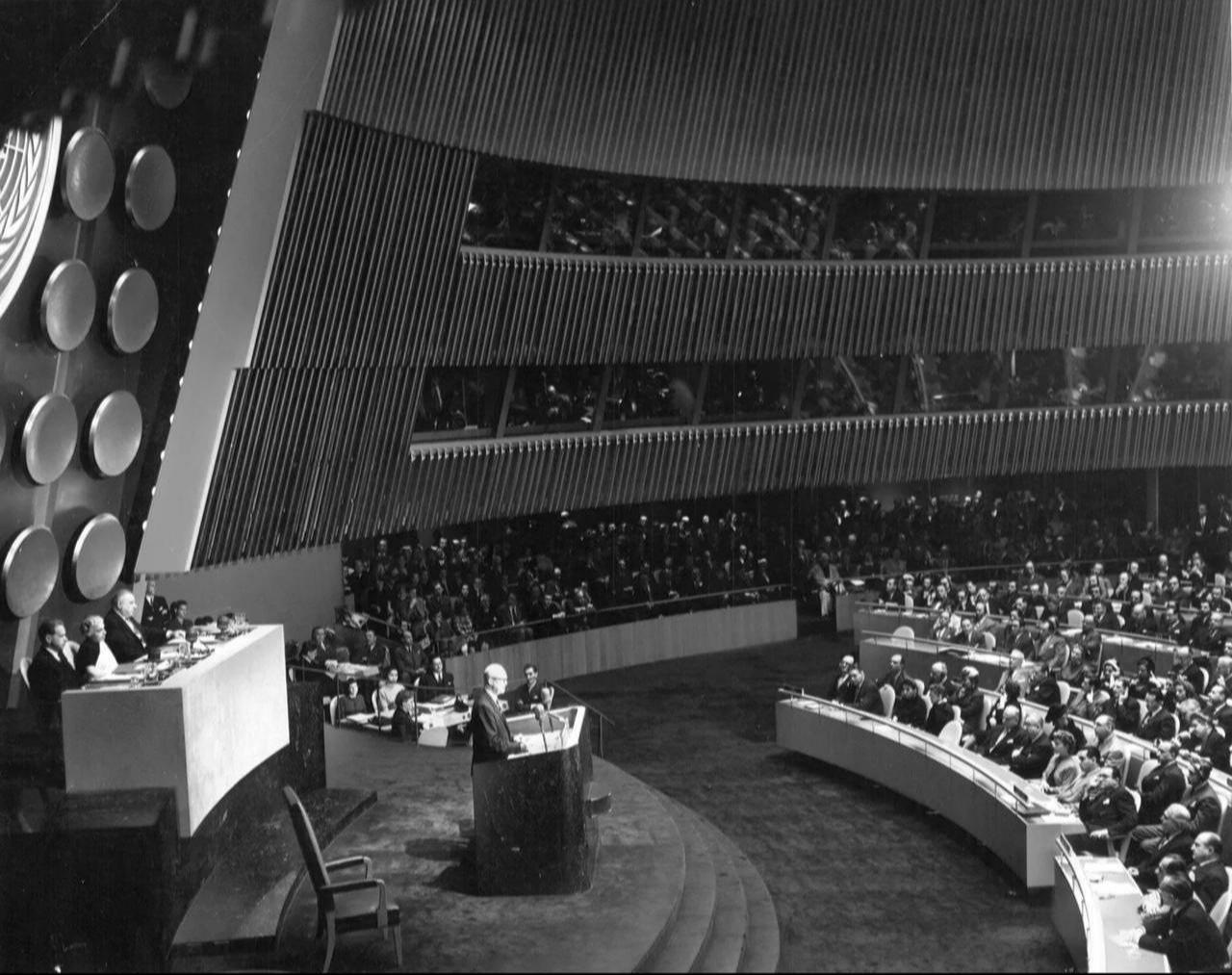

Atoms for Peace, by its very name, evokes visions of harmony and collaboration. Yet when then-U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower addressed the United Nations General Assembly in 1953, Middle Eastern leaders likely raised an eyebrow, skeptical.

"Peace, you say—but who will actually control this atom?" On the surface, it promised scientific progress and energy development, but underneath, it became a vehicle for Cold War diplomacy and strategic positioning.

Nuclear reactors, laboratories, training programs, and technology transfers quietly transformed the Middle East into a testing ground for influence. Each facility symbolized modernization while also serving as a strategic bargaining chip; the more sophisticated the technology, the greater the leverage for those in control.

Even in the mid-1950s, U.S. observers toured Ankara, Cairo, and Tehran, evaluating potential reactor sites, discussing infrastructure, and advising on curricula. In Türkiye, the Cekmece Nuclear Research and Training Center, launched in 1955, became a focal point.

