The Syrian Civil War’s aftermath has left the Kurdish northeast in a hazardous limbo, where the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its affiliates continue to obstruct genuine Kurdish representation.

This policy brief argues that the international community’s reliance on the PYD/SDF is strategically flawed, empowering an authoritarian entity rooted in PKK ideology and alienating key regional stakeholders.

As former Assad opposition figures—now occupying pivotal positions in Damascus under interim President Ahmed al-Sharaa—seek to stabilize Syria, the moment demands a reassessment of Kurdish engagement.

Elevating the Kurdish National Council (ENKS) as the primary interlocutor offers a viable path toward federal accommodation, diluting Türkiye’s justification for cross-border incursions and undermining the PYD’s monopoly on force.

Failure to adjust course risks perpetuating violence, fracturing fragile alliances, and forfeiting a critical window for negotiating Kurdish rights within a unified Syrian state.

Background: From uprising to fragmentation

When protests erupted against Bashar al-Assad’s regime in 2011, Kurds watched uneasily, wary that repression in Damascus would spill over into their own communities in Hasakah and Qamishli.

The Kurdish National Council (ENKS), founded in October 2011, aligned with the broader Syrian opposition and Iraq’s Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), championing federalism through negotiation.

The ENKS envisioned a decentralized Syria where Kurdish rights could flourish under constitutional guarantees, not by carving out an independent state.

In contrast, the Democratic Union Party (PYD) had long since adopted Abdullah Ocalan’s doctrine of democratic confederalism, merging grassroots governance rhetoric with the coercive apparatus of the PKK.

As Assad’s forces retreated from Kurdish-majority areas in 2012, the PYD filled the vacuum by seizing control of towns such as Amuda, Derik, Kobani, and Afrin.

What began as a power grab quickly evolved into an iron-fisted regimen: political opponents disappeared, ENKS offices were shuttered, and local councils became extensions of PYD authority.

By 2015, the PYD expanded its military front under the guise of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), exploiting American support against Daesh to entrench its rule.

Despite documenting widespread human rights abuses, international actors treated the SDF as the sole “credible” Kurdish partner.

Meanwhile, the ENKS languished in exile, its members vilified as “Turkish proxies” or “KDP stooges.”

Türkiye's 2019 Operation Peace Spring, launched under the pretext of rooting out PKK influence, underscored the consequences of ceding Kurdish authority to a group indistinguishable from the PKK.

Yet, rather than pivot, the U.S. and the Barzani-led KDP pressed for “unity talks” between the ENKS and PYD, forcing the ENKS into a subordinate role and rewarding PYD duplicity.

Those talks collapsed when PYD-linked militias firebombed ENKS offices in December 2020, even as SDF leadership publicly promised accountability. The message was unmistakable: under PYD terms, Kurdish “unity” is nothing more than acquiescence to a hegemonic patron.

The period from 2021 to 2024 saw the PYD rig local AANES elections, excluding all ENKS participation, and deepen human rights violations, most notably the torture and death of Kurdish opposition politician Amin Aisa al-Ali in SDF custody.

As the PYD oscillated between alliances with Washington, Moscow, and Assad, it demonstrated that its priority remained regime survival, not Kurdish welfare.

In December 2024, when Assad’s regime finally collapsed, those who once led the revolution—figures like Ahmed al-Sharaa—returned to Damascus to head a transitional government.

