El-Fashir was once the beating heart of North Darfur — a crossroads of markets, institutions, and memory.Today, it represents something different: a provincial capital that has experienced extended military pressure. For 18 months, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have encircled the city, transforming it from a provincial capital into a case study in modern warfare’s disregard for civilian life. UN figures indicate over 460 civilian deaths and mass burials, while the city’s fall reflects a broader reality — Sudan’s fragmentation into zones of militia power and humanitarian neglect.

Red-stained earth, captured in satellite images, bears witness to the side-by-side bodies of children. General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, widely known as Hemedti, presents himself as the “man who saved the country,” yet the silence on the ground tells a very different story. El-Fashir has become one of Sudan’s darkest historical repetitions.

The humanitarian crisis extends far beyond Darfur. U.N. humanitarian coordinator for South Sudan, Alain Noudehou Gbeho, has warned that approximately 9.3 million people across Sudan are in urgent need of aid, highlighting the scale of suffering affecting the country as a whole.

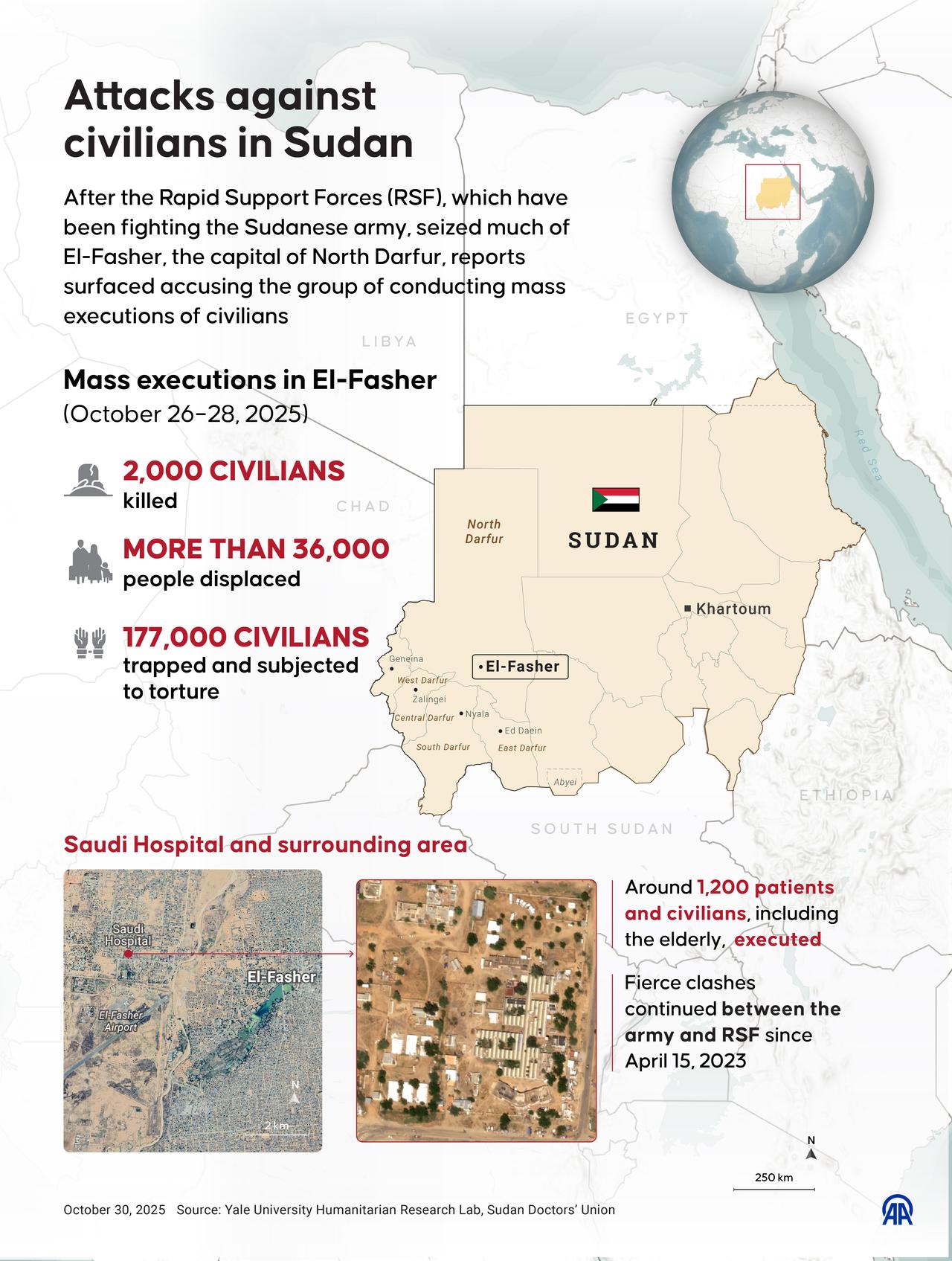

El-Fashir, the largest city in Darfur, fell under RSF control after an 18-month siege. Weekend clashes erupted violently, and by Sunday, the city was largely under RSF control. What followed went beyond warfare, taking on the form of a systematic massacre.

Satellite images reveal blood-soaked streets and mass graves. The World Health Organization confirmed that more than 460 patients and caregivers were killed at the Saudi Hospital alone. The Sudan Doctors’ Network reported that the RSF executed everyone they found there.

U.N. satellite reports document mass graves described as “clusters roughly the size of human bodies.” The red soil, visible even from space, reflects only a fraction of the horror. Survivors who escaped tell harrowing stories. Tacal Rahman, speaking to the Associated Press, summed up what he saw: “Everywhere has turned into a grave. Bodies are everywhere. People are wounded, but no one can help them.” These words encapsulate 18 months of silent suffering. Women have been subjected to sexual violence and killed; men have been executed under the pretext of ID checks; and children have perished from hunger and thirst.

