EU export-control regimes.

However, the timeline for such a scenario extends well beyond the current SAFE application phase and depends on broader political recalibration between Ankara and Brussels.

Scenario 4: Strategic divergence and parallel alignment

The final scenario would see Türkiye doubling down on strategic autonomy through deeper partnerships with Gulf countries, Central Asian states, and post-war Ukraine. In this setting, the EU continues to build its defence capacity inwardly, while Türkiye positions itself as an alternative hub for defence production, cooperating with NATO where useful, but building parallel frameworks where access is denied.

This outcome would consolidate existing trends in Turkish foreign policy: hedging between alliances, maximising flexibility, and expanding export markets beyond Europe. For the EU, it would mean reduced leverage over a capable regional power whose cooperation remains vital to European security.

Regardless of which path prevails, the structural reality remains one of mutual dependence. Europe’s defence-industrial base cannot easily substitute the scale, geographic reach, and operational experience that Türkiye brings to the table. Conversely, Türkiye benefits from maintaining integration with Europe’s technology standards, supply chains, and export markets.

SAFE is therefore not just an EU financing instrument but a strategic mirror: it reflects both sides’ interdependence and mistrust. Europe’s pursuit of strategic autonomy will likely continue alongside NATO structures and flexible, ad hoc coalitions and formats in which Türkiye already plays a role. The challenge is to ensure that institutional exclusion does not evolve into strategic detachment.

Several northern European actors could still help bridge the gap between Türkiye and the EU’s evolving defence ecosystem. Sweden and Finland, which are now both EU and NATO members, bring credibility as consensus-builders within the Union and have traditionally positioned themselves as pragmatic interlocutors with Ankara. Norway, though outside the EU, remains closely integrated into European defence structures through NATO, the EEA, and its participation in several capability projects; it can therefore play a complementary role by reinforcing dialogue in NATO formats where Türkiye is fully present.

For the EU, SAFE’s credibility will rest on its ability to deliver both efficiency and inclusiveness. Restricting cooperation to the single market may strengthen internal autonomy but weaken external partnerships essential for Europe’s broader defence resilience. A mechanism that encourages “European solutions” yet sidelines NATO allies like Türkiye risks deepening fragmentation rather than overcoming it.

For Türkiye, SAFE highlights the cost of political estrangement. Ankara’s defence industry is technologically competitive but strategically isolated. Without access to European financing and standard-setting processes, Turkish firms risk being treated as peripheral suppliers rather than equal partners. Re-engaging with European partners through formal dialogues, especially on export control, IP rights, and industrial standards, could gradually rebuild trust and open pragmatic channels of cooperation.

As the Nov. 30, 2025, deadline for member states to submit their SAFE investment plans approaches, Türkiye’s exclusion appears certain. Yet this should not be seen as an endpoint. SAFE is the first step toward a European defence treasury, and its ripple effects will continue well beyond the initial funding round.

Whether Europe succeeds in building a coherent defence architecture will depend not only on financial means but on its capacity to cooperate across institutional boundaries.

The paradox of SAFE is that it seeks to make Europe more secure while inadvertently leaving out one of NATO’s most pivotal actors.

However, the responsibility does not lie solely with the EU. If Türkiye wants to be taken seriously as a long-term defence partner, not only industrially but politically, it will also need to address the sources of mistrust that limit cooperation.

Greater transparency in defence procurement, clearer firewalls between state power and private industrial actors, and more predictable alignment with EU and NATO foreign policy positions would help reassure member states that cooperation with Ankara would not create vulnerabilities at moments of crisis.

Breaking this cycle of distrust is a prerequisite for transforming existing functional cooperation into a more structured and strategic relationship.

The real question, therefore, is not whether Türkiye can formally join SAFE, but whether Europe can achieve true strategic resilience without Türkiye.

The answer will depend less on legal frameworks and more on political imagination—on whether Europe chooses to define security in terms of its (normative) borders or through its partnerships.