The Zangezur Corridor is seen by Türkiye as a multi-purpose transportation route that will connect the country not only to the Caspian Sea via the Caucasus but also directly to the broader Turkic world. Ankara continues to support the project both economically and diplomatically.

Türkiye’s Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan stated at a joint press conference in Al Alamein, Egypt, that “The Zangezur Corridor will be a key part of a seamless transportation network extending from Europe deep into Asia.”

Azerbaijan fully supports the corridor, with Presidential Foreign Policy Advisor Hikmet Hajiyev backing the project unequivocally. However, the success of the agreement depends heavily on political will and the concrete actions of all parties, especially Armenia. Agil Alesger, journalist, head of Azerbaijan’s Yeni Cag Media Group, and a board member of the Azerbaijan Press Council, underscored the complexity of the peace process and the fragility of the agreement in an interview with Türkiye Today.

Alesger elaborated extensively on the challenges and hopes tied to the corridor: “Peace agreements are crucial milestones in resolving long-standing regional conflicts, but their durability depends on many variables. It’s not enough for the document to be signed; genuine implementation, backed by both domestic political consensus and international support, is essential. Whether Armenia will fully relinquish its claims on Nagorno-Karabakh remains uncertain and depends largely on internal power dynamics.”

“This agreement poses a real threat to political factions in Armenia that have profited from perpetuating the conflict. Much like the OSCE Minsk Group, these entrenched interests could fade into history if constitutional reforms proceed and the agreement’s terms are honored,” he added.

Alesger also highlighted the importance of external influences: “There is significant opposition to Prime Minister (Nikol) Pashinian within Armenia, and the U.S. involvement partly aims to bolster his position against this resistance. A strong and stable Pashinian is critical for the peace process to move forward.”

Regarding regional tensions, particularly Iran’s stance, Alesger offered a nuanced and detailed perspective: “Iran’s harsh opposition to the Zangezur Corridor must be understood in the context of its domestic politics, regional power balances, and especially its security concerns. Tehran perceives the corridor as an expansion of Türkiye’s influence, which it views as a direct challenge to its national security interests.”

He explained, “While the U.S. or Israel may be portrayed as scapegoats for Iran’s concerns, the real apprehension is about Türkiye’s growing regional role. Within Iran itself, opinions are split—some officials like Pezeshkian and elements of the Foreign Ministry advocate a cautious approach, whereas hardliners loyal to the Supreme Leader take a much more confrontational stance.”

On the broader implications of the corridor, Alesger stressed its significance for the Turkic world: “Opening this corridor will provide Türkiye with a stronger land connection to the Turkic world, shifting the balance of power in the region. It’s an essential step toward enhanced economic cooperation, increased Turkish influence, and deeper regional integration.”

He continued, “This connection will enable Türkiye to develop a more integrated policy within the Turkic World. It can strengthen Türkiye’s solidarity with Turkic republics in the region and lead to expanded trade routes, increased economic collaboration, and greater cultural exchanges.”

Alesger also touched on the historical and political bonds between Türkiye and Azerbaijan: “The architect of the Karabakh victory is undoubtedly Ilham Aliyev, but his greatest political and moral support has come from Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The historical ties and brotherhood between our nations make Türkiye’s backing vital—not only bolstering Azerbaijan’s national interests but also contributing significantly to regional security and diplomacy.”

He noted the cautious optimism among the Azerbaijani public regarding peace: “While the Azerbaijani public views the constitutional changes regarding Karabakh in Armenia as removing obstacles to peace, they follow the process carefully. Influenced by historical experience, they approach the peace process with guarded hope. Achieving peace is a great hope for everyone in the region, but it’s understood that more concrete steps are necessary for this hope to last.”

He concluded, “We have regained our lands and want lasting peace in the region. For that, Armenia must take concrete steps. Although, as the victorious side, we have the right to demand compensation and other sanctions, we choose lasting peace.”

From the Armenian side, Turkish-Armenian journalist Yetvart Danzikyan, editor-in-chief of Agos newspaper, offered insights: “The Armenian public, especially those living in Türkiye, generally view the peace process positively. Many are quite satisfied with Prime Minister Pashinian’s approach to reconciliation.”

On the prospect of reopening the land border between Türkiye and Armenia, Danzikyan observed: “There is a hopeful outlook. Should the border open, it could foster meaningful, positive interactions between the two peoples, helping to break down long-standing prejudices.”

Regarding constitutional concerns raised by President Aliyev about Armenia’s stance on Nagorno-Karabakh, Danzikyan emphasized: “While Aliyev has expressed reservations about Armenia’s constitution, Armenians are urging Azerbaijan to adopt a more flexible approach to constitutional reforms. Importantly, international agreements take precedence over national constitutions, and Azerbaijan should avoid rigid insistence on this constitutional matter.”

He also remarked on the Türkiye-Armenia normalization efforts: “Türkiye is also imposing preconditions in this process. Thus, responsibility lies with both sides to move forward constructively.”

