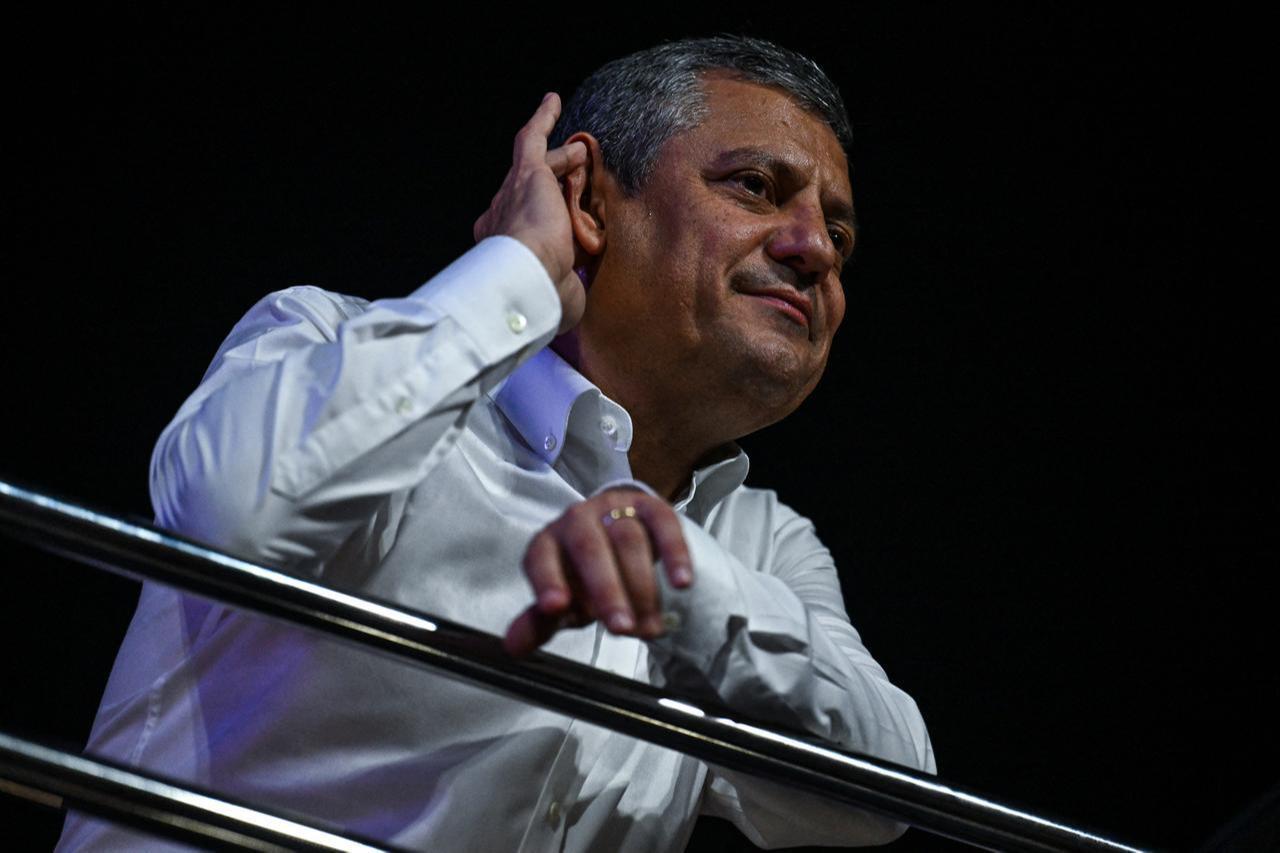

When main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) leader Ozgur Ozel first announced a boycott campaign in March 2025, few expected it to impact Türkiye’s political and commercial landscape.

What began as a protest against media bias soon turned into a wider campaign urging citizens to use their purchasing choices as a form of political expression.

Now, months later, the CHP has revised its boycott list, removing the coffee chain Espressolab after talks with the company and its young customers.

The decision suggested that Ozel’s strategy had real economic effects while also revealing the challenges of using consumer activism in Türkiye’s polarized climate.

CHP leader Ozel’s call for a boycott came amid large demonstrations in Istanbul’s Sarachane Square following the arrest of Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu.

Standing on a platform before a massive crowd, Ozel accused several media outlets of ignoring the protests and siding with the government.

“You will not cover this square but you will earn money from the people who are here. That cannot happen,” he said. “From now on, those who profit from us while serving the palace will be named one by one. Either you will acknowledge us or you will hit rock bottom.”

The campaign targeted what Ozel described as pro-government conglomerates, including companies linked to major media groups. He framed it as a call for neutrality rather than retaliation, saying that those who remained silent would face “the power of consumer choice.”

In one of his speeches, Ozel added, “A million people gathered that night and you did not cover it. Then you invite my editor-in-chief for a coffee. A cup of coffee may be remembered for forty years [Turkish saying], but an act of betrayal will stay in my memory just as long.”

The boycott quickly gained traction online. Hashtags such as #Boykot and #BoykotListesi dominated social media for days. Supporters described the movement as a legitimate response to media censorship, while critics said it blurred the line between political protest and economic coercion.

Although Ozel’s boycott began as a reaction to media coverage, it soon evolved into a larger statement on political accountability.

For many CHP supporters, it became a way to express frustration with institutions they saw as complicit in silencing dissent. Others questioned whether using economic pressure as a political weapon was sustainable or fair.

The campaign deepened Türkiye’s existing polarization, dividing not only political groups but also businesses and consumers. Supporters celebrated what they viewed as a “grassroots movement of consumer justice.”

Opponents, however, warned that such actions risked politicizing everyday life and intensifying social divisions.

Among all the companies mentioned in the campaign, one stood out for its unexpected symbolism: Espressolab.

Founded in 2014 by businessman Esat Kocadag under Kocadag Yatirim, the chain grew from a small campus café to a major brand with more than 300 stores across Türkiye and abroad, including in Germany, Portugal, Egypt, and Qatar.

During his Sarachane speech, Ozel used Espressolab as an example. “I love all kinds of coffee, Turkish or filter, but do not buy it from Espressolab,” he said, accusing the chain of “taking over campuses.”

The mention quickly turned the coffee brand into a political flashpoint.

Espressolab’s image had already become linked with government figures after President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) leader Devlet Bahceli were photographed there in 2020, shortly after attending prayers for the reopening of Hagia Sophia as a mosque.

The viral photo made the brand a symbol of proximity to power, a perception that grew once it appeared in CHP’s boycott campaign.

Part of the Kocadag family conglomerate, which also owns Emirgan Sutis and other hospitality businesses, Espressolab had positioned itself as a domestic rival to global chains such as Starbucks.

Yet in today’s Türkiye, where even lifestyle choices can carry political weight, its rapid growth became entangled in debates about identity, loyalty, and economic justice.

By October 2025, the campaign that began as a symbolic protest had created visible market pressure.

Espressolab’s sales reportedly fell sharply after months of student-led boycotts and social media criticism. Speaking at a rally in Istanbul’s Sisli district this week, Ozel said the company’s revenue had dropped to one-tenth of its previous level.

“When I first mentioned the boycott, it came from the young people,” Ozel told the crowd. “They said a coffee chain entered the campuses, raised prices, and dominated the market. We added it to the list because the students were already boycotting it.”

Ozel said representatives from Espressolab had later reached out to the CHP to request a meeting. “We directed them to our youth branches,” he said. “They told us they had lowered their prices and were ready to make a contribution. They said all profits from university branches would be donated to the March 19 Solidarity Fund to support students and families affected by that period.”

Ozel then announced that the CHP had officially removed Espressolab from its institutional boycott list. “The decision belongs to the youth,” he said. “Let them judge for themselves. Look at the discounts, look at the sincerity. We as the CHP are removing them from the list, but the students will decide whether to continue or not.”

Espressolab was also removed from the official website, which lists the companies subject to CHP’s consumer campaign. The move was seen as both a recognition of the brand’s response and an example of how the boycott had achieved tangible impact through market and social pressure.

The boycott movement quickly drew criticism from the government and ruling party figures, who argued that it encouraged social division and targeted national companies.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, speaking in late March 2025, said, “We will not leave any of our companies to their mercy.” He accused the opposition of attempting to damage Turkish businesses for political gain.

Türkiye's ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) spokesperson Omer Celik described Ozel’s approach as “political bullying,” saying the CHP leader had “boycotted his own merit.” Celik said, “Every time he speaks, he attacks our party, our media, and our companies. This aggressive language will only harm him. The people of Türkiye can see this destructive mindset clearly.”

Critics outside the government also questioned the sustainability of the campaign. Some argued that boycotts risked punishing ordinary workers employed by large corporations rather than their executives or owners.

Others pointed out that such efforts might strengthen the perception of a divided economy, where even consumer behavior reflects political allegiance.

The Espressolab episode illustrates the broader reality of Türkiye’s deep political polarization, where businesses, culture, and everyday choices can become extensions of ideological battles.

Coffee shops, bookstores, and even tourism companies have become informal markers of political identity.

CHP’s partial reversal shows both the reach and the limits of consumer activism. The campaign demonstrated how social media and public opinion can influence corporate behavior, yet it also revealed the difficulty of sustaining boycotts in a highly interconnected economy.

For Ozgur Ozel, the boycott appears to have served its purpose of signaling that the opposition is willing to use new tools to challenge what it sees as unfair structures of media and power.

However, as he himself acknowledged, the final judgment now rests with the consumers who turned a cup of coffee into a measure of political conscience.