As Taliban authorities swept to power and tightened their grip on Afghanistan, they pushed for the country's water sovereignty, something that Afghanistan had wielded limited control over in the four preceding decades of war.

Five major river basins flow across Afghanistan's borders into downstream neighboring nations. Since the war against U.S.-led forces ended in 2021, the Taliban has been launching infrastructure projects to harness precious resources in the arid territory.

Floods, droughts and other climate change-driven environmental hazards, meanwhile, have become the main cause of displacement in the country, according to the U.N.'s International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Dams and canals have sparked tensions with neighboring states, testing the Taliban authorities' efforts to build strong regional ties, as they remain largely isolated on the global stage since their 2021 takeover.

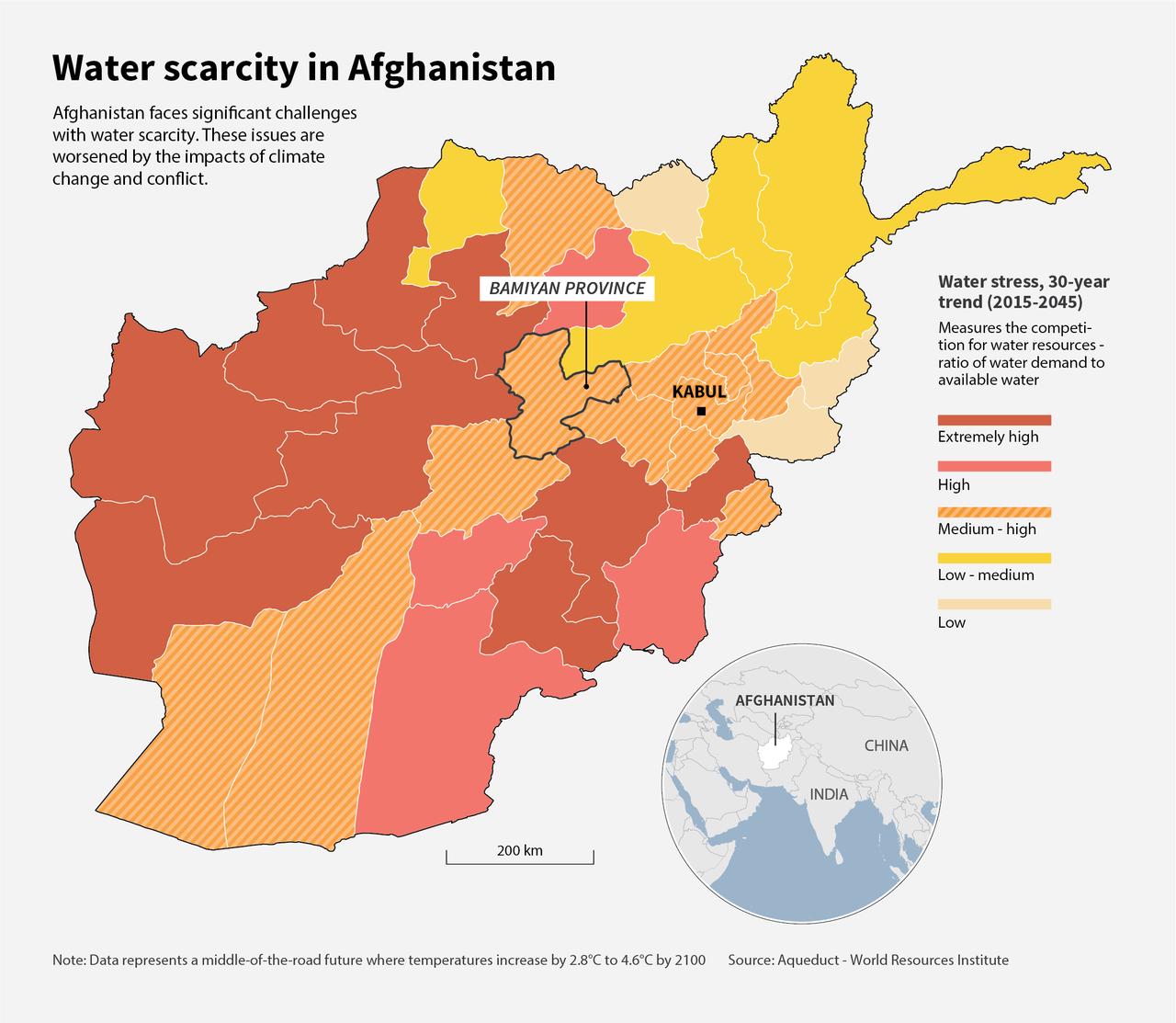

At the same time, the region is facing the shared impacts of climate change, intensifying water scarcity as temperatures rise and precipitation patterns shift, threatening glaciers and snowpack that feed the country's rivers.

Afghanistan is emerging as a new player in often fraught negotiations on the use of the Amu Darya, one of two key rivers crucial for crops in water-stressed Central Asia, where water sharing relies on fragile accords since Soviet times.

Central Asian states have expressed concern over the Qosh Tepa mega canal project that could divert up to 21% of the Amu Darya's total flow to irrigate 560,000 hectares of land across Afghanistan's arid north, and further deplete the Aral Sea.

Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are likely to face the biggest impact, both joined by Kazakhstan in voicing alarm, even as they deepen diplomatic ties with the Taliban authorities, officially recognized so far by only Russia.

"No matter how friendly the tone is now," water governance expert Mohd Faizee warned, saying that "at some point there will be consequences for Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan when the canal starts operating."

Taliban officials have denied that the project will have a major impact on the Amu Darya's water levels and pledged it will improve food security in a country heavily dependent on climate-vulnerable agriculture and facing one of the world's worst humanitarian crises.

