The streets of Cairo in the mid-1950s were alive with anticipation. Students debated fervently in university halls, engineers poured over nascent laboratories, and government corridors buzzed with whispered plans. Egypt was at a crossroads. Colonial legacies still shaped its institutions, yet a new vision had begun to emerge: one that sought to elevate the nation as a scientific, industrial, and regional power.

At the center of this vision was Gamal Abdul Nasser, charismatic, determined, and unafraid of audacity. Among his most ambitious projects was the pursuit of nuclear technology—a path that would intertwine Egypt’s destiny with the global powers of the Cold War.

The urgency was immediate. Israel, Egypt’s neighbor and long-standing adversary, was quietly advancing a nuclear program. The Arab world still bore the scars of the 1948 war, with lost territory and humiliation fueling a sense of existential insecurity.

Nasser understood that nuclear energy could serve multiple purposes: as a demonstration of modernity, a strategic deterrent, and a statement that Egypt could rival the great powers in technological sophistication. He saw atomic research not only as science but as diplomacy, ideology, and power rolled into one.

For assistance, Nasser turned to the Soviet Union. Nikita Khrushchev, acutely aware of the strategic stakes in the Middle East, recognized an opportunity. By offering technical support to Cairo, Moscow could expand its influence without triggering direct confrontation with the United States.

Soviet advisors, engineers, and equipment began arriving by the mid-1950s, creating a covert yet tightly monitored partnership. Publicly, Khrushchev lauded Nasser as a visionary, a leader boldly challenging Western imperialism. Privately, however, Soviet strategists harbored doubts about Egypt’s ability to operationalize a nuclear program. Political instability, limited infrastructure, and the sheer technical difficulty of building reactors meant that the project was as symbolic as it was scientific.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, a young Henry Kissinger, then an emerging scholar and analyst at Harvard, was mapping the shifting contours of Middle Eastern power. He recognized that nuclear ambitions, if unchecked, could destabilize the region and provoke a broader conflict. U.S. intelligence services began monitoring Cairo’s program closely.

Washington’s strategy was clear: encourage modernization to strengthen Egypt’s alignment with global norms, while restraining militarization that could spark a regional arms race. The delicate balance between diplomacy, deterrence, and engagement defined early American policy toward Nasser’s nuclear pursuits.

Egypt’s first tangible forays into nuclear research began in 1955 with the establishment of research reactors and scientific centers under Soviet guidance. Nasser envisioned Cairo as a hub where Arab scientists could gather, collaborate, and eventually rival Western nuclear expertise.

The Arab world watched with cautious pride. Yet constraints quickly emerged. Technical expertise was scarce, funding inconsistent, and political turbulence—especially following the 1967 Six-Day War, in which Egypt suffered devastating defeat at the hands of Israel—shifted priorities from ambitious scientific dreams to immediate military and economic recovery.

Egypt’s signing of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1968 marked a pivotal inflection point in its nuclear trajectory. While Nasser’s earlier ambitions had envisioned nuclear technology as both a symbol of sovereignty and a potential deterrent, the NPT framework imposed new international obligations and constraints.

Egypt accepted the treaty as part of its broader diplomatic strategy; to project itself as a responsible actor and to advocate for a Middle East free of nuclear weapons.

Yet, the decision was also pragmatic: by aligning with the emerging global non-proliferation order, Cairo sought continued access to peaceful nuclear assistance under Article IV of the treaty, while simultaneously pressing for Israel’s nuclear transparency.

This dual approach, embracing non-proliferation norms while challenging regional nuclear asymmetry, became a hallmark of Egypt’s policy for decades, influencing its diplomatic posture in the U.N. and the IAEA and reinforcing its identity as both a modernizing and justice-seeking state.

Within this evolving framework, Nasser’s commitment to building scientific and institutional capacity gained new significance, as Egypt sought to reconcile international restraint with national ambition.

Following Nasser’s death in 1970, Anwar Sadat assumed power, inheriting the dual challenges of economic recovery and geopolitical repositioning. Sadat’s approach marked a strategic pivot. By the late 1970s, he embraced the Camp David Accords with Israel, normalizing relations and securing U.S. support for his regime.

