When Iraq signed its nuclear cooperation agreement with France in 1976, it was widely perceived as a step toward modernization in the Middle East. However, this move must be understood within a broader historical context. Iraq's nuclear ambitions did not emerge in the mid-1970s; they were part of a longer trajectory of scientific and technological development that began in the 1960s. Under the Baath Party, Iraq sought to consolidate national prestige and strategic autonomy, leveraging oil revenues to fund research institutions and recruit foreign expertise.

By the 1980s, the reactor at Osirak—officially named "Tammuz 1"—had become the most politically charged symbol of scientific aspiration in the Arab world. Behind the rhetoric of "peaceful nuclear energy," a complex network of diplomacy, commerce, and covert calculation unfolded, linking Paris, Bonn, Baghdad, and beyond, while shadowed by parallel nuclear developments in Iran under the Pahlavi regime, Egypt, and Türkiye's Atoms for Peace program.

"Science for development," Iraq insisted; "Technology for influence," responded its European partners. Between 1976 and 1981, contracts, shipments, and training programs quietly transformed Iraq's nuclear landscape into a theater of international power, operating within the shadow of the Cold War, regional conflicts, and global energy politics.

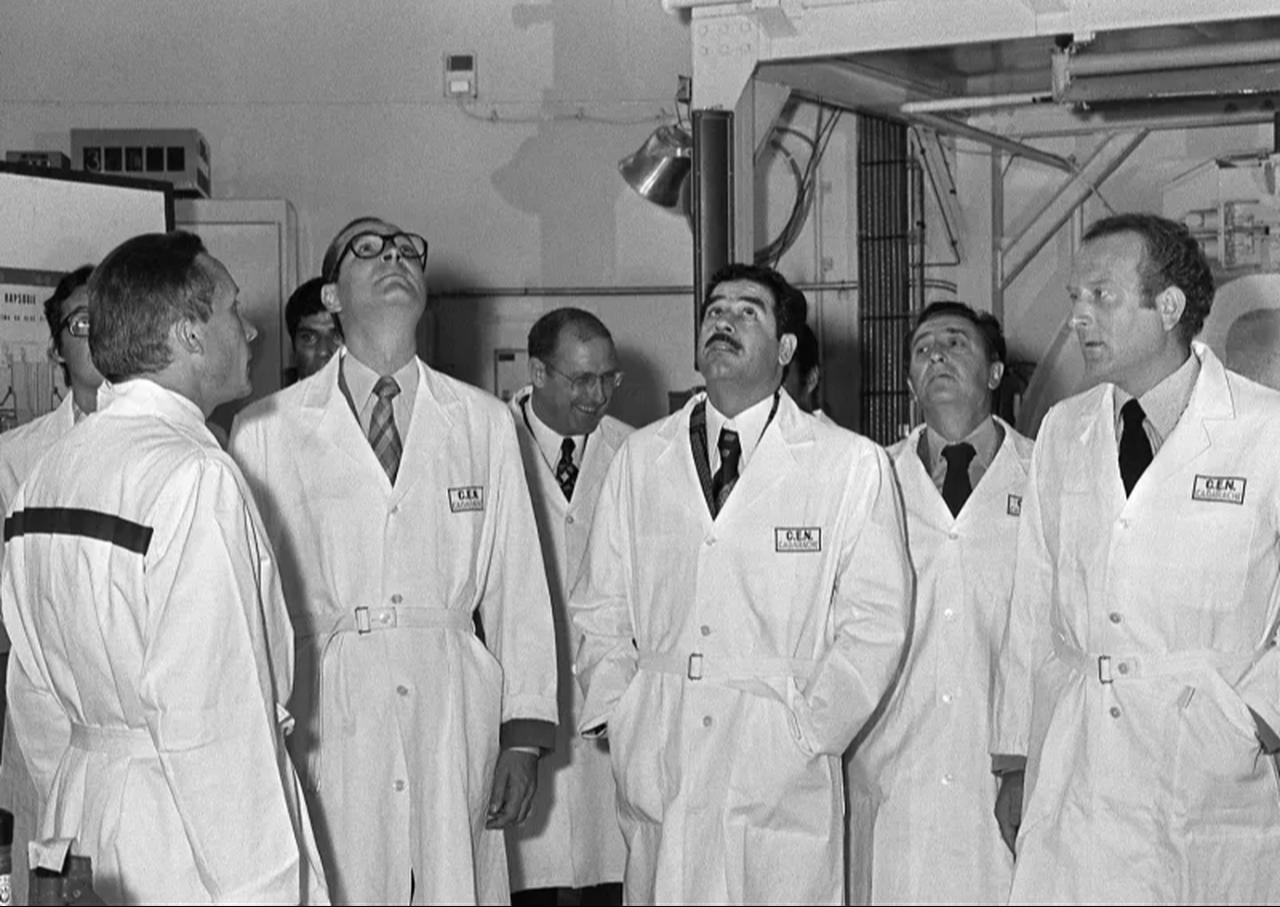

In 1976, France's Commissariat à l'Énergie Atomique (CEA) signed a landmark agreement with Iraq, including a research reactor, two subcritical assemblies, and extensive training for Iraqi scientists. The Osirak reactor, based on the French Osiris model, arrived with high-enriched uranium fuel—drawing concern in Washington, Tel Aviv, and even Moscow.