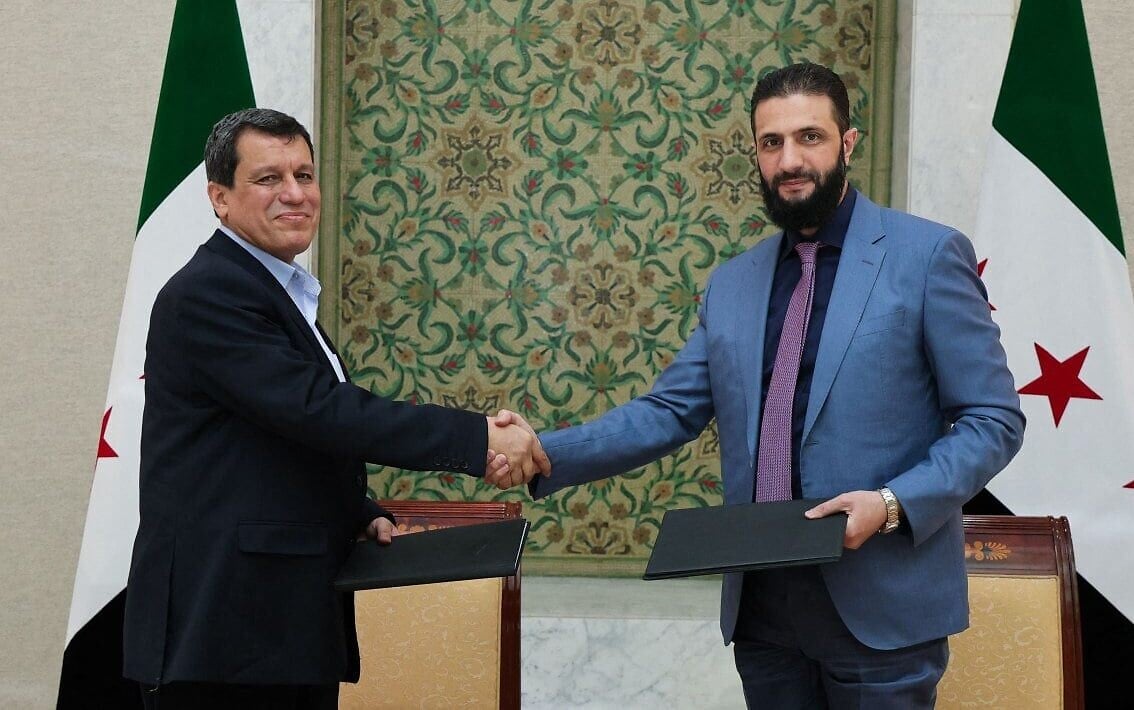

They reached a landmark agreement with the SDF in March 2025, integrating northeastern territories into the Syrian state and validating Kurdish citizenship rights.

However, because the ENKS had been marginalized for years, the PYD feigned participation in dialogue while rejecting meaningful decentralization, ensuring that any promise of Kurdish inclusion remained hollow.

Analysis: PYD’s authoritarian impediment, regional fallout

The PYD’s insistence on monopolizing Kurdish representation has subverted opportunities for a coherent federal settlement. Internally, its governance model has blurred the line between administration and coercion.

Local councils operate under PYD oversight, not popular mandate.

Asayish checkpoints patrol Kurdish towns with little accountability, undermining the rule of law and eroding community trust. Independent journalists, civil society activists, and ENKS-aligned politicians have faced arbitrary detention, “disappearance,” and torture on charges of “spying for Türkiye” or “undermining the revolution.”

The PYD’s record of forced displacement—particularly of Arab and Turkmen villagers near Manbij and Tell Abyad—has further fractured intercommunal relations, undercutting claims of inclusive governance.

When thousands of displaced Arab families returned to retake their homes from PYD security forces, Turkish-backed militias stepped in, citing the PYD’s abuses as justification for intervention.

In essence, the PYD’s tactics have played directly into Ankara’s narrative that PKK-affiliated elements endanger Turkish national security.

Externally, the PYD’s strategic opportunism has alienated Damascus’s transitional leadership. President Ahmed al-Sharaa and his Cabinet, forged from anti-Assad opposition ranks, recall how the PYD blocked ENKS envoys from meeting with Syria’s provisional ministers in 2012 and 2013.

They remember, too, how the PYD negotiated energy deals with remnants of the Assad security apparatus before seeking American support to fight Daesh.

Today, as these former rebels govern ministries such as Defense, Interior, and Local Administration, they view PYD demands for “full autonomy” as tantamount to separatism—an outcome they cannot accept without risking Syria’s fragile integrity.

The interim constitution ratified in March 2025 emphasizes national unity and merely affirms Kurdish citizenship rights, omitting explicit cultural or linguistic protections.

The PYD’s refusal to engage constructively with this framework signals its disinterest in genuine federal compromise and suggests a desire to perpetuate its quasi-state under any banner.

Moreover, international reliance on the PYD/SDF has skewed regional geopolitics.

The United States treated the SDF as its preferred ground partner against Daesh, overlooking the PYD’s direct ties to the PKK.

U.S. arms shipments bolstered PYD still further, even as the group used Western-provided equipment to crush ENKS-affiliated uprisings in towns like Raqqa.

France and Germany offered rhetorical support for “inclusive governance,” yet continued to coordinate exclusively with the PYD as the de facto authority in northeast Syria.

This Western posture has inadvertently validated PYD’s hegemonic ambitions and undermined the ENKS’s negotiating leverage in Damascus.

Meanwhile, the KDP under Masoud Barzani, eager to assert influence over Kurdish affairs across borders, funneled resources and political backing to the ENKS—but only insofar as ENKS remained complicit in PYD-dominated unity councils.

The KDP’s failure to advocate for genuine power sharing or hold the PYD accountable has effectively silenced moderate Kurdish voices.

Policy implications: Risks of continued PYD preeminence

Persistent engagement with the PYD as the sole Kurdish interlocutor ensures several negative outcomes. First, it perpetuates a cycle of authoritarianism that undermines the credibility of any “Kurdish administration” in the eyes of Damascus and Ankara.

When a group synonymous with a terrorist organization continues to operate with impunity, both the central Syrian government and neighboring states will view Kurdish governance as inherently illegitimate.

This perception has already provoked repeated Turkish incursions—operations labeled as “counterterrorism,” but which in practice displace civilians and wreck critical infrastructure.