Taken together, these expert opinions paint a complex picture: while there is cautious optimism that the Zangezur Corridor and associated peace initiatives could reshape the Caucasus’ future, significant challenges remain. The interplay of internal politics, regional rivalries, and great power interests will determine whether this corridor becomes a conduit for lasting peace or another flashpoint in an already volatile region.

Associate Professor Serhan Afacan, chair of the Iran Studies Center (IRAM), a leading expert on the region, believes understanding the Armenia-Azerbaijan dynamic requires stepping back from Middle Eastern frameworks.

“Iran has historically taken a position aimed at preserving the status quo along the Armenia-Azerbaijan front,” he said. “During the Second Karabakh War, it maintained this stance. So, in essence, Iran did not have a fixed policy advocating immediate territorial changes—its consistent message was that borders must not be altered.”

From Türkiye’s perspective, there was no violation of Armenia’s sovereignty in the corridor project, and this was communicated to Tehran. Iran, however, saw the issue through its own lens: a small but critical 44-kilometer stretch of border with Armenia.

“Iran enjoys some of its best regional relations with Armenia—complex ties that include education, healthcare, and economic cooperation,” Afacan explained. “From Tehran’s point of view, any disruption to this border could harm these ties, and that was something they were determined to avoid.”

The second—and in some ways more sensitive—concern for Iran is what it calls the “Turan Corridor,” a term used in Tehran to describe the strategic linkage between Türkiye and the Central Asian republics, with the Zangezur Corridor at its heart.

“Iran fears this route could significantly increase Türkiye’s regional presence and bypass Iran’s traditional role as a transit corridor to Central Asia,” Afacan noted. “The alternative route via Iran has long been Türkiye’s option, and losing that role is a real concern for Tehran.”

Despite these concerns, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian recently struck a softer tone, saying there was no need for alarm and that such matters could be resolved through dialogue. “He made it clear there is no reason for Iran’s ties with Armenia and Azerbaijan to deteriorate over this issue,” Afacan said.

From the outset, Türkiye and Azerbaijan—alongside Armenia—have taken Iran’s concerns into account, even those they found less compelling. Afacan pointed out that Iran and Armenia’s close relations were reaffirmed immediately after the latest agreement, with a phone call between Pashinian and Pezeshkian. In that call, Pashinian reportedly assured him that “we will never be part of anything that harms your geopolitical interests.”

Afacan drew attention to a broader pattern: “After the Second Karabakh War, President Erdogan proposed the 3+3 format—a platform bringing together Türkiye, Iran, and Russia on one side, and Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia on the other. The idea was to manage the process regionally, unlike the Minsk format, and to focus on shared interests.”

Tensions, however, were not absent. Iranian media and politicians at times issued sharp criticism—sometimes even unfounded accusations—against Türkiye. “This stemmed from three main factors,” Afacan explained. “First, the change in the status quo itself; second, Iran’s claim that Israel played an active role in this process; and third, the perception that Türkiye would become more dominant in the South Caucasus.”