Nuclear ambitions were reframed: energy initiatives replaced potential weapons programs, and strict civilian oversight, often monitored by U.S. advisors, constrained military applications. This period illustrates a broader cause-and-effect logic: Egyptian leaders could pursue modernization, but only within parameters set by geopolitical realities and the imperatives of Cold War diplomacy.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, Egypt’s nuclear activity persisted quietly. Scientific institutions in Cairo and the Suez region trained engineers and physicists, and research laboratories continued to operate under civilian pretenses.

These programs, though modest, maintained the intellectual and technical foundation laid during Nasser’s era. Regional rivalries—especially Israel’s continued ambiguity regarding its own nuclear capacity—ensured that the nuclear question remained a latent strategic concern.

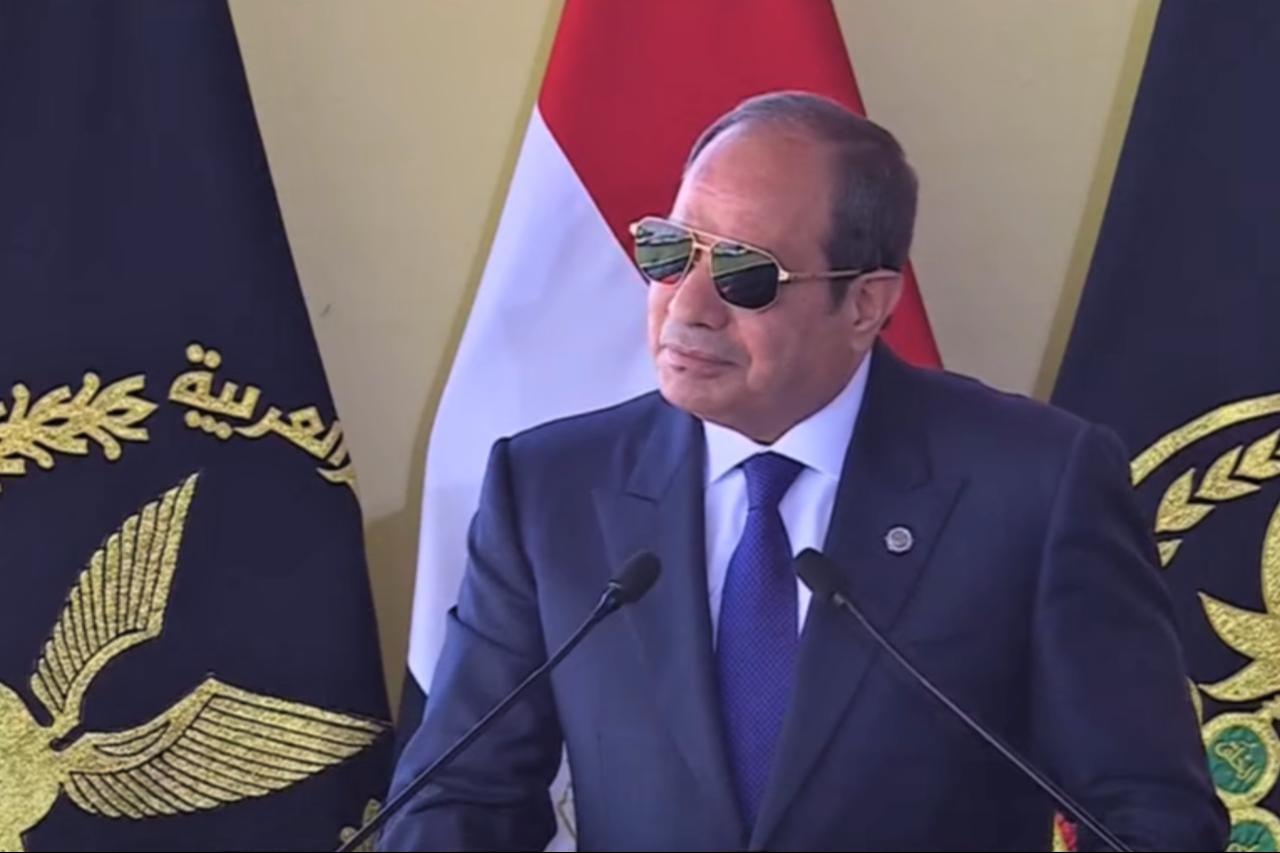

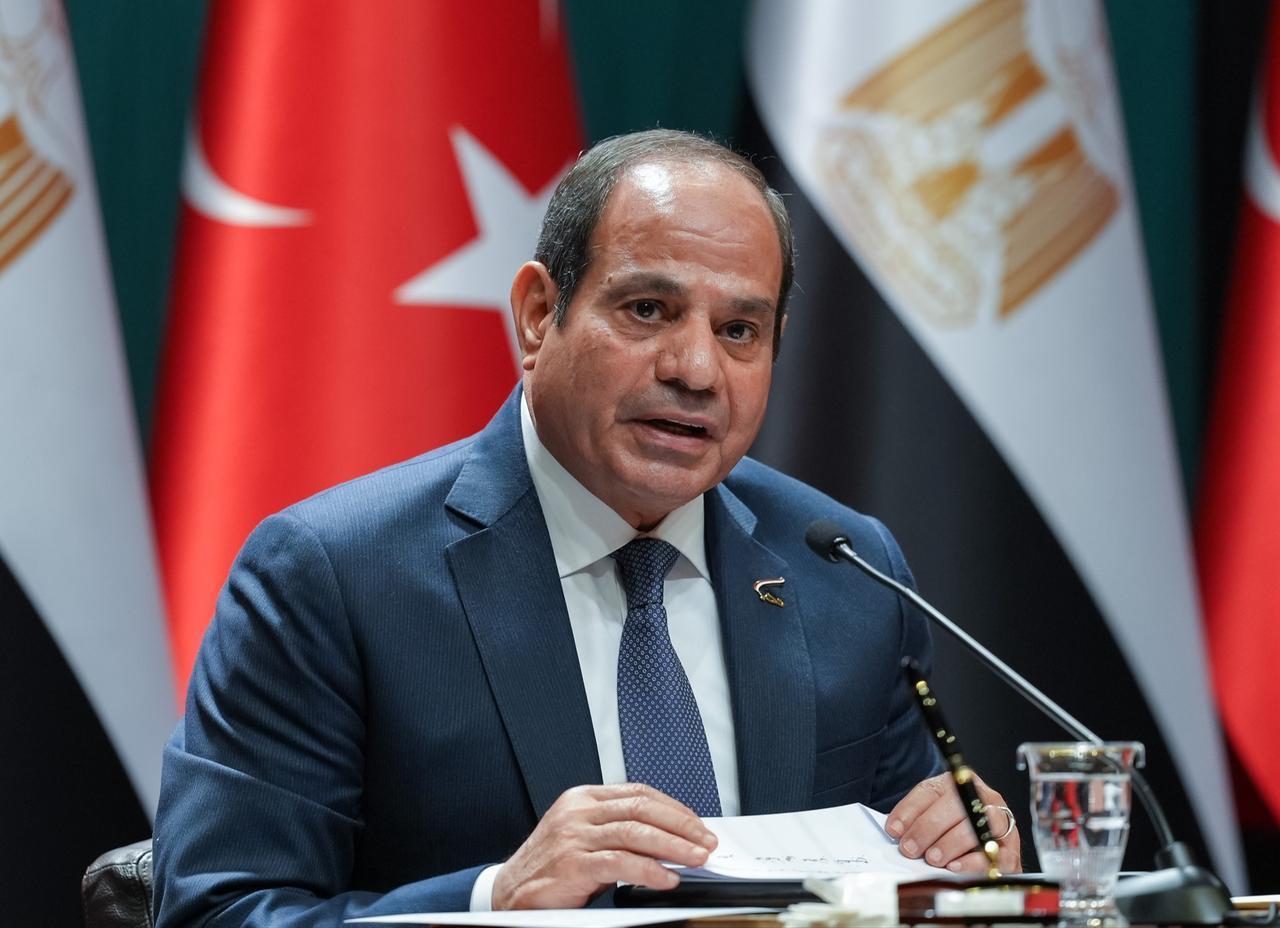

The 21st century saw renewed momentum under Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who rose to power following the 2013 military coup that ousted Egypt’s first democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi. Sisi’s consolidation of power enabled decisive action on long-stalled initiatives.

The Dabaa Nuclear Power Plant project, developed with Russia, aims to construct four VVER-1200 reactors, with the first unit slated for 2026. This program reflects both continuity with Nasser’s original vision and responsiveness to Egypt’s pressing energy demands.

Nuclear development is framed as a symbol of modernization, a domestic political accomplishment, and a tool of regional influence, even as international observers closely monitor technical and financial feasibility.