Turkish engineers trained alongside U.S. advisors, mastering technical knowledge while absorbing diplomatic subtleties—how decisions about access to knowledge and resources could shift regional influence.

Students cycled through Oak Ridge and Argonne National Laboratories in the U.S., learning both reactor operation and the nuances of reporting and operational protocol, quietly shaping alliances as much as skills.

In Egypt, the U.S. supported a research reactor at Inshas while closely monitoring former President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s ambitions.

The site selection, construction, and operational planning were intertwined with Washington’s strategic goals: assistance was never neutral. Iran’s Tehran Research Reactor, inaugurated in 1967 with substantial American support, similarly combined prestige with leverage. U.S. engineers spent months on site, ensuring that operations aligned with American interests, demonstrating how technology and diplomacy were inextricably linked.

Israel’s Dimona nuclear facility, constructed in the Negev Desert with French technical assistance and tacit U.S. oversight, rapidly became central to regional security calculations. By the early 1960s, U.S. intelligence assessed Dimona as both a deterrent and a bargaining chip in Arab-Israeli negotiations.

Türkiye and Egypt pursued these programs with dual objectives: modernization and strategic autonomy. Turkish officials negotiated not only for equipment but also access to advanced training during U.S. visits in 1962, 1965, and 1967.

The Cekmece Center, affiliated with Istanbul Technical University, produced engineers capable of independent operation while maintaining subtle alignment with U.S. oversight. Egypt’s Inshas reactor, though modest, served both as a domestic symbol of modernization and as a tool for Washington to maintain strategic leverage over Nasser’s policies.

Diplomacy was embedded at every level. At IAEA conferences in Vienna, Turkish, Egyptian, Iranian, and Israeli delegations debated fuel supply, operational transparency, and reporting mechanisms. Each “technical” discussion carried political weight: control over fissile material, inspection access, and priority in training subtly shifted regional power dynamics. For instance, in 1959, a dispute over shipment schedules to Inshas nearly triggered a diplomatic standoff, quietly mediated by Washington to maintain both technical continuity and leverage.

The chronology of Atoms for Peace in the Middle East reads as a continuous sequence of science and strategy. In 1955, Türkiye established the Cekmece Nuclear Research and Training Center near Istanbul, introducing engineers to reactor operation and the language of scientific diplomacy. Between 1956 and 1960, Washington helped construct Egypt’s first research reactor at Inshas, a collaboration that allowed the U.S. to monitor Nasser’s ambitions while providing a public showcase of national progress.

Türkiye deepened engagement through high-level U.S. visits between 1962 and 1967, ensuring that nuclear capacity advanced alongside modernization goals. In Iran, the U.S.-backed Tehran Research Reactor, inaugurated in 1967, relied on American engineers, controlled fuel shipments, and U.S.-based maintenance training, blending prestige with strategic dependency.

By the early 1960s, Israel’s Dimona facility in the Negev, built with French assistance and tacit U.S. oversight, had become a defining feature of regional power calculations.

The Tuwaitha Nuclear Complex, located 50 kilometers south of Baghdad, had historically hosted three reactors: one destroyed by Israel’s airstrike on June 7, 1981 (Osirak), and two others destroyed during the 1991 Gulf War by U.S. forces. These attacks highlighted the fragility of nuclear infrastructure in conflict zones and underscored how geopolitical tensions could abruptly reshape nuclear trajectories.

From 1957 through the mid-1960s, IAEA meetings in Vienna further intertwined technical discussions with diplomatic negotiations, creating a continuous arc from Cekmeke to Inshas, Tehran to Dimona, where the region’s scientific map became inseparable from its strategic one.

The strategic and scientific foundations laid by Atoms for Peace continue to reverberate across the Middle East. In Türkiye, the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant represents more than an energy project—it is a direct extension of decades-long engagement with nuclear technology and diplomacy. Turkish engineers and policymakers now operate within a framework shaped by historical precedent, balancing energy independence, international regulatory compliance, and regional strategic signaling.

Participation in joint research initiatives and IAEA forums allows Türkiye to assert technical expertise while maintaining nuanced diplomatic leverage, echoing the dual objectives of modernization and strategic autonomy pursued during the 1950s and 1960s.

Iran’s nuclear trajectory also exemplifies the lasting impact of Atoms for Peace. While domestic political ambitions and regional security concerns have transformed the program into a point of international contention, the foundations—training, reactor design, and operational protocols established with U.S. guidance in the 1960s—continue to influence negotiation dynamics.

The 1974 fuel shipment dispute, long past, still serves as a historical lesson: technical dependencies can amplify leverage in diplomatic discussions, shaping both domestic narratives and international bargaining positions. Contemporary rounds of negotiation, sanctions, and inspections cannot be fully understood without reference to this legacy.