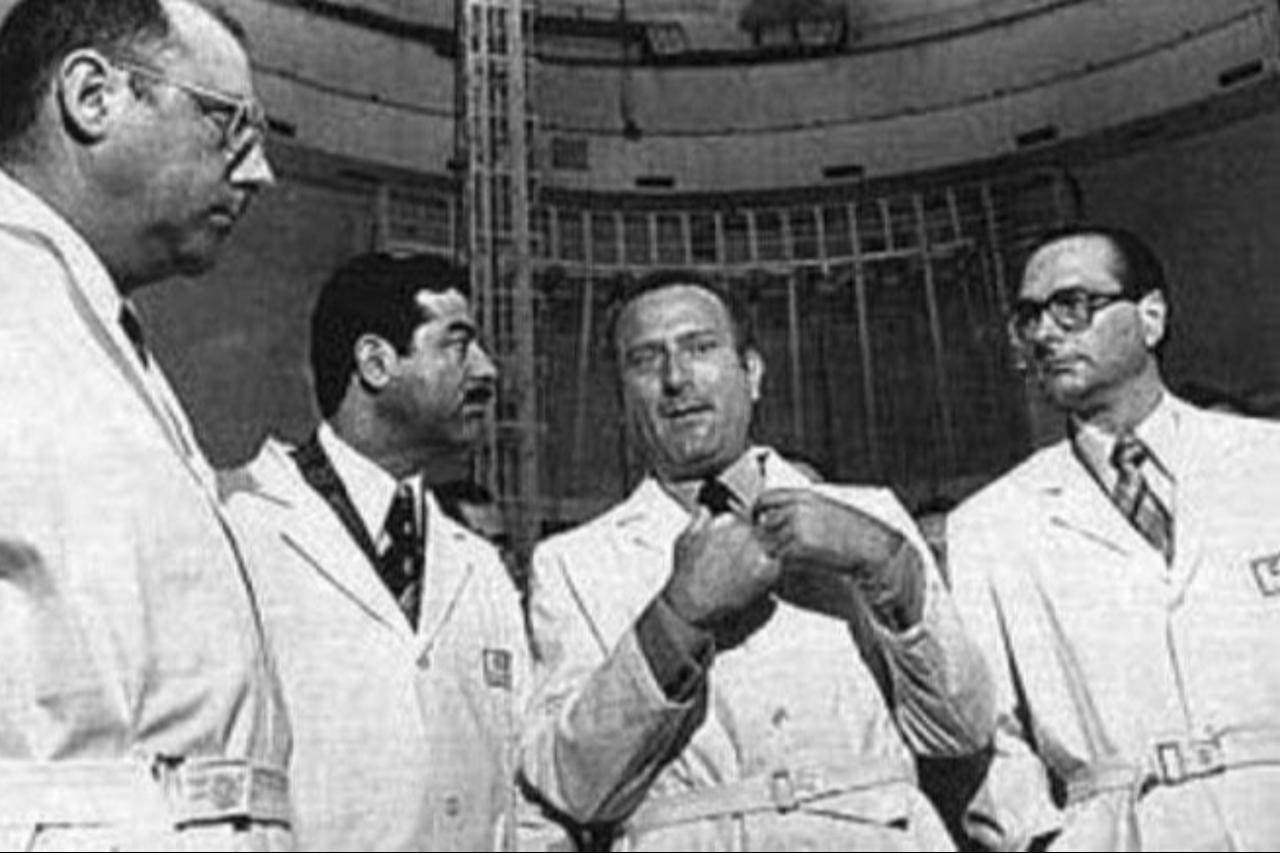

French engineers and Iraqi physicists collaborated closely at the Tuwaitha Nuclear Center near Baghdad. For Paris, it was a commercial success and a diplomatic bridge to the Arab world, consolidating influence after the oil shocks of the 1970s and amid decolonization efforts across North Africa and the Middle East. For Baghdad, it was a path toward self-reliance—a potential deterrent in a volatile region, given Iraq's rivalry with Iran and historical tensions with Israel.

Each shipment and training session involved French oversight, while inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) were promised "full access." In practice, oversight was partial. French technicians noted structural modifications inconsistent with purely civilian research, and U.S. satellite imagery suggested deeper ambitions. By July 1980, U.S. Ambassador Sam Lewis had warned Secretary of State Edmund Muskie and President Carter that Israel might launch preemptive strikes against the reactor—a warning not fully acted upon by the Reagan administration. Soviet and Chinese intelligence closely monitored the developments, assessing regional implications, though without direct intervention.

By 1980, the Iran–Iraq War had transformed scientific cooperation into a security risk. The Osirak reactor had become a diplomatic time bomb. Israeli intelligence, concerned about Iraq’s nuclear potential and French-Italian support, warned that the reactor could soon produce weapons-grade material. The United States, publicly committed to nonproliferation, quietly supported Israeli strategic assessments, reflecting a broader Cold War calculus in which regional nuclear developments were unacceptable to Washington and its allies.