Sisi’s ascent, like Nasser’s, illustrates the interplay between leadership, institutional authority, and national ambition. The 2013 coup concentrated power in the military and executive branches, creating conditions under which ambitious projects could proceed swiftly, but also raising questions about accountability, civil oversight, and long-term sustainability.

Nuclear infrastructure, therefore, is not merely a scientific endeavor; it is intertwined with the political architecture of the state, the concentration of authority, and the use of technology as a signal of strategic credibility.

Egypt’s regional diplomacy complements its nuclear ambitions. At the October 2025 Gaza Summit, Cairo sought to project moral and political authority, while regional media narratives occasionally hailed Sisi as a “world leader.” Yet this portrayal glosses over the structural and institutional realities underpinning his leadership.

Unlike Nasser, whose vision was backed by widespread political mobilization and nationalistic legitimacy, Sisi’s authority stems primarily from a military-backed coup and centralized executive control. Critics argue that this concentration of power, while enabling swift decision-making on projects like Dabaa, lacks the broader domestic and regional institutional support necessary to substantiate the lofty ‘world leader’ narrative.

The media’s celebratory framing contrasts sharply with the nuanced reality: influence and ambition alone do not confer global leadership without legitimacy, capacity, and enduring political infrastructure.

Egypt’s role in regional nuclear dynamics extends beyond its bilateral rivalry with Israel. While Cairo does not possess nuclear weapons, its civilian nuclear program and diplomatic engagement position it as a stabilizing force, or at least a balancing actor, within the broader Middle East.

For decades, Egypt has advocated for a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in the region, often framing its program as both a tool of energy independence and a bulwark against unilateral nuclear proliferation.

Egypt also observes developments in Iran closely. While Cairo and Tehran have never collaborated on weapons programs, their historical estrangement since 1979 has given way to cautious diplomatic engagement in recent years, particularly in forums addressing Iran’s nuclear activities.

Egypt’s involvement in these discussions underscores its attempt to shape regional norms and mitigate escalation, highlighting its role as both observer and moderator in Middle Eastern nuclear politics.

The history of Egypt’s nuclear ambitions is defined by a recurring tension: the interplay between aspiration and constraint. Nasser’s bold vision, Khrushchev’s strategic caution, and Kissinger’s balancing act converged to create a path characterized as much by limitation as by opportunity.

Sadat’s strategic recalibration postponed operational military potential, embedding Egypt’s nuclear activity firmly within civilian energy frameworks. Sisi’s contemporary initiatives attempt to reconcile symbolic national power with practical technological and economic objectives, demonstrating that nuclear policy is as much about perception and influence as it is about reactors and fissile material.

Arab public opinion, Israel’s opaque deterrence, and the strategic interests of the U.S. and Russia have continuously shaped the trajectory of Egypt’s atomic aspirations. Each leader—Nasser, Sadat, Sisi—operated within constraints imposed by global powers while attempting to assert national agency.

The oscillation between ambition and limitation underscores a central lesson: technology and geopolitics are inseparable, and nuclear energy serves as both a tool and a symbol in the contest for regional authority.

Today, Egypt stands at the intersection of history, technology, and diplomacy. Its nuclear dream is partially realized: infrastructure is slowly materializing, scientific expertise is expanding, and strategic influence is cautiously projected.

From Nasser’s audacious vision to Sisi’s modern nuclear program, the trajectory reveals the intricate entanglement of scientific ambition, political authority, and international diplomacy. The story is not merely about reactors or fissile material; it is a narrative of national identity, enduring aspiration, and the persistent desire of a nation to assert itself amid shifting global currents.

The recent collapse of the JCPOA adds a new layer of uncertainty to this landscape. As Iran’s nuclear activities expand outside the constraints of the agreement, regional states are once again recalibrating their strategic outlooks.

For Egypt, the Iranian case serves as both a warning and a point of engagement. The unraveling of the JCPOA situates Egypt’s nuclear path within a wider Middle Eastern dynamic, one defined not by proliferation itself, but by the shifting boundaries of power, trust, and deterrence.

From Nasser’s audacious vision to Sisi’s cautious engagement with the NPT, Egypt’s nuclear trajectory reflects the shifting boundaries between ambition, restraint, and global order.

*Elif Erginyavuz contributed to this report