Israel’s Dimona facility, though shrouded in public ambiguity, remains central to regional deterrence calculations. Its continued operation and modernization are informed by decades of experience in managing the intersection of technical capacity, diplomatic signaling, and security imperatives.

Across the Middle East, the interplay between scientific expertise and strategic influence persists. Technological assets, training programs, and regulatory frameworks are not merely operational tools; they are instruments of negotiation, prestige, and power projection.

The Tuwaitha site remains a stark reminder of the consequences of conflict: destroyed reactors, interrupted programs, and the need for careful strategic planning in pursuing nuclear modernization. Lessons from the 1981 Osirak strike and the 1991 Gulf War continue to inform policy and energy diplomacy in Iraq and beyond.

Today, the Middle East’s nuclear landscape is inseparable from its diplomatic and strategic context. The principles demonstrated by Atoms for Peace—leveraging technology to consolidate influence, balancing modernization with external oversight, and embedding diplomacy in scientific cooperation—remain active in shaping policy decisions. Modern reactors, fuel cycles, and international collaborations are evaluated not only for efficiency or innovation but also for their capacity to serve broader strategic objectives.

Ultimately, Atoms for Peace established a durable template: scientific advancement and strategic leverage are intertwined. Türkiye, Iran, and Israel continue to navigate this inherited framework, demonstrating how mid-century programs continue to inform 21st-century energy diplomacy, security considerations, and regional power dynamics.

The past and present are connected by the same logic that guided Eisenhower’s initiative: technology, prestige, and influence are mutually reinforcing, and their careful calibration remains central to Middle Eastern politics.

Atoms for Peace must be understood in the Cold War context. The U.S. sought influence over a region of rising tension, countering Soviet overtures. Every technical decision—from reactor siting to fuel shipment—carried strategic significance.

The 1974 fuel shipment dispute with Iran highlighted how technological dependencies could provoke political consequences. Türkiye carefully timed training programs and reactor upgrades to modernize without triggering unrest.

The causal chain is evident: U.S. technology enabled scientific capacity, conferring prestige and leverage, which shaped diplomacy and security.

Contemporary parallels underscore the program’s legacy. Türkiye’s Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant, Iran’s ongoing program, and Israel’s Dimona facility illustrate that these reactors are more than energy infrastructure—they remain instruments of strategic signaling and negotiation.

U.S. sanctions, IAEA inspections, and partnerships with Europe and China overlay historical precedents, showing how Eisenhower’s initiative established decades-long patterns linking science, diplomacy, and strategy.

Eisenhower may have presented a vision of peace with a confident smile, yet the reality was complex. Reactors became symbols of influence, and Atoms for Peace continues as a laboratory shaping visible and invisible dynamics.

The rhetoric of “peaceful purposes” endures, while technical mastery, strategic foresight, and diplomacy silently dictate outcomes. Examining facility construction, training rotations, diplomatic visits, and negotiations reveals a clear logic: technology provision enhanced scientific capacity, amplifying prestige and leverage, which enabled strategic maneuvering. Each stage reinforced the next, shaping both regional politics and technology.

Atoms for Peace was never purely a scientific endeavor. Each reactor, training session, and fuel shipment carried practical and political significance. Scientific capacity and strategic power were inseparable, and contemporary decisions—from Türkiye’s energy diplomacy to Israel’s deterrence strategy and Iran’s negotiations—follow the same logic. Even today, every reactor upgrade, training program, and regulatory negotiation fits into a broader strategic calculus.

In short, Atoms for Peace was a multilayered experiment in diplomacy, strategy, and influence. Reactors tested alliances, capacities, and the balance of power. Eisenhower spoke of peace, but the program’s real legacy is a Middle East where science, strategy, and diplomacy remain permanently intertwined.

Atoms for Peace was never merely a scientific or energy initiative; it was a sophisticated exercise in diplomacy, strategic planning, and influence. From Türkiye's Cekmece center to Egypt’s Inshas reactor, Iran’s Tehran facility, and Israel’s Dimona program, every technical project carried political weight, shaping alliances and regional balances.

The legacy of these mid-century programs is clearly visible today: Türkiye's Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant, Iran’s ongoing nuclear developments, and Israel’s continued operations at Dimona all reflect decades of strategic calculation, diplomatic engagement, and scientific investment.

Modern reactors, training programs, and international collaborations are evaluated not only for their efficiency and innovation but also for their capacity to enhance strategic influence.

In essence, Eisenhower’s vision for peaceful atomic energy created a framework where technology, prestige, and power remain intertwined—a logic that continues to govern Middle Eastern nuclear diplomacy in the 21st century.