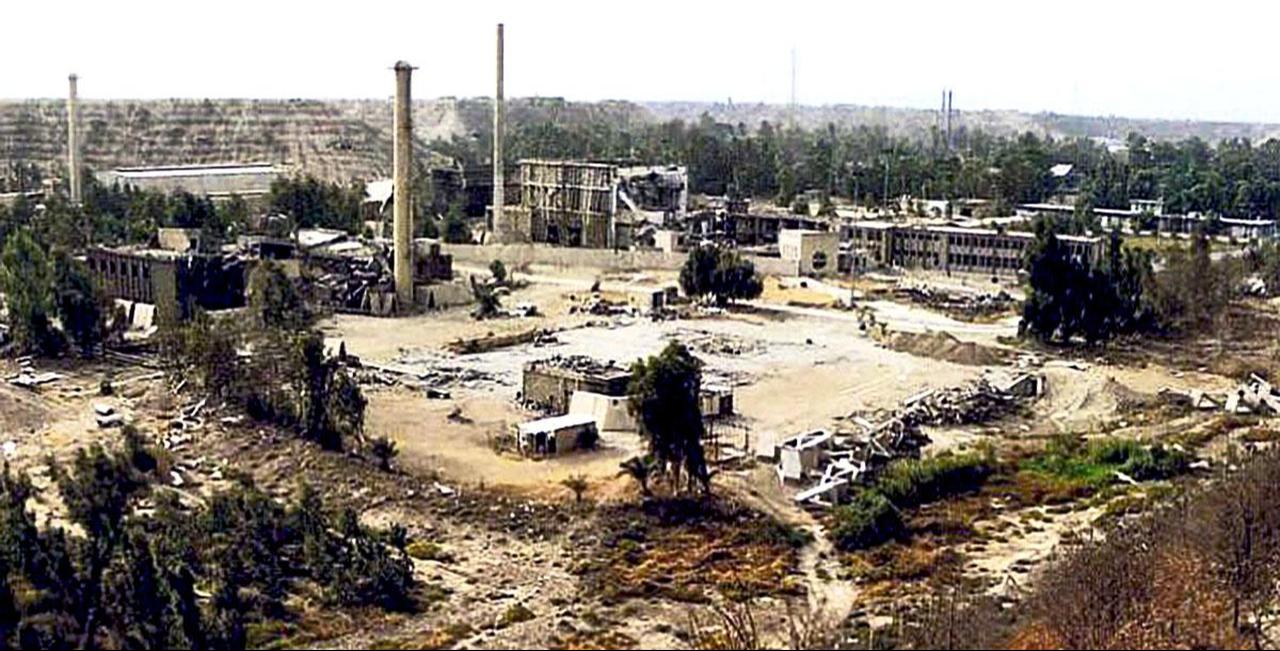

Israel had already acted covertly before the 1981 strike, sabotaging equipment intended for the facility in 1979 and assassinating a leading scientist in 1980. Prime Minister Menachem Begin reportedly timed the attack to pressure Syria and appeal to Israeli voters ahead of elections. On June 7, 1981, eight Israeli F-16s carried out Operation Opera, striking the Osirak complex and reducing years of Franco–Iraqi cooperation to rubble. Ten Iraqi soldiers and one French engineer were killed. The United Nations and the IAEA condemned the attack and suspended technical assistance to Israel, calling for Iraq to be compensated.

France publicly protested but quietly reviewed its export policies, reinforcing inspections and adding new clauses to nuclear cooperation agreements. Baghdad vowed to rebuild, but the ongoing Iran–Iraq War limited European technical support. While the attack may have delayed Iraq’s nuclear ambitions, many experts argue it pushed Baghdad’s efforts underground, accelerating a clandestine weapons program.

While France built Iraq's reactor, West Germany supplied the invisible infrastructure—laboratories, industrial components, and chemical expertise. Firms such as limited liability companies (LLC) and Karl Kolb exported laboratory equipment and dual-use technologies under commercial cover, often skirting export control ambiguities. Intelligence reports from the late 1980s indicated German technicians contributed not only to civilian nuclear projects but also to chemical and metallurgical facilities, forming the backbone of Iraq's broader latent weapons infrastructure.

The Federal Republic of Germany's official stance emphasized "peaceful cooperation" within the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), but enforcement was inconsistent. The duality of Bonn's foreign policy—balancing moral responsibility with economic opportunity—illustrates a recurring tension in Western engagement with Middle Eastern nuclear programs. For Iraq, these ties were indispensable. While France provided visibility and legitimacy, West Germany delivered technical precision and industrial reliability, embedding the country into a web of international dependencies that mirrored, to some extent, earlier U.S. Atoms for Peace operations in Türkiye, Egypt, and Iran.