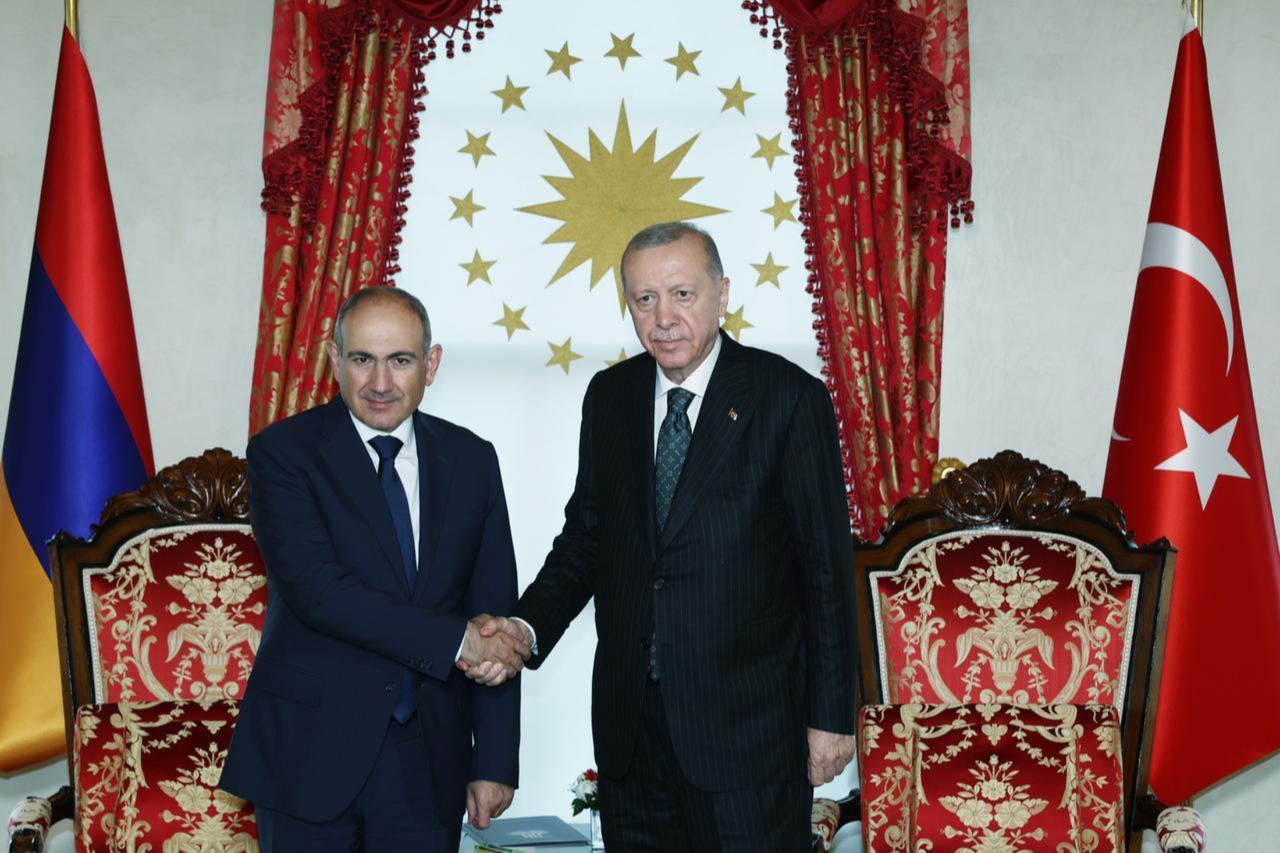

Over time, Tehran’s tone began to shift, a change Afacan attributes largely to Pashinian’s diplomacy. “He met frequently with both President Erdogan and President Ilham Aliyev. Just weeks ago, he held a five-hour meeting with Aliyev in Abu Dhabi. In Istanbul, at a meeting with the Armenian community, Pashinian even downplayed the ‘Turan Corridor’ fears, saying, ‘So what if there’s a Turan Corridor? Let them build it; it will benefit us.’”

Afacan emphasized that if Armenia itself accepts the corridor, Iran’s argument that it violates Armenian sovereignty loses weight. “Tehran has recognized this reality,” he said. “And with recent internal debates in Iran—especially after the conflict involving Israel—there is a growing push for more open, cooperative regional policies.”

Pezeshkian has also publicly questioned the rationale for tensions with Baku, asking, “What has Azerbaijan done to us?” and suggesting that corridors in the region could be beneficial to all. Afacan believes this signals a more pragmatic Iranian stance: “From here on, unless new problems emerge between Azerbaijan and Armenia, Iran is unlikely to obstruct this process—it lacks both the right and the capacity to do so. More likely, Tehran will seek to link itself to the project in ways that make strategic sense, even if that means engaging with platforms like the Organization of Turkic States, which it has so far kept at arm’s length.”

The implication, Afacan concluded, is that the Zangezur Corridor could move forward with Iran’s cautious tolerance, rather than its outright resistance. This development could significantly ease the path toward a more integrated and less volatile South Caucasus.

Cultural diplomacy plays a vital role in shaping state-to-state relations and fostering long-term peace. Tugce Tecimer, an analyst at the Eurasia Studies Center and historian (AVIM), emphasizes that Turkish-Armenian relations must be understood within their historical context to comprehend the current Armenia-Azerbaijan peace process. “This legacy is not only diplomatic but still deeply affects societies,” she says, highlighting the lasting impact of the 1915 Deportation and Resettlement Law.

The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War’s outcome pushed Armenia to rethink its ties with Türkiye and Azerbaijan. Tecimer explains, “Azerbaijan’s victory imposed a new geopolitical reality on Armenia, prompting shifts in its foreign policy.”

Eastern Anatolia symbolizes national unity and security for Türkiye, but represents the idealized “Western Armenia” for Armenia. The South Caucasus, meanwhile, is a key regional hub for energy and transport, at the center of power struggles.

“Unresolved historical issues remain a major barrier to lasting peace,” Tecimer notes, urging Armenia to “shed dogmatic beliefs, question unfounded genocide claims, and overcome past traumas to open a new chapter.” She views Pashinian’s efforts as generally positive despite some inconsistencies.

Cultural exchange plays a critical role in building trust. Tecimer states, “Understanding each other’s language, history, and arts helps break down prejudices and supports peace beyond diplomacy.” She points out that changing Armenia’s constitution—a key demand from Azerbaijan—is crucial, as “it shapes societal attitudes toward peace.” She also warns that hostile themes in Armenian literature harm reconciliation, citing attempts to legitimize terrorism against Turkey, which fueled militant groups like ASALA.

On regional identities and politics, Tecimer stresses, “The South Caucasus attracts international interest, but lasting peace depends on local actors’ commitment.” She cautions that foreign interference often stalls progress, emphasizing that peace must be achieved through regional consensus.