"There is an abundance of water, especially when the Amu Darya floods and glacial meltwater flows into it in the warmer months,” said project manager Sayed Zabihullah Miri during a visit to the canal works in Faryab province, where diggers carved into a drought-ridden plain dotted with camels and locusts.

Iran is the only country with which Afghanistan has a formal water-sharing treaty, agreed upon in 1973 over the Helmand River, which traverses Taliban heartland territory; however, the accord was never fully implemented.

Longstanding tensions over the river's resources have spiked over dams in southern Afghanistan, particularly in periods of drought, which are likely to increase as climate shocks hit the region's water cycle.

Iran, facing pressure in its parched southeastern region, has repeatedly demanded that Afghanistan respect its rights, charging that upstream dams restrict the Helmand's flow into a border lake.

The Taliban authorities insist there is not enough water to release more to Iran, blaming the impact of climate pressures on the whole region.

They also argue that long-term poor water management has meant Afghanistan has not gotten its full share, according to an Afghanistan Analysts Network report by water resources management expert Assem Mayar.

Iran and Afghanistan have no formal agreement over their shared river basin, the Harirud, which also flows into Turkmenistan and is often combined into a single basin with the Morghab River.

While infrastructure exists on the Afghan portions of the basin, some has not been fully utilized, Faizee said.

But that could change, he added, as the end of conflict in Afghanistan means infrastructure works don't incur vast security costs on top of construction budgets, lifting a barrier to development of projects such as the Pashdan dam inaugurated in August on the Harirud.

Water resources have not topped the agenda in consistently fraught relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Afghanistan's Kabul River basin, which encompasses tributaries to the greater Indus basin and feeds the capital and largest city, is shared with Pakistan.

The countries, however, have no formal cooperation mechanism.

With the Afghan capital wracked by a severe water crisis, the Taliban authorities have sought to revitalize old projects and start new ones to tackle the problem, risking fresh tensions with Pakistan.

But the lack of funds and technical capacity means the Taliban authorities' large water infrastructure projects across the country could take many years to come to fruition—time that could be good for diplomacy, but bad for ordinary Afghans.