The 1991 Gulf War exposed the full extent of Iraq's nuclear ambitions. Coalition airstrikes targeted the Tuwaitha complex, revealing remnants of equipment and documentation from both French and German suppliers. U.N. inspections following the war—particularly under the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM)—documented extensive foreign involvement. The discovery validated long-held suspicions that Iraq's civilian nuclear program masked latent weapons potential. Iraq's prior engagements with Soviet and Chinese technical advisors, though limited, also surfaced in UNSCOM records, highlighting the global dimensions of Baghdad's ambitions.

The 1980s nuclear cooperation between Iraq, France, and West Germany offers a critical case study in the intersection of science, commerce, and strategy. Each actor pursued distinct yet interwoven goals that reflected their broader geopolitical ambitions. France sought influence and industrial contracts in a post-colonial Middle East, using nuclear cooperation to expand its technological reach and diplomatic footprint. West Germany, still grappling with its historical legacy, balanced moral responsibility with commercial interest, framing its participation as part of a peaceful, civilian-oriented scientific collaboration. Iraq, under Saddam Hussein, viewed the partnership as a pathway to modernization, national prestige, and a latent form of deterrence capable of shifting regional power balances.

The convergence of these ambitions created an inherently unstable equilibrium—scientific advancement shadowed by strategic mistrust. While the reactors and laboratories symbolized progress, they also embodied competing visions of security and autonomy. The collaboration between Baghdad, Paris, and Bonn demonstrated how technological exchange could serve as both a bridge for diplomacy and a catalyst for suspicion. Meanwhile, Iran, Türkiye, and Egypt pursued parallel tracks, shaping a regional dynamic in which multiple middle powers engaged with nuclear science as a tool of diplomacy, modernization, and influence.

The Iraq–France–Germany nuclear ties of the 1980s were more than a footnote in proliferation history—they revealed how closely science and politics can be linked. Every shipment, license, and training program carried real diplomatic implications. The story of Osirak shows that nuclear technology today isn’t just about energy or research; it’s a tool of power, influence, and international leverage.

The lesson for the 21st century is clear: prestige without transparency invites risk. Covert programs, hidden networks, and regional rivalries make it obvious that nuclear ambitions are inseparable from diplomacy, trade, and strategic planning.