As long as PYD holds sway, Damascus has little incentive to negotiate a lasting federal arrangement; why compromise with a faction that refuses to operate within the constitutional framework it helped establish?

Second, continuing to build Kurdish institutions around PYD/SDF reinforcement risks isolating moderate Kurds. Farmers, shopkeepers, and civil society leaders who oppose PYD’s repressive tactics have already grown silent or fled to KDP-held areas in Erbil.

As the PYD consolidates power, it diminishes any internal check on its authority, making long-term stability impossible.

The ENKS’s moderate base, which could provide the democratic underpinning for federalism, lacks access to international support or even basic security guarantees.

Without tangible alternatives, disillusioned Kurds may align with Damascus’s interim government or accept Turkish-backed governance structures to escape PYD’s rule.

Either scenario shatters the prospect of a unified Kurdish position in broader Syrian negotiations.

Third, the PYD’s refusal to release political prisoners, allow independent media, or engage in transparent governance severely constrains Western leverage.

When the U.S. and its allies tie military and reconstruction aid to “inclusive administration,” the PYD simply pays lip service, makes superficial gestures—releasing a token handful of detainees—and continues its hardline domestic policy.

This pattern has led to donor fatigue and skepticism about Kurdish partners. Should the United States pivot away from the PYD, Damascus could offer a partnership to the ENKS, effectively co-opting Kurds into a centralized state under Assad’s successor regime.

Western abandonment of the ENKS at this juncture would amount to a strategic defeat: the very entity that once bridged the Kurdish question with Syria’s broader opposition would be rendered irrelevant.

Recommended actions: Elevating ENKS for federal settlement

To break the impasse, the international community and regional actors must decisively shift policy.

First, the United States, European partners, and the KDP must announce that continued military aid and diplomatic recognition hinge on the PYD’s willingness to fully integrate into Syria’s constitutional process.

This means dissolving all Asayish checkpoints not approved by Damascus, releasing all political prisoners, and opening long-denied ENKS offices in AANES territory without security screenings or bureaucratic obstruction.

By publicly linking aid to these benchmarks, external actors send an unambiguous message: coercive governance will no longer be tolerated.

Second, the interim government in Damascus should grant the ENKS formal negotiating status, alongside an independent Kurdish delegation free from PYD dominance.

ENKS envoys must be invited to participate in constitutional committees and to propose specific guarantees: Kurdish language instruction in public schools across Hasakah and Qamishli, proportional representation for Kurdish-majority districts in the Syrian Parliament, and local security councils staffed by ENKS-affiliated community leaders under joint oversight with Damascus.

By engaging the ENKS directly, Sharaa’s administration cements its revolutionary credentials—demonstrating that it can accommodate minority demands—while reducing the PYD’s leverage as Damascus’s only Kurdish interlocutor.

Third, a phased security transition should be brokered under U.N. observance. Asayish and YPG forces must be rebranded into an “Eastern Syria Security Force,” integrating ENKS-aligned personnel and Syria’s regular army under a unified chain of command. International monitors would verify that no PKK-affiliated fighters remain in northeastern garrisons.

This arrangement addresses Ankara’s core concern—dismantling PKK footholds—any integration process must explicitly exclude former Ba’athist loyalists, particularly those with records of repression or ties to the old security apparatus.

Allowing such figures into Kurdish areas under the guise of national cohesion would not only provoke local backlash but could also reignite the very grievances that fueled the revolution.

A reconstituted Eastern Syria Security Force must be cleanly severed from both the PYD’s PKK-linked militias and the remnants of Assad’s mukhabarat state, ensuring that security structures reflect the values of the transitional order, not its oppressors.

Fourth, reconstruction funding and political aid should be reprogrammed to bolster ENKS-led local governance projects. Instead of channeling resources through AANES ministries controlled by the PYD, international donors should fund municipal infrastructure, civil society initiatives, and cross-border trade networks managed by ENKS-affiliated councils.

By redirecting financial incentives, the ENKS can rebuild legitimacy on the ground, offering real alternatives to the PYD’s patronage networks.

This shift also gives ordinary Kurds tangible reasons to support ENKS leadership while holding the PYD accountable for governing failures.

From 2011 to June 2025, the ENKS-PYD conflict in northeast Syria has sown fragmentation and undercut Kurdish aspirations.

The PYD’s authoritarian practices, rooted in PKK doctrine, have alienated Damascus’s new interim government and justified Turkish intervention. International reliance on the PYD/SDF has rewarded repression, marginalized moderate Kurdish voices, and squandered an opportunity for an inclusive federal settlement.

With former Assad opposition figures now entrenched in Damascus—eager to consolidate a post-war order—the time is ripe to recalibrate.

Elevating the ENKS as the legitimate Kurdish interlocutor will facilitate a constitutionally grounded federal compromise, one that defuses Türkiye’s security pretext and integrates Kurdish communities into Syria’s future.

Anything less risks perpetuating violence, undermining reconciliation, and forfeiting the fragile gains of the revolution.