Armed drones have moved from niche assets to widely traded weapons, yet their impact on African battlefields remains constrained. Drawing on research by Associate Professor Brendon J. Cannon of Khalifa University, recent conflicts show that drones can kill and surveil, but they rarely deliver outright victory in sub-Saharan Africa.

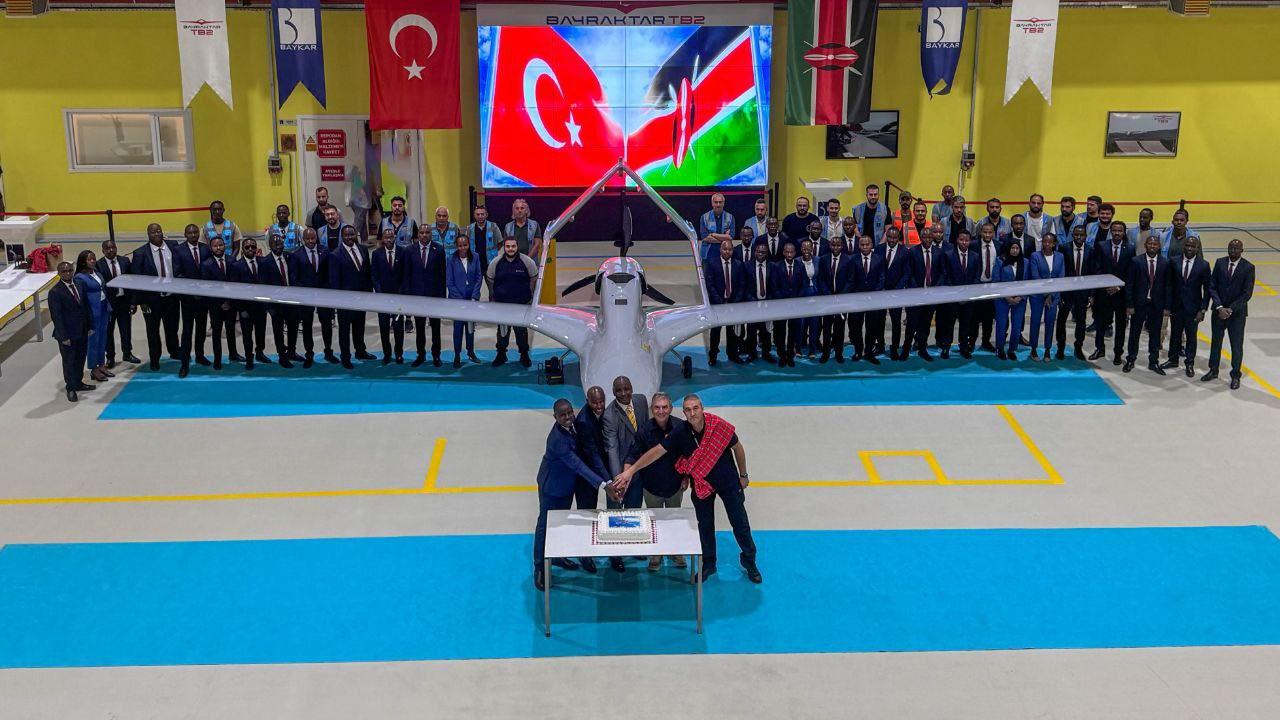

Türkiye’s Bayraktar family—the TB2, its ship-capable successor TB3, and the jet-powered Kizilelma—sits at the center of this debate.

Governments facing terrorist incursions, insurgencies, and civil wars see drones as agile, affordable tools. Since 2019, countries including Niger, Ethiopia, Togo, Sudan, and Somalia have acquired medium-altitude long-endurance (MALE) systems—drones that typically fly for many hours at medium altitude to provide persistent surveillance and precision strike.

The TB2 has drawn outsized attention for reliability and availability. Some sources estimate that around 40 TB2 units have gone to more than 10 African countries since 2019, though exact figures are not public. At roughly $5 million per unit, leaders were impressed by performance in earlier wars and by visibility on export markets. As President Recep Tayyip Erdogan put it: “Everywhere I go in Africa, everyone talks to me about drones.”

Cannon’s work underscores how distance, basing, and communications limit results. The TB2’s approximately 300-kilometer range can be effective in compact theaters, but Africa’s vast spaces demand forward bases, relay links, and ground infrastructure to sustain coverage.

In Ethiopia in 2022, TB2s were repositioned from near Addis Ababa to Bahir Dar—roughly 300 km—to reach targets in Tigray, illustrating how basing drives outcomes.

Dust and sandstorms in the Sahel degrade visible-light sensors; dense forests and persistent cloud cover in central and eastern regions cut detection and tracking.

Electro-optical and infrared payloads widen the envelope, but drones may still need to fly below weather systems, raising exposure to ground fire—as seen in Sudan, where paramilitary forces reported downing army drones in August 2025.

Effectiveness hinges on trained crews, disciplined targeting, and dependable maintenance. A Burkinabe TB2 crash in 2023 highlighted operational fragility.

Drones excel at hitting supply convoys, striking small groups, and targeting specific individuals in low-intensity warfare.

They are far less decisive in holding territory or confronting massed formations, tasks that still depend on fighter-bombers, attack aircraft, and ground forces—a pattern visible in recent wars in Ethiopia and Sudan.

Cannon notes that as non-state groups field more drones and as states such as Rwanda and Kenya deploy better air defenses, the advantage enjoyed by governments with drones will shrink. Sustained utility will require more than procurement.

Cannon’s assessment points to three priorities: