Two NATO allies, Croatia and Slovenia, signed a declaration on military cooperation in Zagreb on Sept. 5, pledging tighter military-technical collaboration, deeper coordination between their defense industries, and broader interoperability between their armed forces.

Croatia's Defense Minister Ivan Anusic framed it as a “new chapter,” with Slovenian Defense Minister Borut Sajovic adding that “the world has changed,” a line that signals a response to a harder European security environment since 2022.

The text tracks with a regional template from earlier this year: in March, Albania, Croatia, and Kosovo signed their own declaration to strengthen defense-industrial links, expand joint training, counter hybrid threats, and back Euro-Atlantic integration. That trilateral format stays “open” to others, which hints at a wider, modular security architecture among NATO members and partners ringing Serbia.

“Croatia and Slovenia, as friendly countries and NATO allies, share common interests in peace and stability in our neighborhood, especially in Southeast Europe. We recognize the opportunity to strengthen cooperation and defense industries, which will also contribute to economic growth in both countries,” Anusic said on social platform X.

Sajovic, for his part, told reporters that “the world has changed and this requires further strengthening of cooperation in defense and all other areas.”

He also emphasized that Zagreb and Ljubljana have a “great responsibility” in the Western Balkans, particularly in maintaining peace in Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Serbia, on the other hand, voiced concern over Croatia-Slovenia defense deal, warning that such moves threaten regional stability and exclude neighbors from vital security discussions.

Belgrade reads the deal as a political signal as much as a technical pact. Serbian Foreign Minister Marko Djuric condemned it for “building walls instead of bridges” and undermining trust, a message calibrated for a domestic audience already wary of March’s Albania-Croatia-Kosovo declaration.

“Croatia and Slovenia are sending the message that walls are being built instead of bridges,” Serbian Foreign Minister Marko Djuric said.

"We are in a region that has gone through many things in the last 30 years. Creation of additional alliances without consultations and discussions with neighbouring countries raises many issues and causes concern," Djuric also stated.

Sajovic’s reference to Kosovo resonates sharply in Belgrade because of recent developments. In March 2025, Kosovo, Albania, and Croatia signed a trilateral defense declaration to expand joint training, resilience, and defense-industry links.

Following this, within weeks, Kosovo announced a historic military buildup. “We will allocate €1 billion for our army,” Prime Minister Albin Kurti declared, unveiling a 60% defense budget increase and plans for Black Hawk helicopters, ammunition plants, and drone factories.

Kosovo broke away from Serbia and declared independence in 2008. Led by Türkiye, to date, over 100 countries have recognized Kosovo’s independence. Belgrade has not recognized this move, encouraging the Serbian minority both politically and financially to remain loyal to Serbia. Most of the remaining Serbs in Kosovo live in several northern municipalities, where tensions often flare into violent incidents. To this day NATO-led peacekeeping force KFOR maintains a strong presence in Kosovo.

KFOR still maintains roughly 4,650 troops on the ground, already limiting Serbia’s room for maneuver in Kosovo, especially in Serb-majority municipalities in Kosovo. Adding Slovenia and Croatia’s closer interoperability and industrial synergies raises the specter of quicker, better-prepared responses in the event of unrest, particularly as Kosovo appears to be moving further away from a solution with each passing day.

From Belgrade’s vantage point, the cumulative effect is a shrinking of its coercive leverage in Kosovo.

Meanwhile, Slovenia’s invocation of Bosnia also raised eyebrows in Serbia. Just days after the announcement of the deal in Zagreb, Ljubljana barred Republika Srpska’s (RS) leader, Milorad Dodik, from entering the country, an unusually assertive step by a Balkan state often seen as cautious in regional turmoils. By pairing defense cooperation with “responsibility” for peace in Bosnia, Slovenia signals it is ready to push back against secessionist currents.

For Serbia, which has positioned itself as the secessionist Serb leader's main ally and protector, this looks like a coordinated diplomatic and security squeeze. If Croatia and Slovenia tighten interoperability, they also enhance their ability to shape EU and NATO stances on Bosnia, leaving Belgrade more isolated in defending RS’ status.

The EU angle, however, compounds the pressure. Serbia’s foreign-policy alignment with the EU fell to just 47% in 2024, largely because Belgrade refuses to sanction Russia. Brussels has urged Serbia to make a “strategic choice” between the EU and its partnerships with Russia and China. Croatia and Slovenia, firmly embedded in the EU and now coordinating more closely on defense, are positioned to press Brussels for a harder line on Serbia in both Bosnia and Kosovo.

“Croatia and Slovenia are sending the message that walls are being built instead of bridges … the process could have been more inclusive and transparent," Djuric said, confirming this concern.

In addition to all this, Belgrade’s discomfort is heightened by its reliance on Russia and China as counterweights. Serbia still buys Russian gas and maintains political ties with Moscow, even as it seeks EU funding. Russia remains a veto-holder on Kosovo at the United Nations, giving Serbia diplomatic cover.

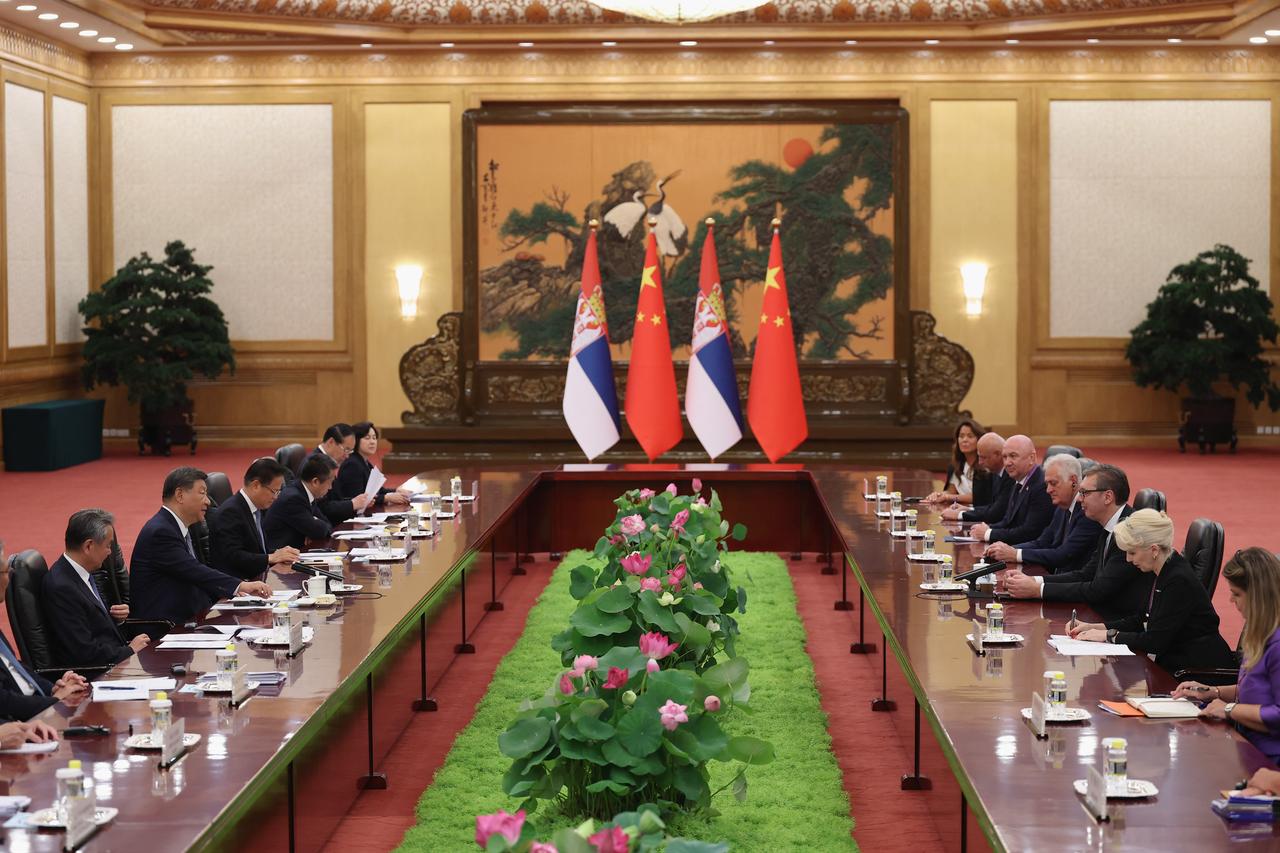

China, meanwhile, has become a crucial military partner. Serbia has already acquired Chinese FK-3/HQ-22 air defense systems and, in July, hosted “Peace Guardian 2025,” the first-ever China–Serbia special forces drill focusing on drones and anti-terror tactics. These moves showcase Belgrade’s hedging: while the EU pushes alignment, Serbia signals that it has alternative security partners.

The more Croatia, Slovenia, Albania, and Kosovo interlock under NATO/EU umbrellas, the more valuable Beijing’s role looks to Belgrade’s leadership, both as leverage against Brussels and as a narrative tool at home.

Speaking of narrative tools at home, Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic mentioned the Zagreb deal, just after a protest in Novi Sad.

“Have you noticed that Zagreb and Ljubljana signed a military agreement on how they will trample over the Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo and Metohija? You think this is a joke? The same way you thought I was joking when I pointed out the agreement between Pristina, Zagreb and Tirana? Now it has been widened to include Ljubljana,” Vucic said.

The fact that the Serbian president, who is grappling with anti-government protests at home, made such a comment immediately afterward suggests Vucic is trying to divert public attention. The Croatian-Slovenian defense agreement serves as a convenient tool for this diversion.

The Croatia–Slovenia pact may be limited in scale, but Serbia interprets it as another link in a chain of mini-alliances—March’s Albania–Croatia–Kosovo declaration, Slovenia’s stance on Dodik, and KFOR’s steady presence—that collectively shrink its maneuvering space. Sajovic’s “responsibility” rhetoric tells Belgrade that its neighbors are no longer merely aligning with NATO but also assuming a regional stewardship role over the very issues, mainly Kosovo and Bosnia, that define Serbia’s strategic posture.

The ultimate impact of the Croatia–Slovenia defense declaration will depend on whether it spawns concrete results. If it does, Belgrade’s fears of a tightening NATO ring around it will feel less like rhetoric and more like hardening reality.