Africa has long been a continent of wars, massacres, and genocides. While colonial-era atrocities are now documented in books and archives, today’s tragedies in Sudan, the Congo, and elsewhere are broadcast live to our screens. Yet little has changed. These crises often pass in a few superficial minutes on the news and vanish into social media algorithms. African humanitarian disasters struggle to find a place on the global agenda.

Sudan’s history stretches back to the Ottoman period. In 1820, Mehmed Ali Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Egypt, effectively brought Sudan under Ottoman control. A centralized administration was established in Khartoum, introducing modern governance in taxation, justice, and public order. By blending Islamic and modern law, the administration implemented land registries, property regulations, and court systems. Military training and discipline laid the foundations of organized state capacity in the region.

Yet geographic challenges, inter-tribal conflicts, and local resistance prevented lasting stability. By 1885, the Mahdi Revolt ended Ottoman-Egyptian rule, deepening Sudan’s central authority vacuum. The Anglo-Egyptian administration, which began in 1899, inherited these structures, but British colonial policies and local resistance limited their effectiveness.

In 1951, Egypt’s King Farouk declared himself “King of Egypt and Sudan,” a symbolic move with no recognition. After Farouk’s overthrow in 1952, General Muhammad Naguib pressed for Sudan’s independence, achieved on Jan. 1, 1956.

Post-independence Sudan faced 35 military coups, North-South civil wars, and ethnic conflicts in Darfur, all of which exposed the state’s inability to protect its people. North-South wars lasted decades; Darfur’s violence has claimed more than 300,000 lives since 2003, displacing millions. During Omar al-Bashir’s rule, militias organized under the Janjaweed committed ethnic cleansing against African tribes, later labeled genocide by the U.N.

The 2011 secession of South Sudan deprived Sudan of resources and triggered new power struggles. In 2013, former Janjaweed members formed the RSF, laying the groundwork for future internal conflicts. After Bashir’s ouster in 2019, General Abdelfattah al-Burhan and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo established the Sovereignty Council. But competition between the generals soon plunged the country into a new disaster.

Sudan’s current conflict is not merely a struggle between two generals. It is part of a long history of proxy wars fought over gold, land, and geopolitical advantage. The RSF receives backing from the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and covert support from Israel. Gold mines under RSF control feed clandestine supply chains to the UAE; Russian Wagner mercenaries operate on the ground; Chinese-made guided bombs reach the RSF through the UAE.

British weapons help sustain this global proxy war. The blood of Sudan’s citizens has become the sole shared currency of these shadow alliances.

The siege of El-Fashir lasted 18 months, devastating the city’s infrastructure. Hospitals were destroyed, water supplies depleted, and farmland burned. Over 6,000 children are at risk of malnutrition, according to the U.N. After Sudan’s army withdrew under the pretext of protecting civilians, El-Fashir effectively fell to the RSF. Today, all five Darfur state capitals are under RSF control, leaving the country on the brink of de facto division. RSF militias shout “Kill the Nuba!” while systematically slaughtering fleeing civilians. Though both sides invoke the same God, what is happening is ethnic cleansing at its most extreme.

Women and children bear the heaviest toll. Reports by Amnesty International and UNICEF document the RSF’s crimes against women and girls, including rape, gang rape, and sexual slavery. UNICEF reports that in 2024 alone, 221 cases of child rape were recorded, including 16 victims under five and four infants aged only one. Sexual violence is wielded as a weapon; victims face social stigma, suicide risk, lack of medical care, and the absence of safe spaces.

For over two years, Sudanese civilians have struggled to survive amid escalating slaughter. Since fighting broke out on April 15, 2023, over 100,000 innocent lives have been lost, and more than 14 million people have been displaced. Schools are closed, agriculture has stalled, and 80% of healthcare infrastructure has collapsed.

Hunger, disease, and lack of medicine have spread across the country. The U.N. calls the humanitarian situation “a complete disaster” and urges urgent international intervention.

Sudan’s fertile lands and strategic position make the global indifference even more troubling. The confluence of the White and Blue Nile creates rich farmland, while Sudan’s production of Arab gum attracts global attention. Sudan is Africa’s third-largest gold producer, with rare minerals vital for global industries. Agriculture, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals rely on these resources, proving the war is fought not just locally, but for global interests.

The Sudan Doctors’ Network confirmed over 460 deaths at the Saudi Hospital alone, and satellite imagery exposes mass graves in the red earth. Hemedti’s promised investigations do nothing to alter reality. As Sudanese nurses put it: “We are not afraid of dying; we are afraid of being forgotten.”

The international community remains largely silent, though Türkiye, the EU, Saudi Arabia, and others condemned the attacks. In the U.S., both Democratic and Republican senators called for the RSF to be designated a foreign terrorist organization; former U.S. President Joe Biden recognized the RSF as committing genocide and placed Hemedti on sanctions lists.

But these symbolic gestures change nothing on the ground. Sudan’s tragedy exposes not just a nation’s failure but the failure of the international system. Twenty years ago, Darfur’s crimes were labeled genocide; today, similar atrocities are repeated while the world remains silent.

The silence surrounding Sudan is a test of humanity itself. In Africa’s fertile lands, innocent populations are slaughtered for the interests of global powers, and the greatest crime of the modern era is this very silence. Our numbed consciences lay the groundwork for normalizing atrocity. What is happening to the people of Sudan is not merely a regional crisis—it is a crime against the conscience of humanity.